Reputation for Constitutional Cynicism

It may come as no surprise that many colonial Anglicans at the time of the Revolutionary War were Tories, who broadly opposed the Revolution. Gregg Frazer has provided the most recent history of this faction. The most famous example of the loyalist clergy is the first Bishop of the New World, Samuel Seabury, who was very active in writing tracts against Independence and the Revolution. When the war concluded many Anglicans were persecuted. Anglican churches were targeted under the suspicion that they were discontent with the new republic and fomenting Tory plots to undermine it.

Largely because of this and in light of the fact that Anglicans have historically been proponents of divine right monarchy, many Anglicans today are cynical about the American Constitution and the republican status quo which has dominated our republic for the last 250 years. Many will point to the deistic influence of some of the Founding Fathers, and the influence of the Enlightenment on the Revolution and rightly recognize that inclusion of such ideas was at least in part contradictory to many of the beliefs Anglicans hold about the trustworthiness of the Bible and Revelation, and salvation through Jesus Christ.

A Theory of Anglo-American Continuity

Here I will attempt to outline why I disagree with this cynicism from a principled Anglican perspective. I think that many Anglicans in the ACNA, like myself, have a great deal to learn from a summary of this issue. The Founding Fathers were attempting to forge a new system of government which in some ways represented the previous form of government they departed from, but also departed from its perceived flaws. Additionally, while there was a generation of groundbreakers who managed the split, it would actually be the next generation of young statesmen who would write the Constitution which would stand the test of time and define the American political framework.

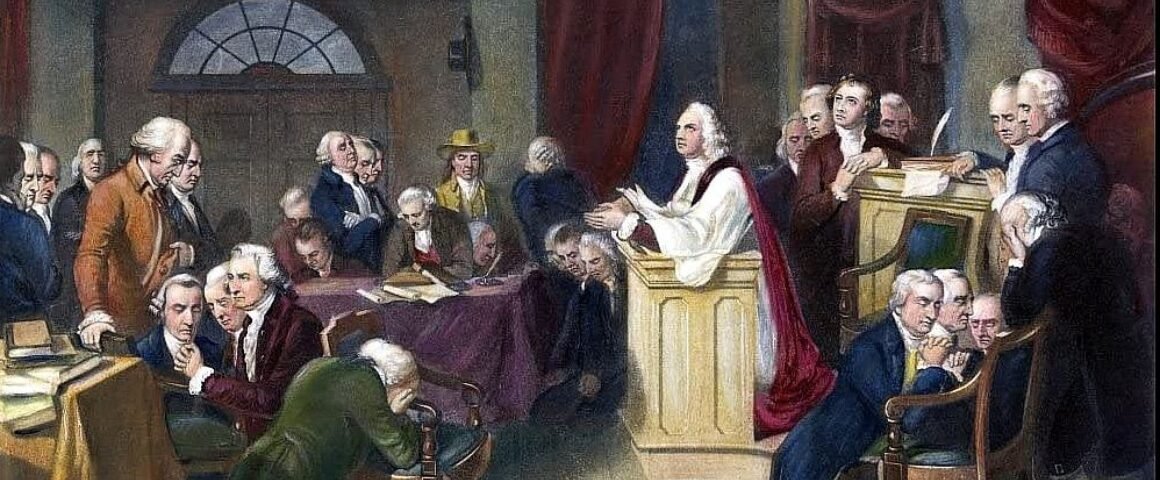

The principles which led most of the Anglican ministers (and indeed many loyalists) to oppose the Revolution were rooted in an opposition to the conflicting Enlightenment principles which the Revolution was ostensibly justified upon. Early radicals like Samuel Adams, believed strongly in the will of the people and democracy, and in the early stages of the conflict around taxation, many more conservative Americans thought of the Sons of Liberty as arrogant populist demagogues. Even still, while the Enlightenment had its influence on this faction, it was wrapped up in a traditional appeal to British liberties with their roots in medieval English Common Law. The early appeal was that the British Constitution, as it already existed, and was inherited in the colonies was being violated. John Adams, his cousin, who would eventually become a supporter of independence, represented a more conservative faction that believed in law and order and which would eventually be represented by the Federalists after the Revolution, and Sam Adams’ more populist faction would eventually be represented by the Democratic Republicans (which he would eventually join). This divide goes even further back into the colonial period with factions historians have retroactively referred to as the “proprietary” and “non-proprietary” factions, but the detail of this divide are beyond the scope of this paper. What convinced many conservatives, like Adams, to eventually support independence was largely the perceived violence of British soldiers and the desire of some British Tories to subdue the entire Continent by repression and force. Still, some American Tories like Samuel Seabury remained loyal and served as a chaplain to loyalist regiments. At the same time, other eventual bishops like William White, would eventually serve as the chaplain to the Continental Congress.

Still, the more conservative Americans who all opposed some of the underlying Enlightenment ideals were divided, (unlike the American Whigs who were all Patriots) and there were many conservative Patriots, who made up a formidable minority during the War.

The Limits of Enlightenment Ideals

And yet, when the war was won, it was these idealist Whiggish liberal populists who dominated the Continental Congress. But those idealists constructed, not the Constitution which would endure, but instead they wrote the Articles of Confederation which famously crashed and burned. The Articles of Confederation were built upon totally unrealistic ideals of totally voluntary association, localism, limited taxation, weak central government, and unrealistically broad civil rights. This meant that when even the smallest taxation or tariff was opposed, states (or even outraged individuals with some muskets) could not be compelled, and no serious projects could be achieved by the disunited and effectively independent states.

It became clear to a begrudgingly American populace that the Enlightenment ideals which looked so attractive on paper were much more difficult to actually put into practice. This is where Alexander Hamilton and James Madison’s more… pragmatic… idea began to gain popular appeal. Hamilton, who was fairly misrepresented as a liberal idealist in the recent popular musical, was actually a fairly Machiavellian cynic. He understood that any chance that the United States had of being a real power which would not just be reconquered by her former imperial overlord (which almost occurred in 1812) would require some concessions to the fundamental laws of power and reality. Put simply; it meant getting our hands dirty.

Recognized at an early age for his intellectual ability, he was sent to King’s College (now Columbia) in New York City, from his remote island home in the Caribbean, by supportive community members. As a teenager he argued in the press in favor of the Revolution against Rev. Samuel Seabury’s loyalist tracts, despite the fact that Seabury was more than 25 years his senior. As a 20 year old (or possibly actually an 18 year old) he had enlisted in a Patriot Militia, made a number of important connections, raised his own artillery battalion, and became General Washington’s aide-de-camp. He married above his pay grade into one of the oldest American landed gentry families, the Dutch Schuyler family (further connecting him to this pre-Revolutionary “proprietary” faction). Even as a young man he was thinking very ambitiously and very practically.

After the war was won he became a lawyer and a politician, heavily criticizing the new Congress and the Articles as being unfit for both “war and peace” on account of the fact that it gave the Congress no real power. This was fairly unpopular at the time but he had no qualms with saying unpopular, yet true things. He was not opposed to the idea of making George Washington king (although Washington himself vehemently opposed the idea), and was much more similar in his conception of politics to classical figures like Aristotle who thought good government had three core elements: monarchical, aristocratic, and democratic. In his time, the only popular talking point was more more more democracy, but he was unafraid of arguing for less democracy. He enlisted the more careful Madison to support his bold rewrite of the Articles of Confederation. Rather than amending the Articles, he proposed an entirely new Constitution. Perhaps as a tactic to make his ally Madison appear more moderate, Hamilton then argued in front of the Constitutional Convention in favor of an almost comically authoritarian new system of government with a king, and a whole swathe of unelected bureaucrats, appointed from the top down to ensure unity in this new and muscular federal government. What resulted from the tumult of this period was Hamilton and Madison’s success in proposing an entirely new constitution which learned, not mostly from the contrivances of Enlightenment philosophy, but from history and the British system. James Madison famously carried books around with him in his pockets all day during this period reading about the rise and fall of the world’s historic republics like Rome, Athens, and Venice in an attempt to learn from their mistakes and to craft a more enduring system. In a rapid pamphlet war, Hamilton and Madison’s Federalist Papers turned public opinion in favor of the new Constitution which was ultimately ratified.

A Failure in Total Revolution

In many ways, just like every other revolution in human history, the American Revolution was a failure. It was forced to largely concede many of its ideals of limited government in favor of a much more pragmatic and conservative Constitution. Thomas Jefferson, who was entirely taken by Enlightenment fervor and was much more of an idealist hated the Constitution. However, despite Jefferson’s eventual Presidency and the near absolute victory of his party for decades, he could not undo Hamilton’s Constitution or many of Hamilton’s other political constructions like the Bank of the United States.

The fundamental genius of the British system (which has since been abolished in recent years) was the combination of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. The hope of the American Whig populists was to abolish that system and replace it with thirteen state democracies loosely connected only by voluntary association that could be revoked or contradicted at any time. Instead, the Constitution which prevailed preserved much of the genius of the British system, perhaps with a modified version of the jewel in the monarchy. Yet, Hamilton was able to create a Presidency which passed muster and performed much the same function as the British monarch. The state governments, in the original design, produced an aristocratic class that could still be held responsible to both the electorate and state governments, represented by the Senate.

The idealism of a movement’s first generation often makes Revolutions unstable, and creates a power vacuum for energetic pragmatists. The same trend has been noticed in nearly every other Revolution.

The Case of the Anglican Church in North America

Now, the Anglican Church in North America is far from a revolutionary state. In fact, much of our goal is reactionary and attempts to recover the historic Anglican tradition here in America. But like any young institution we also live with many of the contradictions presented by our unnatural birth. The first generation can easily be so swept up in the vision, high in the sky, which brought their idea into being, that they don’t realize they are standing on train tracks. The task of the 20-year-old militiamen on the battlefield is to get real.

Christianity is a realist religion. Contrary to the popular idea of a noble fiction, and leap of faith towards a possible ideal, Christianity is fundamentally rooted in the facts of the situation. As St. Paul put it so succinctly: “and if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain.” (1. Cor. 15:14). Our faith is rooted in fundamental immutable facts. So there is nothing to be ashamed of in considering yourself a realist.

I am often surprised to find that some conservatives, especially on issues like the ordination of women, are afraid of loudly, vocally, advocating for the eradication of the errors permission in our Province, out of a desire to play well. But we have reality on our side. We ought to believe we are objectively correct or else there is no point in believing what we believe. If we are correct, and our advocacy for the truth protects both sheep and prospective “shepherds” from being misled into error and unorthodox ministry, the noble, loving thing to do would be to push for our view. It might not be popular, but we are obliged by duty to think, much like Alexander Hamilton, about how we can best situate ourselves for victory. The difference between ourselves and Alexander Hamilton is that we are on the side of the divinely instituted and protected Apostolic Deposit of faith. We quite literally have God and C.S. Lewis on our side.

“Wise As Serpents and Innocent as Doves”

So what can we learn from Hamilton? Well, I would say that Our Lord put it more succinctly than Alex ever could: “Be wise as serpents and innocent as doves.” (Matt. 10:16). Notice here, Jesus does not say “but”, as if the two traits were contradictory, but instead he says “and.” There is no contradiction in being wise and being innocent. Innocence pertains to goals and intentions, while wisdom pertains to the means we use to achieve those goals.

It is for this reason that I believe we should consider the plain evidence of history and logic in raising a generation of Anglican statesmen. If the ACNA is going to be a serious institution in America we have to learn from the mistakes of previous comparable institutions. Much like Madison, we ought to hold these lessons of history close to our hearts, in order to learn what can be learned. Our advantage is that much of the structure of the ACNA has corrected some of the errors already, and all we need to do is to preserve and police those gains.

One of the lessons which I believe has already been learned by the framers of the ACNA’s Constitution and Canons was actually fixing the mistake of sainted Bishop William White in imbibing some of the errors of his own time and incorporating lay representation in doctrinal decision-making for the Episcopal Church. For one, we actually have a “metropolitan” Archbishop who the bishops owe canonical obedience to, rather than a figurehead presiding bishop. But more importantly, the issues of doctrine are reserved for the College of Bishops, rather than being voted on by the General Convention (as if the truth was determined by a consensus of the uneducated). For more on the differences, there is a wonderful substack called Detestable Enormities which breaks down the canonical differences in the structure of the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Church.

On Anglican “Fundamentalism”

Another lesson I think can be learned from the “Anglican Fundamentalists” (a better term for this group might exist but I think it accurately summarizes a tendency in the Anglican and indeed Christian world). The Continuum and the UECNA represent purists from their respective persuasions, be they Anglo-Catholic or Reformed which were incapable of creating a broad enough consensus to remain united. Even the Continuum is further divided into even smaller denominations. The G3 works towards organizational unity now, which is certainly good, but altogether they only make up some 179 active congregations which are often very small. There is nothing inherently evil about this, but it is certainly undesirable. I think we can all agree that a larger traditional Anglican province would be the most desirable. So let us labor for just that. What this will mean though is putting aside particular persuasions within the orthodox movement. I see the divide between Anglo-Catholics and Anglo-Reformed as being largely bad for the Church.

Unity on essentials is vital. The opposite is equally true. Disunity on non-essentials is deadly.

The ACNA has attempted to correct for this error with the much-maligned “Three Streams” idea. This idea has its underlying merits, obvious problems and anachronisms notwithstanding. The spectrum of high to low church Anglicans has been with us since time immemorial, and it will not be resolved by our personal pet projects or internet blogs.

What can be accomplished by two men alone, exponentially grows when they combine their energies, and the effects multiply as the numbers increase. Creating cradle-to-grave cultural institutions for Anglicans across the jurisdictional divides, like schools, magazines, hospitals, charities, missionary organizations, and others is a serious project that ought to be accomplished with full vigor. I am pleased to see a growing network of Anglican Christian schools in the ACNA, as well as projects like St. Dunstan’s Academy affiliated with the APA. Where small, scattered, similar institutions exist, let us labor to unite them and consolidate their efforts.

The Threat of Mission Drift

The obvious threat, that goes almost unspoken of, is warding against mission drift. This is fundamentally the practical cause of so many theological novelties. The simple Gospel and the old Apostolic Faith becomes boring, and other projects become more attractive, and so the Church is roped up into those other projects and the faith is twisted and squeezed to conform to those project goals. Theological liberalism is applied in these cases to resolve the clear tensions between these distractions and the Biblical faith. This is why theological liberalism in Nazi Germany bent in a very opposite direction to theological liberalism in the modern United States, but both were theologically “liberal” in that they treated the Apostolic faith “liberally” or loosely. The obvious reaction to this is to instead hold the Apostolic faith tightly. This will mean excommunication of heretics and propaganda. Both of which have a bitter association in the mouth of moderns, but are utterly defensible when carefully considered.

Excommunication is the separation of the wheat and the tears, and the protection of the sheep from the wolves in sheep’s clothing, on top of being an exhortation to repentance on the part of the excommunicated. The shepherd’s staff, or crosier is a fundamentally offensive tool which pokes and prods the sheep in the right direction, but also is used as a weapon to ward off predators.

Propaganda as a term originates with the medieval catholic church, and pertains to the propagation of the truth. Modern methods ought to be employed to propagate the truth. This was the genius of the Protestant Reformation’s embrace of the Printing Press, when so many rejected it as destabilizing. As a YouTuber and general social media guy, I believe that it is a comparable platform that has to be embraced. If it is ignored it will become a propagation platform for our enemies. This means making propaganda of all kinds. Simple propaganda meant to excite the viewer, should accompany more long-form propaganda in the form of formal apologetics work. Goodness, truth, and beauty speak of God and are tools of the evangelist in order to relate Him to others.

This also means a robust defense, not just of “Mere Christianity” but of Anglicanism as such. If we are Anglican and convey to others that they would be “just as well off” in any other denomination, not only are we basically telling them that we don’t believe what we are often saying, but we ourselves make Anglicanism into an affinity-based club, rather than what it ought to be which is the Catholic Faith truly exposited and protected. So no “simping” for other denominations. Anglicans who think Anglicanism is just English Roman Catholicism will be flogged (just kidding) and Anglicans who think Anglicanism is just Presbyterianism (or God forbid non-denominationalism) with funny hats will also be flogged (just kidding).

Defending Essential Commitments

The Lambeth Quadrilateral must be defended. It is received, not as a full exposition of any particular intra-ecclesial faction, but as the very essentials which would have to be agreed upon before further conversation could even be had. Much can be entailed from the Quadrilateral, and the Thirty-Nine Articles require more than they do, but the Thirty-Nine Articles have not been “catholicly” binding. They are binding on Anglicans, but not until they were constructed and not in other provinces with which we would have recognized as catholic Churches during the Reformation and since. In my estimate, the Thirty-Nine Articles represent the fullness of the faith, but the Lambeth Quadrilateral represents the boundaries. They are:

1. The Holy Scriptures, as containing all things necessary to salvation;

2. The creeds (specifically, the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds), as the sufficient statement of Christian faith;

3. The dominical sacraments of baptism and Holy Communion;

4. The historic episcopate, locally adapted.

We disagree with (nearly) every protestant sect on the last count, but we disagree with the Romanists and the Easterners on the first and second count (in that they require doctrines outside of the creeds and the Holy Scriptures as necessary to salvation). Where then, but to the Anglican Church, could we safely send anyone?

It is for this reason we must zealously defend her, proclaim her, and advance her interests. It is for this reason that for hundreds of years loyal Anglicans and Episcopalians have called themselves “Churchmen”, and dedicated their lives to the Church.

Therefore take up your pens, and lift up your hearts to the Lord, as a generation of statesmen—nay, Churchmen—with a great deal of work ahead of us.

'Young Anglicans for the Constitution' have 2 comments

December 14, 2024 @ 9:14 am Andrew

\”I think we can all agree that a larger traditional Anglican province would be the most desirable.\” I don\’t see why all must agree with this, I certainly don\’t. Is holiness, catholicity, and orthodoxy a function of the size of the church? The size of the G3 churches seems just fine to me. We live in a time of increasing fragmentation, our duty now is to remain faithful as best we can under the circumstances. It seems unlikely to me, in any case, that the ACNA will survive its internal contradictions for much longer.

\”The spectrum of high to low church Anglicans has been with us since time immemorial\”. This is true only if you think our tradition started in the 16th century and completely ignore 1500 years of previous history. The Ecclesia Anglicana is not synonymous with the Church of England. It existed before the Church of England and still exists after the Church of England has fallen.

As for the Thirty-Nine Article, they are 16th century–i.e. recent–novelties. We have a rich and ancient tradition: Bede, Aelfric, St. Anselm, Julian of Norwich, Walter Hilton, Richard Rolle, and many others. There is much worthwhile in Cranmer, the Caroline Divines, and the Tractarians when read in the context of our entire tradition. In this tradition, not in the 39 Articles, will you find the fullness of the faith.

December 18, 2024 @ 1:44 pm Greg

“Where then, but to the Anglican Church, could we safely send anyone?” So true, so very, very, very true.