Introduction

By presenting the work of contemporary scholarship and engaging in literary criticism, this essay will explain the nuanced and robust ecclesiology demonstrated across Matthew’s gospel and Luke-Acts. The scope of the essay will discuss in detail how each piece of literature demonstrates the church as the local community, as the institutional continuation of Christ’s ministry, and as the cosmic, mystical, and sacramental connection to Christ found in the collective of each individual Christian.

The Ekklēsia and The Kingdom of God

A resounding theme in Matthew’s gospel is the “kingdom of heaven.”[1] Typical analyses of Matthew’s gospel treat these terms as references to fulfillment of prophecy or future eschatological fulfillment, each being Messianic. An alternative yet harmonious lens through which one could view Matthew’s theology of the kingdom is by looking at Christ’s incarnation, person, ministry, sacrificial death, and resurrection as the locus of the term itself.

Nearly immediately after he introduces Jesus into the narrative, Matthew shows John the Baptist, traditionally understood as the forerunner to Christ, proclaiming repentance and declaring that the kingdom is at hand (Matt. 3:2). In Matthew’s gospel, it seems clear that what John means by “the kingdom is at hand” is that the one he was prophesied to prepare the way for is approaching.[2] In the same manner, later on, Matthew records Christ proclaiming repentance for the coming of the kingdom (Matt. 4:17), leading the reader to believe that Matthew doesn’t exactly mean to refer to the person of Christ literally but rather associates the person of Christ and the assumption of his fulfilled mission as one and the same, holding equal importance. Matthew associates the king and kingdom as effectively united.

In conjunction with the rest of his gospel, it would appear that Matthew means to proclaim that, in the person of Christ, the redemption of the world is approaching, demanding repentance not just from the far-off Gentiles but also the lost sheep of the house of Israel (10:5–7). In relation to this redemption, both Matthew and Luke record Jesus declaring that God can raise up children of Abraham from stones (Matt. 3:9, Luke 3:7–10), indicating a greater concern with genuine repentance and belief than ethnic or national identity. If the coming kingdom is, at least in one sense, this fulfillment or redemption appropriated by the person of Christ, there is another sense in which the church can be understood as the kingdom.

If Matthew sees Jesus and his purpose as the “coming kingdom,” then one must consider the possibility that Matthew intended his audience to understand this coming kingdom not merely in a narrative sense but in a real way that applied to their own lives even then, after the crucifixion. The significance of a radical multi-ethnic redemption is lost if the post-Christ audience cannot apprehend it. This is where one might begin to read between the lines in terms of ecclesiology. Matthew’s demonstrated theology of the church is not merely a collective that follows Jesus’ way of life or the “law of Christ” in an individual or isolated manner. Of course, the beatitudes (Matt. 5-7) could essentially be read as Jesus’ manual for Christian life,[3] applying to then and now as well as after his death.[4] Jesus’ declaration that he has not come to abolish the law but to fulfill it (5:17) could be interpreted in a similar way. Yet Matthew demonstrates that he understands the church as more than just a gathering of individual people centered around a common set of culturally subversive lifestyle choices.

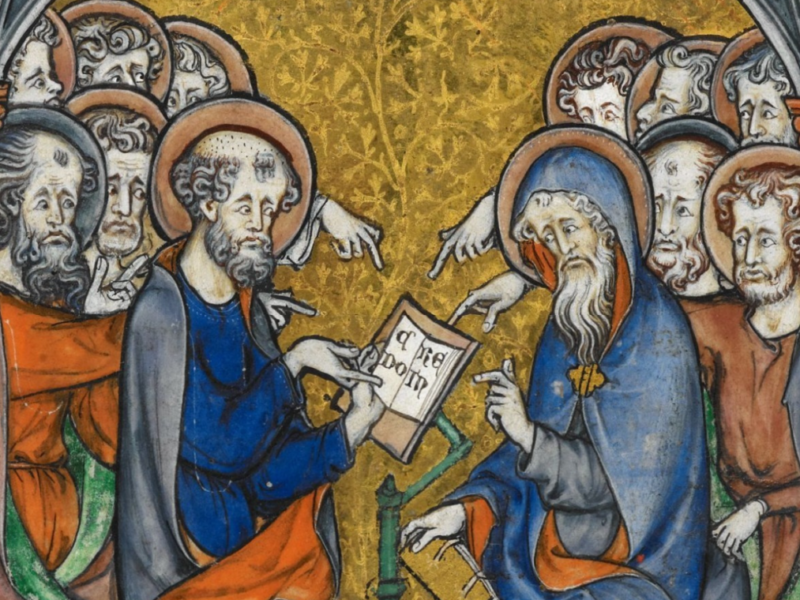

Matthew uses the term commonly translated as “church” (ekklēsia) only twice (16:18–20 and 18:15–19), and both usages are attributed to Jesus, particularly during what could be referred to as the institution passages. Despite Matthew’s distinctly Jewish background, the usage of ekklēsia indicates somewhat of a break from Old Testament language (according to the LXX), referring to places of worship or gatherings of the people of God (synagōgē).[5] While in some cases ekklēsia is understood as generally referring to an assembly or gathering of people for a certain purpose (and thus similar to synagōgē),[6] both the Septuagint and classic Greek literature often use the term with special significance to a cultic or civic kind of assembly, one that holds more significance than individuals gathered together.[7]

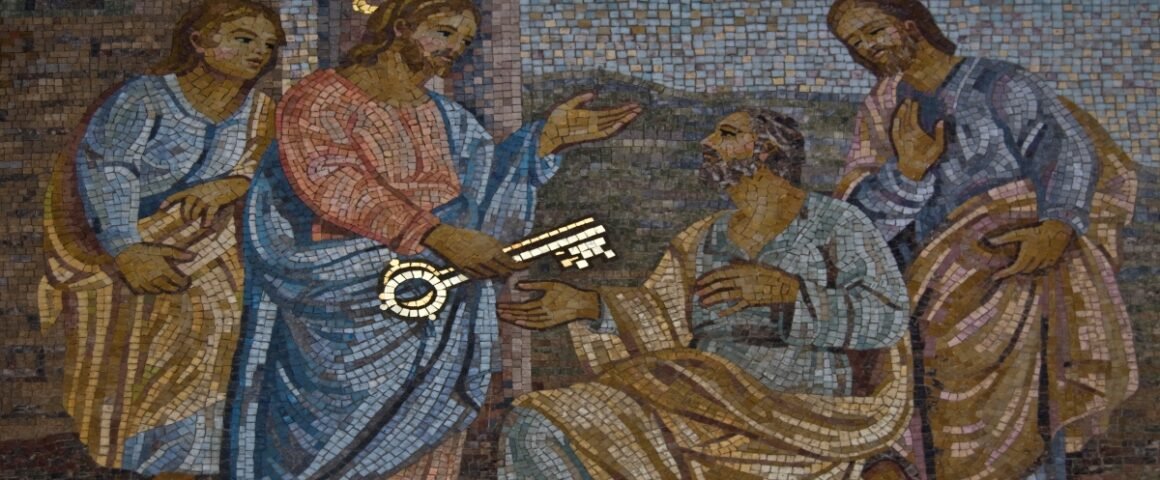

In these passages, Jesus gives an incredibly noteworthy kind of authority, initially to Peter and then corporately to the twelve. In both chapters sixteen and eighteen, Jesus says he is granting them the authority to “bind and loose.” In chapter sixteen, Jesus grants Peter this authority after his confession of Christ as the Messiah (16:16), saying, “on this foundation” he will build his ekklēsia, specifically connecting it to handing Peter the keys to “the kingdom.” [8] It is here that one could find a connection between Matthew’s theology of the kingdom and his ecclesiology. In chapter eighteen, Jesus discusses the idea of an unrepentant person in the church (continuing in the terms he has established two chapters previously) and brings up the aforementioned binding and loosing in the context of excommunication. He raises the stakes of this authority from a purely communal, material decision to a transcendent and spiritual one, saying that when the apostles decide something, “it will be done by my Father in heaven” (18:19). The power granted here isn’t just the ability to speak authoritatively to the community in a moralistic sense, but a more extensive kind of authority with divine ratification.

In chapter ten, Jesus gives the twelve authority over unclean spirits and to cure sickness, and then he sends them out to participate in his ministry (10:5–9). As part of his instructions to them, he commissions them as ambassadors, saying that whoever welcomes the twelve welcomes him (10:40), recalling a rabbinic principle of representative roles.[9] Though not found in Matthew’s narrative, cross-referencing John’s gospel adds supplemental value to this particular study of the kingdom. John records Jesus breathing the Holy Spirit on the apostles and giving them the authority to forgive and retain sins (John 20:22). Jesus isn’t just giving the apostles merely material authority; he is giving them the same authority he claims as his own as the Son of God. Thus, Matthew fleshes out his theology of the kingdom of God as something distinctly connected to the ekklēsia.[10]

This passing on of spiritual authority to the apostles is not an arbitrary choice. Luke’s gospel gives us a unique view of the importance of bearing the apostolic ministry, recording that Christ spent all night praying over what disciples he would select to become “the twelve” (Luke 6:12–16). The number of apostles was also not arbitrary; it was to fulfill the complete restoration of Israel, showing that the apostles are symbolically connected to the twelve tribes of Israel, so much so that Jesus promised them twelve thrones alongside his glorious throne, to judge the tribes of Israel (Matthew 19:28).[11]

Right after the second “binding and loosing” section in Matthew 18, Jesus tells the apostles that wherever two or three of them are gathered, he is there with them. This is later fleshed out and attached to the mandate of making disciples, teaching, and baptizing (the sacramental rite of entrance into the ekklēsia, and thus the kingdom) in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,[12] giving them the full commission to, in a sense, be Christ to the world.

This could be seen, in a sense, as an earthly extension of the kingdom, the institution through which Christ promises his perpetual presence in the life of the believer and the world. The gospels of Matthew and Luke demonstrate vividly that Christ continues on his ministry, even opening access to the kingdom, particularly through the apostles as the foundation of the church (Ephesians 3:20).

Ekklēsia as Community in Acts

The book of Acts gives us the best picture of the church as the local community of believers in the whole New Testament as people empowered by the Holy Spirit.[13] Luke shows us a gathering of followers celebrating the sacraments of baptism (2:38), eucharist and prayer (2:42b), devoting themselves to the teaching of the apostles (2:42a), holding everything in common (2:44–45), meeting regularly (2:46–47) and engaging in regular evangelistic mission to further include both Jews and Gentiles in the kingdom of God (Acts 11:18).

From the very beginning of Acts, Luke parallels both his own gospel writing and Matthew’s by describing Christ as the one who baptizes with Spirit and fire (Acts 1:4–5, Matt. 3:11, Luke 3:15–17), in contrast to the baptism of John, who proclaims the coming of the kingdom. In multiple places throughout the text, Luke presents a picture of the baptismal rite as attached to repentance and forgiveness of sins but is found distinctly in the context of the ekklēsia. Luke demonstrates that the baptism of Christ, that baptism of Spirit and fire, is the distinct entrance rite into the ekklēsia, the church that is communal (local and mystical) yet located in the authoritative institution laid on the foundation of the apostles.

Continuation of Apostolic Ministry Through the Episkopos

Luke records Peter expositing Psalm 69 to a group of believers that it was prophetically necessary for Judas, who shared in the apostolic ministry, to betray Christ and reap the reward of wickedness (Acts 1:12–21). Peter then emphasizes that someone else must take his “office” (1:15–20, ESV).[14] The word translated as “office” in the ESV is a variation of the Greek word ἐπίσκοπος, episcopos.[15] This is particularly interesting because the term is only used in this form five times in the entire New Testament, three of which are used in the pastoral epistles to refer to the overseer (bishop, etc.) of a congregation.[16] It should be noted that the word used to refer to the office of an apostle (through whose derivative authority the church is governed)[17] is a variation of the term used for bishops throughout the New Testament, not necessarily suggesting a causal relationship, but could be significant.

Luke records Matthias’ replacement of Judas as an apostle. Matthias is not merely elected to a pragmatic role but inherits the same kind of apostolic authority of the twelve, likewise fulfilling the symbolic picture of the number twelve that Jesus sets forward.[18] In this way, the book of Acts demonstrates that Christ instituted and gave authority to his ekklēsia not only for a temporary period relegated to the 1st century but for all time.

Conclusion

The gospels of Matthew and Luke, as well as the Acts of the Apostles, paint a careful picture of the ekklēsia as the authoritative institution of Christ that holds the keys to the kingdom, possessing the derivative authority to bind and loose and perpetuate Jesus’ ministry. Yet these texts also present a clear idea of the church as the local community that participates in corporate worship, which connects all followers of the Lord despite race, background, geographical area, and all other factors.

Notes

[1] This is often understood as synonymous with “kingdom of God.” See T. K. Dunn, Prophet Priest, Prince and the Already, Not-Yet (Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications, 2022) for a modern discussion on the issue.

[2] Luke also informs us of John’s preaching of repentance (Luke 3:3) but leaves out the “kingdom” idea.

[3] Perhaps even a manual on expected conduct for the citizens of this coming kingdom.

[4] R. E. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament Anchor Bible, 1st ed. (New York, NY: Bantam Doubleday Dell, 1997), 178.

[5] Daniel J. Harrington, The Gospel of Matthew (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1991), 251.

[6] In classic Greek literature, this term could have been understood as referring to the assembly of all the people in a city—a town hall of sorts. The assembly would begin with prayers and sacrifices to the gods and eventually move into more pragmatic issues in which each member of the society could use their voice. Whether or not it was followed was a different matter; there was at least an illusion of democratic decision. Thus, before the writing of the New Testament, Greeks would have understood the term as referring to a mix of the political and cultic. The LXX uses the term somewhat sparingly (100 times, 22 being apocryphal) and is quite careful not to use the term in any way that maintains the same political or cultic meaning that the Greeks associated the term with. The Hebrew term it is translated from often means a religious or solemn assembly and is often used simply for the gathering of the military. It is more flexible and somewhat ambiguous in this context. Most often, it is translated to refer to a general assembly of the people or a judicial assembly of some kind. In the New Testament, as has been demonstrated already, the term is almost completely unused in the gospels except for the two passages from Matthew’s gospel. Luke uses the term over 20 times in Acts. Paul completely transforms the use of the term to broaden it to a cosmic scope.

[7] Colin Brown and Lothar Coenen, The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1986), 1:291–96.

[8] Scholarship also varies greatly as to whether “rock” refers exclusively to Peter himself, the collective of the apostles, or Peter’s confession of faith in Jesus as the Christ.

[9] Brown and Coenen, New Testament Theology, 1:151.

[10] Not in the sense that the ekklēsia holds this connection in and of itself, but the church holds it because it is derivative from Christ.

[11] Luke T. Johnson, The Gospel of Luke, Sacra Pagina Series, ed. Daniel J. Harrington (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2006), 3:103.

[12] Likely the baptism that John the Baptist prophecies; the baptism of spirit and fire as mentioned in Luke 3:15–17 and Matthew 3:11.

[13] See Acts 2:1–13, 2:37–47, 4:2, 7:32, 5:41, 6:1–6, 9:31, 13:50–52, 16:14–15.

[14] Luke T. Johnson, The Acts of the Apostles, ed. Daniel J. Harrington (Collegeville, MI: Liturgical Press 2008), 38.

[15] The typical form of the word is often translated as “bishop” or “overseer.” There is instruction given to those who are episkopos throughout the pastoral epistles as well as qualifications for the character of those who will receive the laying on of hands and be ordained in the “ekklesia of God,” as Paul would say.

[16] Both the LXX and classic Greek literature use the term to refer to somebody with a significant level of power or authority. See Brown and Coenen, 188–89.

[17] In 1 Peter 2:25, Peter refers to Christ as the “episkopos of your souls,” further implying a kind of connection between the authority of Christ and that which is passed down to those he chooses, or the eπίσκοπος. For more on this, see Bock, 376.

[18] Johnson, The Acts of the Apostles, 38–39.