OR…If Anglicans don’t have priests, nobody does

Archbishop Frederick Temple is not known as an original theologian or scholar. In fact, Frederick Temple is probably best known as the father of a future Archbishop of Canterbury, William Temple. However, one extremely important event occurred in 1896 while Frederick was Primate of all England: The Church of Rome, in the person of Pope Leo XIII in his bull (and what bull it was) Apostolicae Curae, declared the Holy Orders of Anglicanism–the Orders that had been bestowed upon the likes of Lancelot Andrewes, William Laud, Samuel Seabury, and John Wesley–“utterly null and void.” This declaration was based upon the assumption that the revised Ordinal prepared by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer in 1549 was significantly defective.

One of the major objections made to the Anglican Ordinal was that the language used was insufficient in the making of bishops. The words of the Anglican Consecration rite were “Take ye the Holy Ghost, and remember that thou stir up the grace of God, which is in thee by imposition of hands” while the Roman Pontifical simply states “receive the Holy Ghost.” If Anglican bishops are not to be accounted as properly raised to the episcopate, neither then are the bishops of the Roman Catholic Church by the same standard so applied. Indeed, all of the bishops and archbishops of the Roman Church have just been laymen…if we use the logic of Rome: Thank God we don’t.

Pope Leo XIII also objected that the Anglican priests were not instructed by the Ordinal to offer the Mass for the quick and the dead; instead, they are told to preach the Word and administer the Sacraments. As the instruction pertaining to the Sacrifice of the Mass was only added to the Roman Ordinal in the 11th Century, again it must be stated that if Anglican priests are not properly priests then neither were any of the presbyters of Western Christendom: There never have been any Christian priests, because the rite for making such priests (according to Roman standards) didn’t exist for the first thousand years of Christianity. The great sees of ancient Christendom never had any priests celebrating the Eucharist, nor did they have any bishops making priests…if we use the logic of Rome. If Rome were held to its own standard, the Catholic Church didn’t exist for the first 1000 years of the Catholic Church.

Other spurious arguments were made by various Roman authorities against Anglican Orders, much of the same caliber as those already mentioned. Some of the arguments pertained to the vestments worn or posture taken by the priest during Holy Communion (keeping in mind that vestments had also changed over a millennium of practice—and that the cope and the chasuble emerged from the same garment). One other objection was that Anglicanism itself lacked a full understanding of the Eucharist as sacrifice. Indeed, the Church of England had rejected, both in her liturgy and in the 39 Articles, the notion that each Mass offered Christ as a new Sacrifice to the Father. Instead, in its liturgical theology it chose to emphasize the teaching of Saint Augustine of Hippo:

If you wish to understand the body of Christ, listen to the words of the Apostle: “You are the body and the members of Christ.” If you are the body and the members of Christ, it is your mystery which is placed on the Lord’s Table; it is your mystery you receive. It is to that which you are to answer “Amen,” and by that response you make your assent. You hear the words “the body of Christ,” you answer “Amen.” Be a member of Christ, so that the “Amen” may be true.

This sentiment is echoed in Cranmer’s Prayer of Oblation (which follows the reception of the Bread and Cup in the English Rite, which is liturgically an excellent place for it, for we have just received the Body and Blood of Christ):

O LORD and heavenly Father, we thy humble servants entirely desire thy fatherly goodness mercifully to accept this our sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving; most humbly beseeching thee to grant, that by the merits and death of thy Son Jesus Christ, and through faith in his blood, we and all thy whole Church may obtain remission of our sins, and all other benefits of his passion. And here we offer and present unto thee, O Lord, ourselves, our souls and bodies, to be a reasonable, holy, and lively sacrifice unto thee; humbly beseeching thee, that all we, who are partakers of this holy Communion, may be fulfilled with thy grace and heavenly benediction. And although we be unworthy, through our manifold sins, to offer unto thee any sacrifice, yet we beseech thee to accept this our bounden duty and service; not weighing our merits, but pardoning our offences, through Jesus Christ our Lord; by whom, and with whom, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, all honour and glory be unto thee, O Father Almighty, world without end. Amen.

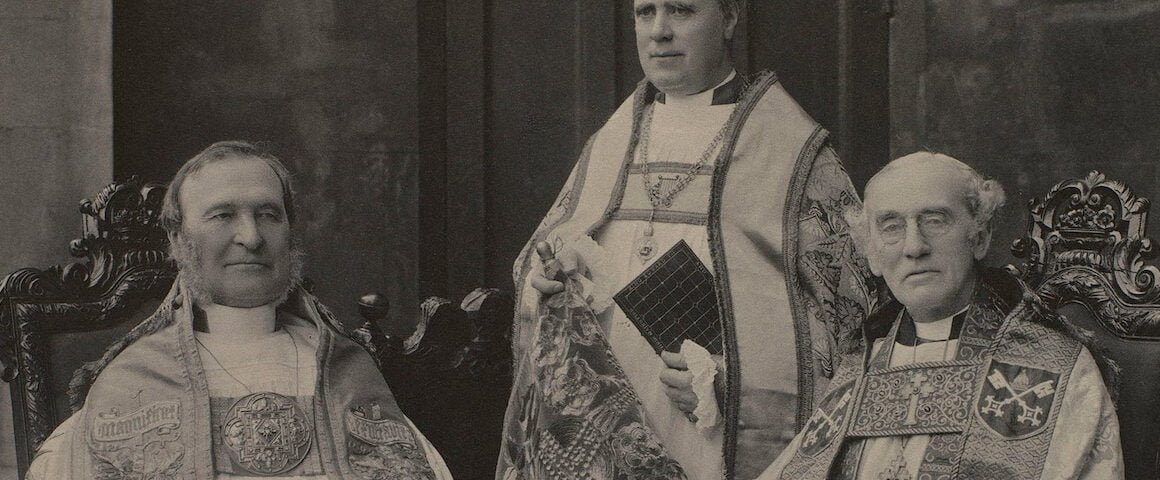

This is the Eucharistic theology prayed through the Anglican liturgy. When Frederick Temple, as Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Archbishop of York responded to Leo concerning this important issue, they did so via a letter directed to “the whole body of Bishops of the Catholic Church.”

We make provision with the greatest reverence for the consecration of the holy eucharist, and commit it only to properly ordained priests and to no other ministers of the church. Further, we truly teach the doctrine of eucharistic sacrifice, and do not believe it to be “a bare commemoration of the sacrifice of the cross,” an opinion which seems to be attributed to us (by Roman Catholics). But we think it sufficient in the liturgy which we use in celebrating the holy eucharist–while lifting up our hearts to the Lord, and when now consecrating the gifts already offered that they may become to us the Body and Blood of the Lord Jesus Christ–to signify the sacrifice which is offered at the point of the service in such terms as these. . . .[F]irst we offer the sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving; then next we plead and represent before the Father the sacrifice of the cross, and by it we confidently entreat remission of sins and all other benefits of the Lord’s passion for all the whole church; and lastly we offer the sacrifice of ourselves to the creator of all things which we have already signified by the oblations of his creatures. The whole action, in which the people has necessarily to take part, we are accustomed to call the eucharistic sacrifice.

This is the eucharistic theology of St. Augustine, enshrined in The Book of Common Prayer and taught by the orthodox Anglican divines of the Reformation and Restoration. It is the faith we hold today—as members of the Catholic Church.

'Holy Orders Within Anglicanism' have 4 comments

March 14, 2022 @ 11:37 am +Lee Poteet

At the moment I am rerrading Lacey’s “ARoman Diary” which concerns the bull, which was certainly not the pope’s work and was probably written in England. Lacey’s Latin is certainly better than that of the bull as is his reasoning and scholarship. But the best way of proving our true catholicity (to which I am committed) is to drop all imitation of Rome and live up to the historic prayerbooks beginning with that of 1559. That would require we embrace our own liturgical past in the Use of Sarum to which the rubrics of both 1559 and 1662 point.

March 15, 2022 @ 6:02 am Fr. Tommy Allen

The oblation quote is not properly quoted FYI.

March 15, 2022 @ 10:01 pm Rev. Dr. Derrick Hassert

Thank you for pointing out the error (not sure how or why I’d truncated it); the fullness of the prayer illustrates the theology much better.

July 6, 2024 @ 11:36 pm Mack

The Catholic complaint is that Edward 6\’s revised 1552 ordinal says, “Take the Holy Ghost“ but doesn\’t in that sentence say precisely for what office such as bishop, or priest, or deacon, etc., and this vagueness is allegedly fata. In 1662 words identifying the office as \”bishop\” were added, but the Catholics claim that it was too by then to cure the problem due to lapse. Their argument assumes that no where else in the ordinal service is the intent of ordaining a bishop made perfectly clear. Yet \”bishop\” is mentioned throughout, including prayer that God would \”mercifully beholde this thy servaunt, now called to the worke and ministerie of a Bisshoppe,\” and right the imposition of hands he\’s given a bible and told \”bee to the flocke of Christ a shepeheard, not a wolfe\” etc. So in reality the intent between 1552-1662 was perfectly clear and the catholic objections are frivolous.