Introduction

On March 11, 1997, Neil Postman delivered a lecture to an Illinois community college entitled “The Surrender of Culture to Technology,” in which he presented seven questions that should be asked when confronted with new technologies. Public debate at the time centered around the installation of public-school computers with access to the emerging “world wide web.” Postman applied these questions to this debate and encouraged the audience to do the same, as “only a fool would blithely welcome any technology without having given serious thought not only to what the technology will do, but also to what it will undo.”

Recently, TNAA published an essay hailing the arrival of the Anglican Church in North America’s To Be a Chistian catechetical app, now available on the Apple or Google app store. In this essay I aim to briefly analyze this newly released app through Neil Postman’s seven questions.

Question #1: What problem is the technology claiming to solve?

The ACNA publicized the release of the app, announcing it will make the catechism “available to believers all over the world, right in their pocket.” In other words, it will be a “catechist on call.” The app has the celebrated ability to read scripture to the user and also enhances the “beauty” of the catechism by way of added images to each of the catechism questions.

It might be noted, however, that none of these features imply problems with the previously published catechism; they simply improve user ease and efficiency. To Be a Christian was already online as a free pdf, with its own webpage, and therefore available on all smartphones. What problem with its previous universal accessibility is remedied with the new app? Neil Postman related a humorous anecdote when discussing this question. When recently purchasing a new car, he asked the salesman what problems the advertised power windows and cruise control solved. The answer was, of course, none—they simply make driving easier and more comfortable.

Neil Postman’s first question unveils the unspoken premise of our technological society: having more, having it faster, and having it easier are obvious goods that should be pursued in all areas of life. Our society welcomes uncritically any innovation that offers us these supposedly unqualified goods. But is this premise true? What about the means of achieving these goods? We rarely pause to consider these questions because of the speed of modern life. To apply this analysis: does the fact that the catechism is available to more people, in a faster and easier way to access, negate any consideration of the way in which those results are achieved?

Question #2: Whose problem is it? (i.e. Is it a problem many people are facing or only a few?)

The ACNA Catechesis Task Force has identified that there is a significant problem faced by many parishes: “the Church’s children often show that they’ve been discipled effectively by the surrounding culture.” The report concludes that thus, within the church, there must be a return to “the old paths” of what the ancient church practiced. A few questions are raised when comparing this report to the newly launched app. Would most parents say their children’s lack of catechesis is addressed by an app? Is the secular form of an app in harmony with the ways of the ancient catholic Church?

Question #3: What new problems will be created because of solving an old one?

Of the seven questions Neil Postman lays out, this is perhaps one of the least commonly considered before adopting new technologies. If a particular innovation satisfies our modern technological creed (more, faster, and easier), we are often completely blind to issues it will cause. For example, there is rapidly emerging research that smartphone usage is detrimental to children. Is it wise to direct families toward increased smartphone usage by making catechetical programs require such devices?

It is unanimously recognized that smartphone usage is too high. We are constantly lamenting our addiction to screens and our incessant use of them. How will placing the Church’s catechesis app on our home screen help? Will it aid temperance or be a justification for further inattention? A book has one use—it will not suggest I look at a recent text message, email, or news headline while reading. By contrast a smartphone’s use is seemingly infinite. Can the faithful diligently attend to the highest truths of Christ’s Church within such a distracting form? Does it not inherently incline them away from careful reading and devotion?

Another resulting problem will be the perception that catechesis, like all things in modernity, is fluid and ever-changing. A book in your hands has a clear beginning and end, it has limited content. It cannot be “synced” with new content without your knowledge. An app, in its very form, is unsolidified. It is subject to recurring “refreshes” and “updates.” It is already reported that there are plans to add more content to the catechism app, such as a video library. How will the form of a catechism constantly updating affect the faithful’s perception of the faith once delivered to the saints?

Finally, apps are inherently individualistic, for private use. However, ecclesial or familial catechesis is communal—there is catechist and catechumen. By creating a digital “catechist,” the relational and imitative nature of catechesis is lost, and it becomes instead mere information to be individually consumed. How will this tension change the way the Church understands catechesis? We will return to this problem in a later question.

Question #4: Which people or institutions will be most harmed?

In his lecture, Neil Postman pointed out that by spending hundreds of millions of dollars on installing the internet in classrooms, teachers would not receive funding in other needed areas. A similar concern can be expressed here. By turning its attention and funding to mass digital technologies, what local parochial needs will not be addressed that could have been? How many ACNA parishes could have been stocked with copies of the catechism? What about Christian book publishers that could have benefited from partnerships with the ACNA to print cheap copies of To Be a Christian?

Question #5: What changes in language are being promoted?

This is one of the most devious results of modern digital technologies. Neil Postman discussed the change in the meaning of “relationships” in the digital age. No longer does friendship, for example, include the body (or even personhood in the case of artificial intelligence) as an essential component. My “friendship” can be entirely “online” and yet we use the same word to describe it as a natural, embodied relationship. This doesn’t merely cheapen our words, it modifies them, in a profoundly disincarnating manner.

What will be the result of having a digital app as a “catechist?” As our language becomes disembodied, so will our catechesis. No longer do I open a physical book or listen to an embodied person read scripture—let alone find the references in my printed bible! A fundamental question is being raised: can materiality be cast off quickly in the name of more, faster, and easier? That argument has not been explicitly made in our culture amidst the rapid pace of technological change; but the answer is woven into the digital technologies we use each day. For those named by and joined to the incarnate Lord, confessing Christ’s unity to substantial matter each day, it ought to be a serious concern.

Question #6: What shifts in economic or political power are being promoted?

This question may not appear relevant to a catechesis app. But technologies cannot be considered in isolation from the institutions and historical circumstances they arise in. What potential dangers are there in tethering the faithful’s catechesis to Apple or Google? Is it wise for the Church to depend on and fund such companies? Technologies begin as tools and end often as replacements. If the future of Christian catechesis is digital, what economic institutions will the church have to submit to in order to achieve it?

Question #7: What alternative uses might be made from a technology?

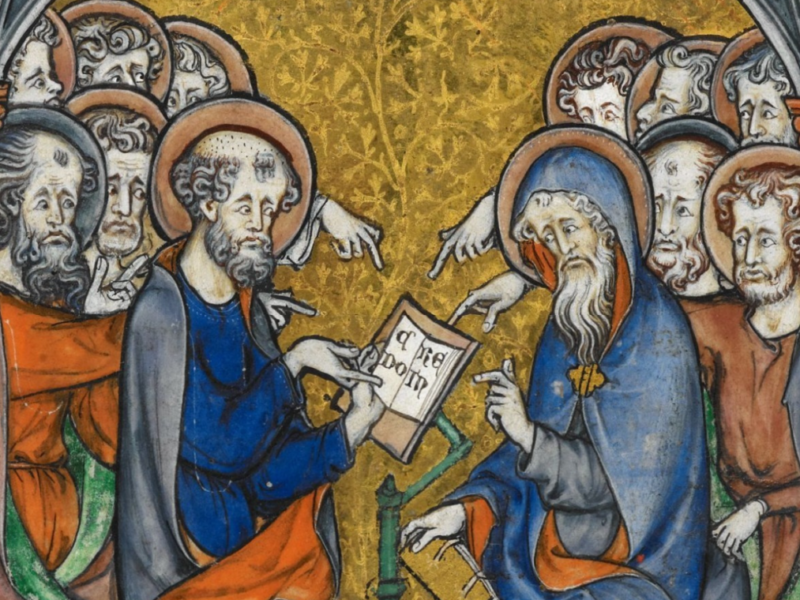

This final question returns to an earlier concern about the form of a digital app. If the catechism, previously a physical book exposited by a living and present person, is now a centralized, digital app, what can now be inserted into the catechism? The catechism app has already added images to accompany each of the 368 questions. How does this addition of a visual medium, in a modernist style, change the catechism? What does it communicate about Holy Scripture and sacred tradition?

Conclusion

Neil Postman’s seven questions help begin a sober assessment of the impact of a new technology. We must ask these questions because we ought not to blindly follow more, faster, and easier. The Christian conviction is that all of creation, with its limits, graciously leads us to God. Technology always grants greater power; but it can do so in harmony with the divine or against it. Our chief end is to humbly receive reality in the manner God has graciously ordered it, not to pursue technological progress.

None of this analysis is meant to impugn the motives of those who advocate for the app. The dogmas of the technological society so easily penetrate our thinking that it is foreign to consider such questions. We are often not conscious of how modern technology has shaped our very presuppositions about itself. In our technological milieu Neil Postman’s questions seem strange and antiquarian. But if we reflect on the fact that Neil Postman’s example in 1997 of a new technology was vehicle cruise control, we can begin to see the scope of drastic change that has occurred since the turn of the millennia. That change will only continue to radically accelerate in coming years, increasing pressure on the church to accept novel digital mediums and forms.

If we do not begin to cast a prayerful, critical eye on modern technologies we will have no hope of raising our children to remain in the truth of Christ’s Church. For we send them undiscerning into a world of technologies promising them more, faster, and easier. Our children will be incapable of distinguishing which are in harmony with God’s order, and which are diabolical perversions of it. The false gods of technological progress and efficiency daily extend their conquest over more and more embodied goods—often without a single question or challenge. May the Church not accommodate herself to these gods of the technological age.

Image Credit: Unsplash