Anglicanism After England and Hooker’s Two-Legged Stool

~

There was once a time in England (and, therefore, in these United States also, still being in the loins of her ancestor) when the execution of a careful argument was valued as a demonstration of the soundness of the premises being proposed. We used to believe that “Truth cannot belong both to the Affirmative and Negative Side of the same Proposition,”[1] and faith in the Truth (Who is, of course, Christ) drove us into the fray of honest scraps with our interlocutors, a Christian tradition as old as the apologetics of Origen, Justin Martyr, and Tertullian.

One of the perennial subjects of such debates for the Ecclesiae Anglicanae against her Puritan detractors was (and remains) the role of Holy Scripture in the life of the Church. Richard Hooker “the Judicious” famously challenged the regulative principle of the burgeoning Genevan tradition, arguing in 1593 what had already essentially been enshrined in 1571 with Article 34, “Whosoever through his private judgement, willingly and purposely doth openly break the traditions and ceremonies of the Church, which be not repugnant to the Word God, and be ordained and approved by common authority, ought to be rebuked openly.” In his magnum opus, Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, Hooker constructs a defense against what could be called a “totalitarian” hermeneutic of Scripture, a myopic fixation on the only feasible institution of authority remaining after the various European reformations. Some have described Hooker’s defense as a “three-legged stool,” consisting of Scripture, Tradition, and Reason. I would like to humbly suggest here that it might be more accurate to speak of a “two-legged stool,” those legs being Scripture and Reason alone. This interpretation of Hooker seems warranted, given what he writes in chapter XIV of Book I (section 5):

It sufficeth therefore that Nature and Scripture do serve in such full sort, that they both jointly and not severally either of them be so complete, that unto everlasting felicity we need not the knowledge of any thing more than these two may easily furnish our minds with on all sides; and therefore they which add traditions, as part of supernatural necessary truth, have not the truth, but are in error…For we do not reject [traditions] only because they are not in the Scripture, but because they are neither in Scripture, nor can otherwise sufficiently by any reason be proved to be of God.[2]

Curiously, Hooker later concedes:

That which is of God, and may be evidently proved to be so, we deny not but it hath in his kind, although unwritten, yet the selfsame force and authority with the written laws of God. It is by ours acknowledged, ‘that the Apostles did in every church institute and ordain some rites and customs serving for the seemliness of church-regiment, which rites and customs they have not committed unto writing.’ Those rites and customs being known to be apostolical, and having the nature of things changeable, were no less to be accounted of in the Church than other things of the like degree; that is to say, capable in like sort of alteration, although set down in the Apostles’ writings. For both [unwritten and written rites/customs] being known to be apostolical, it is not the manner of delivering them unto the Church, but the author from whom they proceed, which doth give them their force and credit.[3]

Dear reader, if you are having difficulty understanding this passage that comes to us from 430 years in the past, you are not alone. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve read and re-read this section. However, the modernization published by the Davenant Trust is quite helpful, rendering some of the more difficult bits as follows:

We do not deny that even unwritten traditions, if they could be proved to be from God, would have the same force and authority as the written laws of God. We acknowledge that the Apostles instituted and ordained certain rites and customs for the sake of orderliness in the church, which rites and customs were not committed to writing. However, these Apostolic rites and customs are changeable. We grant them no less weight than any other such changeable rites in the church, even those that are set down in the writings of the Apostles. For although both are Apostolic, it is not the way they are delivered to the church, but God from whom they spring that gives them force and credibility.[4]

Aided by this rephrasing, we might begin to see that Hooker does not appear to have a problem countenancing the possibility of an authoritative unwritten command per se. He would not dismiss such a hypothetical command out of hand simply because ink and paper were never employed in its transmission. Rather, the Good Doctor simply does not believe that the unwritten instructions in question ought to be considered “divine and holy.” Why? Here’s the rub: because they aren’t found in Scripture and there does not appear to be sufficient Reason to receive them as anything other than changeable and capable of alteration.

For any of you who have ever tried to get comfortable on a two-legged stool, you might sympathize with my wariness at this point. To be clear, Hooker’s system is genius. Consider his predicament. On the one hand, he can’t concede to Scripture alone the kind of authority maintained by the Genevans. Otherwise, they would be right in dismantling the Established Church. But he also cannot concede to Tradition the kind of authority maintained by the Romans. Otherwise, they would be right in excommunicating the Established Church. Ah, another via media (they spring up everywhere once you begin looking for them)! Hooker is therefore left making uneasy bedfellows of Scripture and Reason (“jointly and not separately,” mind you).

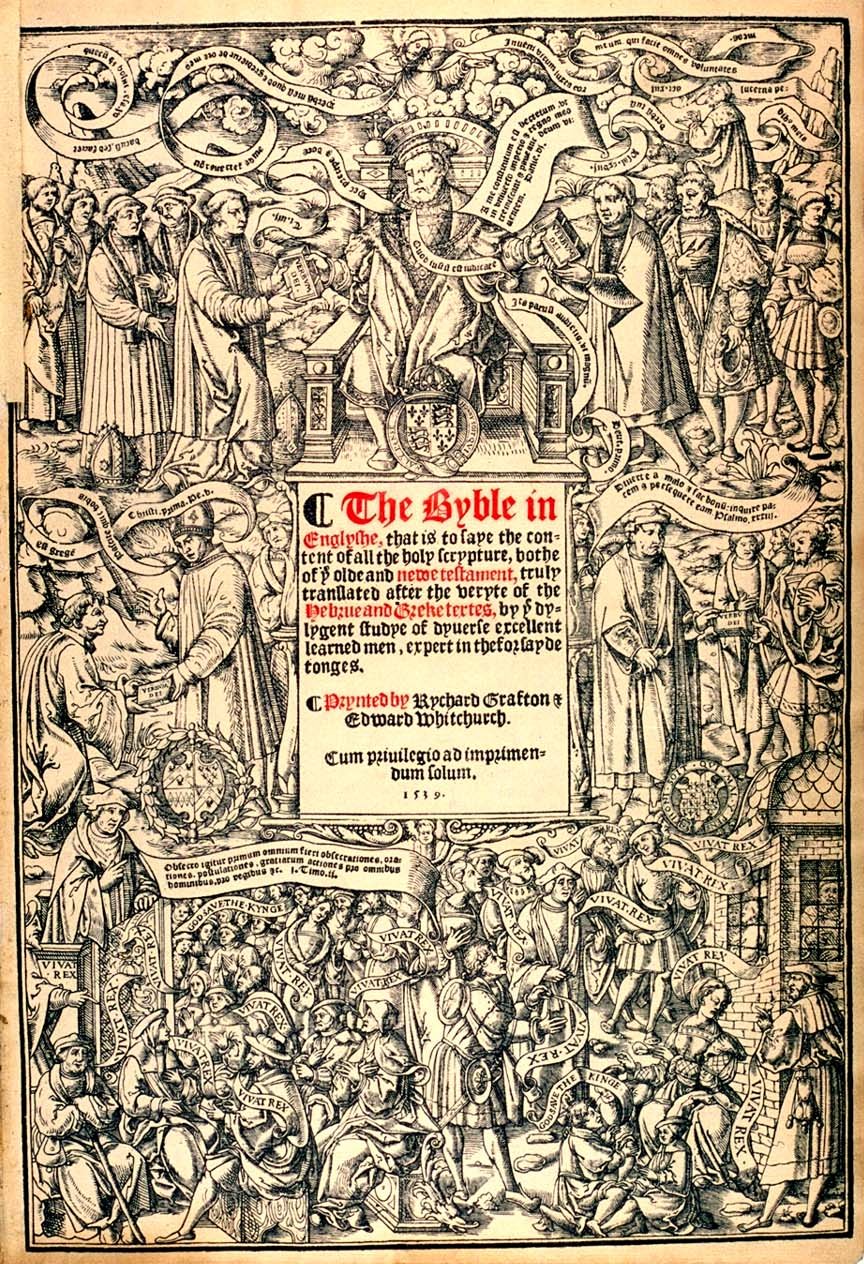

However, propped up on his two-legged stool, Hooker himself seems to recognize the precariousness of the arrangement. The balancing act requires another stabilizing force. So he understandably juts another pillar under the argument: the State. His elegant system deftly unfolds earthly law out of the heavenly law, “…there can be no doubt but that laws apparently good are…things copied out of the very tables of that high everlasting law; even as the book of that law hath said concerning itself, ‘By me kings reign, and’ by me ‘princes decree justice.’”[5] This Platonic descent (incarnation?) of truth is also expressed in the title page of Henry VIII’s “Great Bible.” I first discovered this “spectacular piece of reformist iconography”[6] while reading Diarmaid MacCulloch’s biography of Thomas Cranmer.

This piece of propaganda presents the King as a fairly seamless replacement for the Pope. Representatives for both the Church and State line up at either side of the king’s throne, from which he graciously dispenses the Word of God[7], which then trickles down to the common folk in their respective spheres. Paul III may have been the head of the Roman Church, but Henry VIII absolutely understood himself as the head of the English Church. The weight of Tudor majesty worked well to prop up Hooker’s stool for the moment.

The title page also perfectly embodies what I discovered, while digging into the Nonjurors, to be a deeply entrenched tenet of the established Church of England in the 16th and 17th centuries: what the Rt Rev’d John Lake, Lord Bishop of Chichester (and one of the Immortal Seven that delivered the famous Petition to James II), called what he “took to be the distinguishing character of the Church of England,” namely, “the doctrine of non-resistance and passive obedience [to the sovereign].”[8] Of course, the Nonjurors famously demonstrated how to faithfully apply such a doctrine, acquiring firsthand knowledge along the way of what happens when Hooker’s third, improvised leg of the State/Sovereign can no longer be relied upon. Nevertheless, they were the children of an Establishment that prized and preserved what Peter Nockles called “an almost mystical, sacral theory of monarchy,” such that a “conviction of the inseparable connection between political insubordination or disloyalty and theological heterodoxy was commonplace among” the Establishment Party.[9] This understanding of the monarch is literally enshrined in the cult of the “Royal Martyr,” Charles I.

Time and space would fail for me to rehearse the history of the Nonjurors here. Let it suffice to say: their loyalty to their papist king (James II) made them exiles in their own home. This did, however, yield the intriguing phenomenon of a Church of England communion cut off from England, a state of affairs that should be of particular interest to those in the Anglican tradition currently coalescing around GAFCON and the GSFA. With their sworn king, like them, exiled and cut off from the kingdom, the nonjuring communion had the privilege of (all too briefly) representing an Anglican fellowship without an earthly king. And slowly, no longer having the advantage of the third leg of the monarch as a source of authority, some of their number reached for the other, older pillar Hooker had discarded: the Tradition.

Jeremy Collier, Thomas Brett, Thomas Deacon, Archibald Campbell, and others came to represent a party within the later Nonjurors seeking ancient foundations. This would even go so far as to eventually result in overtures from the Nonjurors to the Patriarchs of the Eastern Church in talks of possible intercommunion (which, of course, came to nothing). Even before this, however, they proposed the “Usages.” The Usages consisted of four items:

(1) that Water is an Essential Part of the Eucharistic Cup.

(2) that the Oblation of the Elements to God the Father; and,

(3) the Invocation of the Holy Spirit upon them, are Essential Parts of Consecration. And,

(4) that the Faithful departed ought to be recommended in the Eucharistic Commemoration.[10]

These usages all remained (mostly) intact in Edward VI’s first prayer book, and the majority of the nonjuring community would eventually accept a version of the 1549 rite, although there was an initial division between those who did not want to introduce additional obstacles to reunion with the Established Church and those with no qualms plowing ahead on their own. As with most things at the time, the battle was waged with volleys of missives, protracted arguments back and forth with pen and paper. One such interchange pertinent to our topic can be found in the preface to Thomas Brett’s Collection of the Principal Liturgies.

I am not actually certain who wrote this preface, as there is no name affixed and Brett himself is referred to in the third person. One wonders if it might have been Jeremy Collier himself, who regularly engaged in the debate. Regardless, the author defends the usages with a forceful appeal for the place of Tradition in the life of the Church, and I hope the reader will indulge me in quoting segments of his writing at length.

He begins by summarizing the argument of his opponent (almost certainly Nathanael Spinckes)[11] as consisting of two propositions:

(1) “Scripture is prescribed by our Lord to his Disciples as the only Rule they are to walk by.”

(2) “Tradition is not prescribed by our Lord to his Disciples, as the Rule they are to walk by.”

Before continuing further, the author makes it clear, “I hold the Holy Scriptures in as high Esteem and Value, as this Gentleman, or any other Person living. I believe them to be the Word of GOD, and consequently true, and that if Controversies do arise concerning Religion, there is no Appeal from their Determination.”

Interestingly, the author of the Preface is in a position not entirely dissimilar from the one Hooker was in: one party is wielding the authority of Scripture against the Tradition of the Church. But where Hooker, assuming the best of man’s use of Reason, appealed to the State to fill the void left by Tradition, the author of this preface appeals to the Lord Jesus Christ and His Apostles:

If this be true [that Scripture was prescribed by the Lord as the only Rule to walk by], I am afraid it will very much sink the Credit of the New Testament. For if Scripture is prescribed by our Lord to his Disciples as the only Rule they are to walk by, it must be such Scripture as was in Being at the Time when he gave that Direction; consequently the Scripture of the Old Testament, for the New could be no part of that Rule, because not any one Book of it was wrote till several Years after our Lord was ascended to the Right Hand of his Father, and had ended his Conversation with his Disciples upon Earth.

Accordingly:

[Spincke’s] Arguments, which if they prove anything to his Purpose, must conclude against the Authority of the New Testament; we firmly believe it to be the Word of God, and written by the Assistance of his Holy Spirit…this Gentleman’s Doctrine having no ‘Foundation in the Scriptures,’ cannot be confirmed by them. And therefore he must either give it up, or acknowledge that he does receive it ‘barely upon Tradition.’

We find in this preface an argument that is almost startling in its simplicity. The author advocates for an understanding of Scripture as being seated within and growing out of its natural habitat, the bosom of the Church, rather than being a kind of Quranic, self-contained, self-sustained divine reality (or as some have lately put it, being “its own interpreter”). The author lays out a straightforward sequence: “For our Lord was not the Messiah and Saviour of the World, because his Disciples taught that he was; but because he really was so, they taught it; and after the Authority of the Law-giver was owned, they proceeded to teach his Law.” The author shifts the focus back onto Christ as the Supreme Authority and the Church He established, rather than the state-sanctioned appropriations of Scripture and Reason that Hooker and other advocates of the Establishment were forced to content themselves with.

The author of the preface later reflects on Spinckes’ treatment of the word paradoseis in 1 Corinthians 11:2 (“Now I commend you because you…maintain the traditions even as I delivered them to you.”). Spinckes writes:

“…nothing more can be meant by Traditions in these Places but the Doctrines the Apostles had taught the Christians, whether by Writing or Word of Mouth. And if no more be intended by the Ordinances here referred to, I know no Occasion there is for any Dispute about them,”

to which the author of the preface responds:

“Nor do I know any Occasion for Dispute, if so much be intended by them. For if the Apostles taught some Doctrines by Word of Mouth, that is by Tradition, which they did not commit to Writing, as this Gentleman owns; I shall conclude, that our Lord did not exclude Tradition from being a Part of the Rule which Christians were to walk by.”

The author ends the preface by, after reminding his readers that St. Luke’s gospel essentially represents a compilation of oral testimony, asking if they “will take Part with this Gentleman in the Support of his Assertion, or with St. Luke for the Authority of his Gospel.” It’s a fair question.

Hooker openly acknowledged that the Apostles “did in every church institute and ordain some rites and customs…not committed unto writing,” but he dismisses their authority since he can’t find them in Scripture “nor can otherwise sufficiently by any reason be proved to be of God.” Yet here, in Brett’s preface, someone else considers these unwritten teachings and concludes they are part of our Rule. Both Hooker and Brett’s preface use Scripture and Reason. To ensure the equilibrium of his system, Hooker naturally appealed to the rule of the godly prince. But what if the Sovereign defects?

By the time this is published, Charles III will be crowned King. With that old, time-tested English subtlety, His Majesty once suggested he would serve not only as “Defender of the Faith,” but also “Defender of Faith.”[12] Accordingly, the new monarch is politely allowing representation across the spectrum of spiritual expression within his coronation rite, including “representatives from the Jewish, Sunni and Shiite Muslim, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, Bahai and Zoroastrian communities.”[13] As a 21st-century American, I can certainly understand the logic of such an approach. It seems obvious that the sovereign of a multireligious state has an obligation to signal the inclusion of all his subjects. But it is also just as obvious that a system of hermeneutics built around such an institution can no longer be relied upon to defend and proclaim “the faith that was once for all delivered.” The Kigali Commitment acknowledges this reality with a unanimous vote of no confidence in the see of Canterbury. Anglicanism has outlived England, and she must once again decide how to keep the stool stable. Perhaps, like the Nonjurors, she will remember that “wonderful and sacred mystery,” the Church, and allow Tradition to resume its place of authority. Or perhaps she will learn to get comfortable on a two-legged stool.

Notes:

- Brett, Thomas. A Collection of the Principal Liturgies, Used by the Christian Church in the Celebration of the Holy Eucharist, &c. Richard King: 1720, p. vi. ↑

- Hooker, Richard. Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity. vol. 1. J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd: 1958, pp. 218-219. ↑

- Ibid., p. 219. ↑

- Hooker, Richard. Divine Law and Human Nature: Or, the first book of Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, Concerning Laws and their Several Kinds in General. ed. W. Bradford Littlejohn, Brian Marr, and Bradley Belschner. The Davenant Trust: 2017, p. 85. ↑

- Hooker, Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, p. 225. ↑

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. Thomas Cranmer: A Life. Yale University Press: 1996, p. 238. ↑

- Though Henry shamelessly often sought the execution or imprisonment of those that made the English translation possible. ↑

- Overton, J.H. The Nonjurors: Their Lives, Principles, and Writings. Smith, Elder, & Co.: 1902, 81. ↑

- Nockles, Peter Benedict. The Oxford Movement in Context: Anglican High Churchmanship, 1760-1857. Cambridge University Press: 1994, p. 48-50. ↑

- Brett, Collection of the Principal Liturgies, p. iii. ↑

- Nathanael Spinckes (1653-1727) was another nonjuring bishop who came to be aligned with the more moderate wing of the party (more in the vein of Thomas Ken, Henry Dodwell, and Robert Nelson) ↑

- Sherwood, Harriet. “King Charles to be Defender of the Faith but also a defender of faiths.” The Guardian, September 9, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/sep/09/king-charles-to-be-defender-of-the-faith-but-also-a-defender-of-faiths ↑

- Booth, William. “In coronation twist, King Charles to pledge to protect ‘all faiths.’” The Washington Post, April 29, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/04/29/king-charles-iii-coronation-will-recognize-people-all-faiths-including-jews-muslims-hindus/ ↑

'To Whom Shall We Go?' have 2 comments

May 25, 2023 @ 7:20 am John

Fr. Logan,

Thank you for this article. The history of the Non-jurors is interesting, and I am intrigued to learn more. If I am reading you correctly, you are claiming that Hooker, in constructing a defense of the English Church’s Reformed Catholicity against her Puritan and Roman detractors, rejects Tradition as an establishing factor of her teaching, and replaces it with the laws of the Magistrate. If this is your argument, then based on the three passages of the “Laws” which you quote it seems rather spurious. Particularly, it appears to be based on an equivocation of what Tradition means. The Roman Catholics mean by Tradition authoritative commands of God, coequal with Scripture, which are nevertheless not written down in Scripture, but supposed to be passed down through generations of Fathers, Doctors, and Bishops. This is the Tradition Hooker rejects in the first passage you quote, when he says “therefore they which add traditions, *as part of supernatural necessary truth*, have not the truth, but are in error.” The specification that these Traditions are “part of supernatural necessary truth” identifies them with the Roman conception. This, however, does not require a rejection of Tradition as the hermeneutic of interpretation of the Holy Scriptures, maintained by the Fathers and subordinate to the Word Written, which Hooker maintained against the Puritan errors.

Secondly, I struggle to see how your second quotation of Hooker, in which he discusses the relationship between temporal human and Divine eternal laws, bears the weight of your assertion that he is making the Crown/State a necessary bulwark of the English settlement. While certainly he and the other Anglican divines held Christian princes to have a vital role in preserving, protecting, and governing the Church, in that book of the “Laws” (if my recollection is correct; I do not have the book in front of me) he is discussing how human laws and the Law of God are related generally, and not affirming a kind of caesaropapist view of the King as constitutive of the Church.

I am also not sure how the situation of the Non-jurors applies to the current moment in the Communion. While the Kigali Commitment is certainly a momentous and historical statement in this history of Anglicanism, in many ways divesting from Canterbury does not pose a significant change in the lives of individual provinces – particularly when it comes to doctrine. In the United States, Anglicanism has been entirely independent from England for nearly 250 years. Official bodies of inter-Anglican conciliarity have been voluntary associations, and have existed for 150 years; namely, the Lambeth conference. Even within the Church of England, the King and Parliament do not and never have been able to decide the doctrine of the Church; the civil Magistrate has only ever had authority over her temporal governance. Therefore I am genuinely unsure what you can be referring to by “a system of hermeneutics built around such an institution.” As far as I am aware, no such hermeneutical system built around the current English Monarchy and practiced by global Anglicanism exists.

Forgive me if I have misunderstood your meaning. Thank you again for your piece.

John

May 26, 2023 @ 12:58 pm Daniel Logan

Thanks, John, you’re being quite gracious, I appreciate that.

Those particular prooftexts of Hooker may very well not be capable of carrying the weight of my argument, I’ll admit. Even after spending a fair amount of time reading the Doctor of blessed memory, I’m still not sure if I actually know what he was saying. I gladly defer to my betters on that score.

What I (perhaps unsuccessfully) was trying to articulate was a sense I took away from reading the Laws which I suspect has been a temptation in every age (at least since the Church made her peculiar partnership with Empire), that the honor of the throne may have swayed affections and ever so slightly tipped a scale that must be attended with absolute, exacting caution. Perhaps not in so many words (hence the weakness of my citations), Hooker (and others before him; we must remember Cranmer’s legal/diplomatic favors to Henry) may have made a strategic error in their selection of weapons while defending England’s dynamic ressourcement of the Faith. I suspect they reached for the authority of the sovereign (a natural, self-evident choice at the time) when they should have reached for the authority of the Church (though interestingly Hooker preferred to speak of the Commonwealth, planting a seed that may have birthed the nation of my earthly birth – he beat Hobbes to the punch).

But how could they have? We must be sympathetic. I am confident it would have been well-nigh impossible given the (far too literal) Damoclean (Diocletian?) sword of the sovereign on one end and Rome’s poisoning of the well on the other.

And Hooker, irenic and kind man that he was, clearly wanted to build a bridge to his countrymen who had become so inflamed with the Genevan vision. Certainly we can admire such a passion for peace.

However, in my own humble delving into the (comically unpopular; cf. Colley Cibber’s play, The Non-Juror) nonjurors, I’ve come to believe they show us a better way. Anyone anxious to understand relations between Church and State, regardless of any particular tradition, should endeavor to drink deeply from their well. The Church is free. Following Chrysostom, Basil, Athanasius, we must be prepared to give the Emperor honor and truth. The nonjurors’ insistence on the independence of the Church paved the way for Keble’s Assize Sermon (though the Newmanites often treated their forebears unfairly).

Protestants cry “Semper reformanda!” (though I wonder if such a theological instinct ultimately has more in common with Newman’s Development of Doctrine than they would ever care to admit). The point of my little essay is to suggest that the terms of perpetual reformation might allow for a revisiting of our ancestor’s doctrinal settlement. Might it be time to give Tradition something closer to her former due?

And yes, I make an egregious leap over developments in the interim (e.g. America), though this is not because I am not aware of them. Yes, we edited the Articles. Yes, we briefly excised a creed. We did just fine without bishops for quite sometime. I’m just not sure if those developments were faithful to our patrimony or even advisable. (Calm down everyone, I’m still a patriot) My heart (as is the case with many of us younger priests) has always been with classical “Anglicanism,” an ad fontes instinct that the ACNA clearly shared in its (unfortunately nominal) resumption of the classical Formularies in all their pre-American glory.

I’m not sure I’m making sense. Sorry if I’ve caused any confusion. A dear Friend and Father in the Faith recently shared with me the closing lines of a sermon Hooker once delivered on pride, which seem to follow the example (in tone of not in fact) of St Augustine with his retractions or St Thomas Aquinas with his famous “straw” comment, and I’ll end with them:

“My eager protestations, made in the glory of my ghostly strength, I am ashamed of; but those crystal tears, wherewith my sin and weakness was bewailed, have procured my endless joy; my strength hath been my ruin, and my fall my stay.”

With deep love and respect for our Angelic Doctor (ora pro nobis) and affection for all,

Daniel