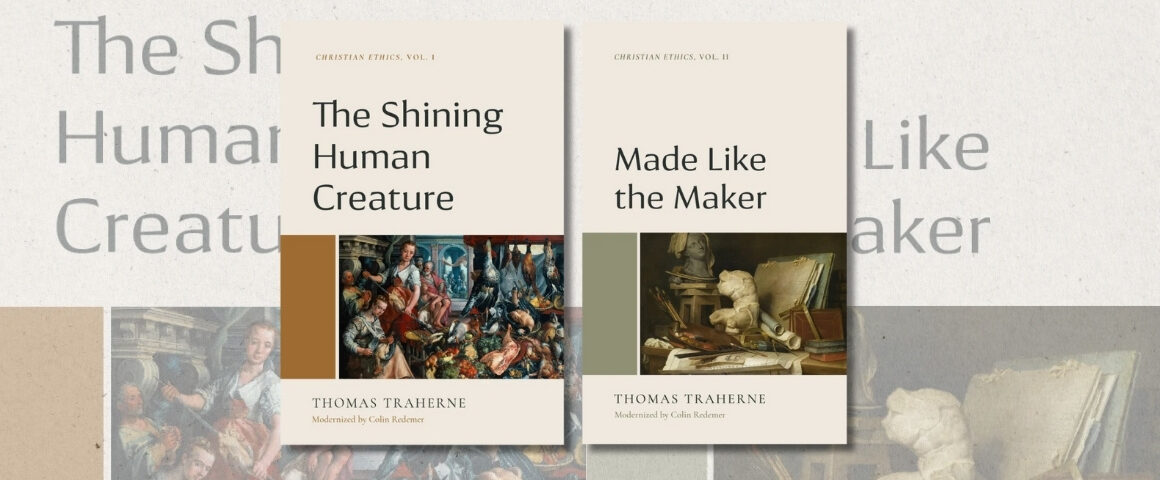

The Shining Human Creature and Made Like the Maker. By Thomas Traherne. Modernized by Colin Redemer. The Davenant Institute, 2023. 133 pp and 140 pp. $17.95 each (paper).

Thomas Traherne has one of those names that just sounds like he was born as an Oxford poet in a quaint, misty English village. In this case, that association has merit. He was a poet-priest during his short life, though his Centuries and Poetical Works, now his chief claimants to fame, weren’t even discovered until two centuries after his death in murky circumstances. His Ethicks, published right after his death, fell into instant obscurity.[1]

This crime has only recently been amended. Colin Redemer, professor at St. Mary’s College of California and Director of Education at American Reformer, recently republished the first half of the Ethicks in two volumes: The Shining Human Creature and Made Like the Maker, modernizing young Traherne’s beautiful magnum opus into two invitingly slender volumes.

Beyond the reasons Dr. Redemer gives in the introduction, Traherne is valuable reading because it puts us in a time we are not as historically familiar with, particularly as 21st-century Anglicans. He wrote at a time when Reformed Orthodoxy, the school of thought adopted by the anti-Episcopal church which first ordained him in 1656, had grown stale and prone to schism. Seeing its shortcomings up close, he accepted re-ordination into the newly re-established Church of England upon its reestablishment, and returned to a humanism that he thought animated the first generation of Reformers. His only published work before his death being a scathing account of Rome’s forged claims to authority, Traherne in his Ethicks avoids much of the systemization that accompanied the earlier Westminster Standards and ethical casuistry used by Caroline Divines and nonconforming Puritans alike, preferring a thoroughly transcendent, yet emphatically moral and humanistic account of the Good Life. If Traherne himself was forgotten, his Ethicks provides a golden glimpse into the new way of being Christian that was born in the wake of the 1662 Prayerbook and would dominate England and America until the Evangelical Awakenings in the late 1700s.

It is in Traherne’s Ethicks, for instance, that the reader can clearly see the ethical code and worldview of George Washington (b.1732) come to life, and fit within a broader orthodox Christian framework. And this is another part of the significance of both The Shining Human Creature and Made Like the Maker. They give a glimpse into a way of doing Anglican—indeed, Protestant—theology and ethics that moves beyond the theological polemics of the Reformation era, and avoids the Evangelical platitudes that have caused more than a few ambitious Protestants to disembark for greener pastures or higher ceilings. In Traherne a worldview is laid out, which if it cannot be entirely reentered into, can certainly be plundered to revive our Republic and our Province.

Traherne’s genius is in using classical Aristotelian means of reasoning, but doing so with a willingness to deviate from the medieval tradition in a number of respects. Modern Evangelical readers will rejoice in his interpolation of Biblical commands like Repentance and Mercy into the classical virtues, a willingness to modify the Great Tradition he shares with his contemporary Jeremy Taylor’s Doctor Dubitantium.[2] Furthermore, being on the cusp of the modern era, he sublimely blends his reflections on the virtues with a higher view of man’s integrity and faculties than would the medieval schoolmen.[3] Traherne delivers this humanism through some creative social trinitarianism which might leave the reader with a cocked eyebrow. But Traherne believes this judicious weaving of trinitarian life into virtue ethics is possible because the human form, and creation itself, reveal God’s trinitarian glory and gospel.[4] In this he is centuries ahead of his time, and if unorthodox, unorthodox in the right direction.

Action is of utmost importance for Traherne, and it’s a distinguishing feature of his Ethicks. The man who does not act is pitiable, but the man who acts poorly is humiliated.[5] Right action therefore becomes the necessary quality of man for the pursuit of virtue and the elimination of idleness (the enemy of virtue).

Without right action, man is strikingly powerful, but he lacks legitimacy, or in Traherne’s usage, clothing. “Every power of the soul is naked, without the quality by which long custom clothes it.”[6] Man is powerful, but virtue gives him glory.

Virtue isn’t pursued for personal glory however. Man’s power is an insufficient image of God, and will end in his own grief apart from its end, which is to act like God.

However little of this you are able to conceive, you may understand that to be like God is the way to be happy, and that if God has put it in your power to be like him, it is the utmost madness in the world to abuse your power by neglecting his treasures.[7]

In imitating God, we glorify God. In glorifying God, we glorify ourselves. What are those qualities of God that we imitate? “Knowledge, righteousness, and true holiness.”[8]

Our path to godlike virtue is not an easy or meditative one. In fact, it requires not just discipline and self-denial, but an almost violent warring against the flesh. Man must conquer every difficulty in order to receive the physical joy of virtue.[9] This earning of virtue increases our happiness, and without it, we could not receive the happiness that virtue affords after it has been won in the hard-fought fight of life.

There is in the late 17th-century author an undertow of humanistic vitalism which expresses itself repeatedly in hatred of inaction, contempt for inconsistency, and stoic resolve that all pain is for man soul-constructing.[10] He offers deep consolations for suffering: “we are to remember that our present condition is not that of reward, but labor.”[11] Those struggles on earth always serve a greater divine purpose, however, and no act of righteousness goes without purpose.[12] His encouragement to forgive our enemies because we were first forgiven is profound: “To be beloved in our guilt is exceedingly wonderful.”[13]

If Traherne’s Ethicks lean towards a Robinson Crusoe-esque ability for the individual man to straighten himself before God, it is because Traherne believes in an overabundance of God’s unmerited favor upon us. From time to time, the way Traherne will wax can almost leave the gentle soul crushed under his expectations of holiness and virtue, and then, at the last moment, the rays of God’s love for us while we were and are weak shine through.

One saint who felt those heavenly rays through the work of Traherne was a certain Clive Staples Lewis. It is Traherne who posits a version of the now immortal observation from Lewis that a longing that nothing on earth can satisfy must have a satisfaction beyond this world.[14] Traherne has a glowing account of how the little pleasures of this earth prepare our hearts for the greater pleasures of heaven.[15] His delight in creation, his joy, his belief in the purposefulness of all things, his cross-shaped rationality, his sense that all men could teem with God’s glory—the C.S. Lewis devoteé will find in Traherne’s Ethicks the missing prelude of a timeless symphony.

Notes

- Thomas Traherne, The Shining Human Creature: Christian Ethics, Vol. 1, modernized by Colin Chan Redemer (Landrum, SC: Davenant Press, 2023), ii. ↑

- Thomas Traherne, Made Like the Maker: Christian Ethics, Vol. 2, modernized by Colin Chan Redemer (Landrum, SC: Davenant Press, 2023), 53. See also The Shining Human Creature, 30. ↑

- Traherne, Made Like the Maker, 60. ↑

- Traherne, Made Like the Maker, 80-81. ↑

- Traherne, The Shining Human Creature, 11. ↑

- Traherne, The Shining Human Creature, 35. ↑

- Traherne, Made Like the Maker, 9. ↑

- Traherne, Made Like the Maker, 9. ↑

- Traherne, The Shining Human Creature, 33. ↑

- Traherne, The Shining Human Creature, 12. ↑

- Traherne, The Shining Human Creature, 21. He continues on: “Ours is an estate of trial, not of enjoyment. Our condition is that we are to toil, and sweat, and work hard for the promised wages; an appointed seed time for a future harvest; a real warfare to gain a glorious victory. Warriors in such a battle must expect some blows, and delight in the hazards and encounters we meet with because they will be crowned with a glorious and joyful triumph and be attended with ornaments and trophies far surpassing the bare tranquility of idle peace. When we can cheerfully look on an army of misfortunes without dismay, we may then freely and delightfully contemplate the nature of the highest happiness.” ↑

- Traherne, Made Like the Maker, 75. ↑

- Traherne, Made Like the Maker, 59. It’s places like this that Luther’s insights come to the fore and his moralism seems to recede to reveal a Gospel foundation, though it’s not on every page. ↑

- Traherne, Made Like the Maker, 14. ↑

- Traherne, The Shining Human Creature, 16-17. ↑