One of the hallmarks of many “nondenominational” denominations within the United States and Great Britain is the eschewing of any manner of distinctive clerical uniform or vesture when ordained ministers lead Christian worship. The rationale behind these abstentions is that such clothing sets the minister “apart from the people,” smacking of clericalism, unduly calling attention to the separateness of the minister, his authority, etc., etc., and that to be one with the people the minister should (perhaps “must”) dress as “one of the people.”

However, when I have visited churches that have such a mindset, sometimes the emphasis on being “one of the people” can go unintentionally awry: In some instances, the middle-aged minister will be wearing clothing so contemporary and “hip” that they appear as genuine as my trying to use the word “hip”…or the phrase “with-it,” like a father trying to use the teenage lingo of his offspring. In other instances, the minister’s attempt to “dress down,” could almost be seen as disrespectful (t-shirts, floral short sleeves, etc). Perhaps the worst variation on this theme is the minister who wants to “not dress like a minister” but still appear somewhat “dressy” or formal, wearing clothing so expensive and ostentatious that you’re left wondering if the church may be paying the man too much, or if he realizes what an affront such clothing could be to the poorer members of the congregation.

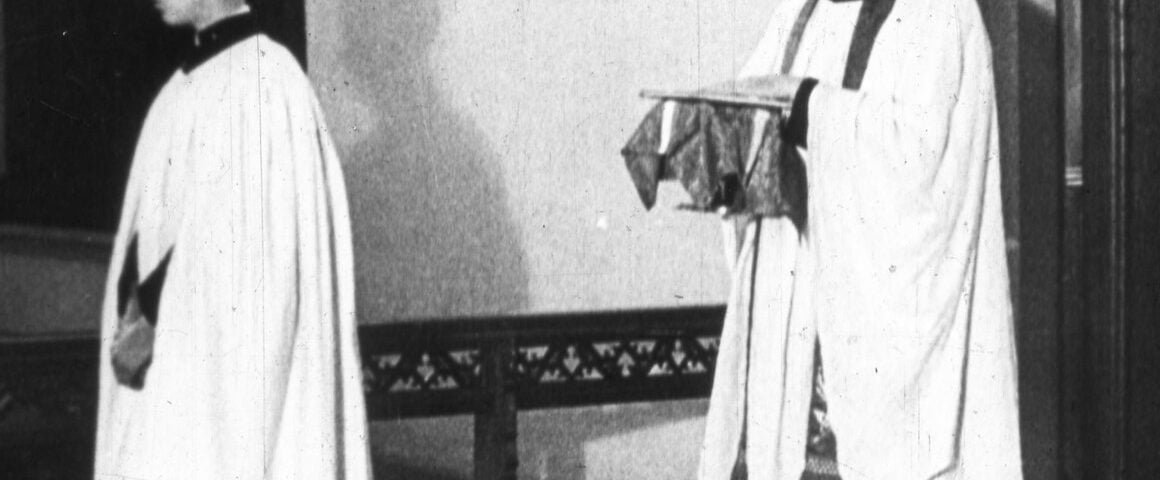

You’ll notice that the pictures used to illustrate this entry have come from what is now seen as the “evangelical” tradition of the Anglican spectrum (what was, for several hundred years, the basic vesture of Anglican priests)–the classic cassock, surplice, and tippet still worn as the standard by clergy of the Free Church of England. In parishes and cathedrals in the United States and the United Kingdom that follow Percy Dearmer’s scholarly admonitions, the surplice and tippet are worn for Morning and Evening Prayer, while an alb, stole, and chasuble are worn for the Holy Communion; in some parishes, the surplice and tippet are still retained for Communion, whereas in others a stole is worn over the surplice–in still other places the cope may be worn over the surplice and stole or tippet.

While there is variety in such practices, it is still quite clear that the priest is, well, the priest. You could swap out Vicar Smith for Father James or Dr. Williams and you could still tell who was the ministerial presence leading the divine worship of the Church, for he would be wearing a uniform clearly recognizable as that of an ordained minister of the Church. The priest doesn’t represent himself, he represents the office of the Church, and the Church as an extension of Christ’s presence–and he holds this as a temporary cell in the Body of Christ: People are coming to the ministry of the Church for the ministry of Christ, not the ministry of the man who holds the office. When the priest leaves, retires, or dies, another will take his place to perform the same preaching, sacramental, and ministerial functions, and what this new priest does and how they are known as the holder of the office of the parish priest is not a place primarily for the expression of individualism–the Eucharist should remain substantially the same (which is why the use of the historic rites is also paramount), the Baptismal rite should remain the same, the preaching should remain doctrinally the same. The office of the priest carrying out these functions should display continuity with what has come before, not just recently, but reaching back in time to previous ages.

When the priest wears at the very minimum the cassock and the surplice, he identifies himself with the office of the historic priesthood to carry out his Christ-like sacramental care of God’s people, to demonstrate God’s presence in the world. The uniform of the priest constrains the priest in a way similar to the liturgy of the Prayer Book constraining the priest: What the priest preaches from the pulpit must (or should) conform to the doctrine of the Prayer Book, for the language of the Prayer Book verbally exemplifies the continuity of the Church Catholic. Similarly, if he dons the cope or the chasuble for the celebration of the Holy Eucharist (as they both descend from the same garment), he is identifying with the continuity of the ancient Church in the celebration of this Sacrament. What he does at the Holy Table is the same as what Lancelot Andrewes did, what Saint Augustine of Canterbury did, what Saint David did. When the people look to the priest, they should see not only themselves as humans (and the faults, frailties, and failings of the individual minister), but the work of Christ in His world through His Church. This is why, whether an ordained priest is an “evangelical” or “Anglo-Catholic,” or an “evangelical Anglo-Catholic,” that priest should be identifiable as a priest of Christ’s historic Catholic Church, so that when the faithful see him, they see not only him, but a local expression of the universal Body of Christ that reaches both forward and backward in time.

'Vestments Matter' has 1 comment

April 30, 2022 @ 12:06 pm The Rt Rev'd H. L. Poteet

Strangely this article fails to mention the Ornaments Rubric of 1662 or its predecessor in 1559 Nor does it mention “The Preface” of 1789 that was then included in every American BCP through 1928. 1662 requires the pre reformation vestments, i, e., even if the Church was unable to restore them for fear of another repeat of Cromwell and friends.