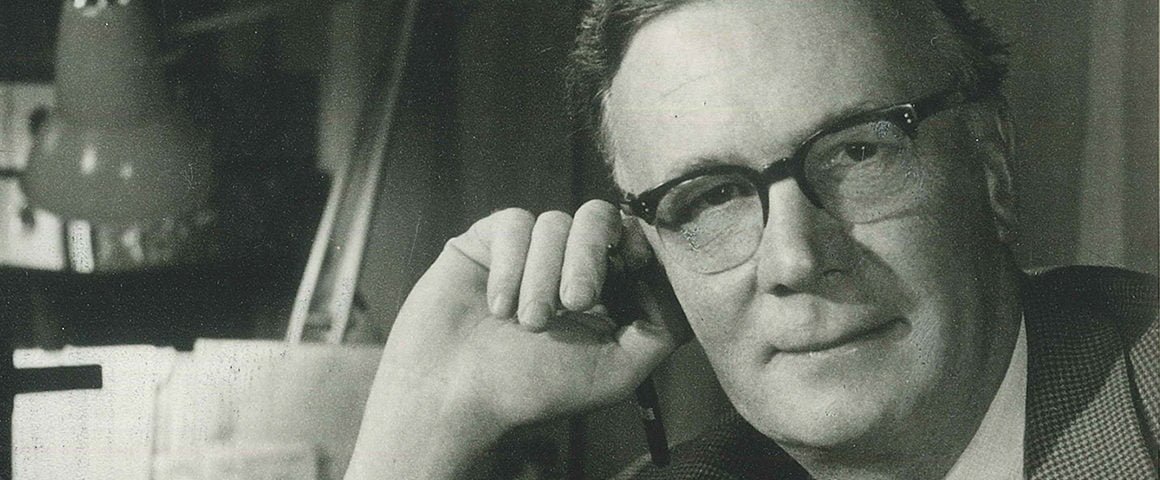

Few Christian authors in the second half of the last century had such broad influence inside and out of the Church as J. B. Phillips. Phillips, a Church of England parish priest, became the most famous Anglican clergyman of his day, on both sides of the Atlantic. A contemporary of C. S. Lewis (who encouraged his translation work), Phillips wrote in the main for the “plain man” (and woman)—the person without theological training who may or may not have had a literal or figurative baptism into the Christian faith by growing up within a parish. His writings all have a common-sense approach and tone that set them apart from other Christian writings of the day (and, one could argue, since then as well).

His most important work was his translation of the New Testament into colloquial English, written initially for the young people in his parish. His fresh and winsome translation became The New Testament in Modern English—known by many since as, simply, Phillips. But he wrote many other popular books, including the Christian classic, Your God is Too Small, which (like his New Testament) remains in print. All together his books have sold many millions of copies.

Phillips also became known for having suffered from sometimes debilitating depression—and for speaking in then-atypically frank terms about it. It is likely the emotional intelligence and keen understanding of the human condition evident in his writings reflect that challenge in his life.

Phillips’s grandson Peter Croft has undertaken through the J. B. Phillips Society to bring renewed attention to this modern giant of the Christian and Anglican world, with the larger aim (in his words) “to invigorate many to delight and trust in the scriptures and live lives full of passion for Jesus” and with hopes “to see this generation profoundly changed by a living experience with the world-changing, exciting, raw power of the scriptures.”

I last month interviewed Mr. Croft (whose fine concise biography of his grandfather can be found here). We discussed the life, impact, and relevance of J. B. Phillips, now 90 years after his ordination and almost 60 years after the publication of his revised New Testament in Modern English.

N.B. Emphases in the text following were added by Mr. Croft.

AW: Peter, thank you for taking time to discuss J. B. Phillips.

PC: It’s my pleasure.

AW: Your grandfather died before you were born. When did you realize your grandfather had been one of the 20th century’s most important Christian figures–and how did that happen?

PC: Yes, he died in 1982, the year before I was born, so I just missed out. I have had a hardback copy of the New Testament in Modern English for many years. Indeed, it still has my six-year-old handwriting inside it saying, “Grandad wrote this Bible.” My mother, his only child, died when I was 11 years old, at which point I had not yet come to understand the Gospel for myself.

AW: What changed?

PC: Some time in my mid-teens I heard the Good News and made a commitment to follow Jesus. Since then, and especially after moving to the United States a few years ago, I have met a broad range of people who have told me personal stories of the impact of my grandfather’s work on their lives. For many of them it was J. B. Phillips’s version of the New Testament that was the first scripture available to them that they could fully understand and that led them to faith in God. For others it was the powerful messages of his non-translation books which led them to completely reassess their view of God and as a result come to know him and his purposes with greater clarity.

A few years ago in Uganda, I met a distinguished older American gentleman who pressed on me strongly that J. B. Phillips was among the most influential Christian leaders of the 20th century. Most of the people I have met have been over the age of 60 or so, but in the last year or so I have become aware of Phillips’s influence on a growing number of younger people – in fact one such person has been so impacted by J. B. Phillips that he was a wife’s veto away from naming his son Phillips!

Mentions of J. B. Phillips in books, sermons, podcasts and articles have been passed on to me by friends, and I have come across a number myself, including several references within the works of John Stott, Eugene Peterson, Tim Keller and other prominent Christian leaders. It has been incredible to learn that not only in my close lineage was a faithful man of God, but that this same man undeniably altered the lives and destinies of millions of people. Over the past several years I have read the published works of J. B. Phillips for myself and his legacy has now extended to me.

AW: If you had to identify one thing that made J. B. Phillips so powerful in his influence, what would that be?

PC: The most consistent feedback from the Phillips version I have heard from others is that he makes the scriptures feel alive. The person of Jesus walks off the pages, the vigor of the young church seems tangible, the eternal dimension we so often miss in the day-to-day becomes real. He successfully manages to reflect his experience of translating it—it was as if the fresh air of heaven blew gustily through its pages.

AW: J. B. Phillips was a simple Anglican priest. But quickly he became—and for two or three decades remained—the most famous Anglican clergyman, certainly in Britain and North America. How did he handle what must have been a somewhat unexpected change of this sort?

PC: I think at first that he liked it. He was from a young age driven harshly by his father, who recognized his intelligence, and as a result wanted to be so perfect that he was above criticism. Even though he had no lofty goals, the attention must have been welcome relief to the demands of perfectionism. Later it is clear that he took seriously the responsibility that his profile carried with it. He received thousands upon thousands of letters from all corners of the globe, and after assuming many of them may not have a local pastor locally, responded to them all. He talked about how his parish became the world. Some of the attention was odd to him – there is a chapter in his autobiography, The Price of Success, which talks about his first American tour and how one of the church services he led in Hollywood was televised, and also how people travelled thousands of miles to hear him at a retreat. To me there is almost a contradiction—he was clearly upset at one point not to be valued more by his own denomination, but at other times he could not understand why people would give him the attention he received.

AW: His work began with his translation of the New Testament—and one could say that his New Testament is his most lasting legacy, available still as it is today in print and online. Remind us how this came about. And give us a sense of how profound the effect of this undertaking was.

PC: He met regularly throughout the war with a youth group at his church known as the “King’s Own.” They kept themselves busy with various fun activities. At the end of each meeting, J. B. would read scripture to encourage them in their situation, often reading from the letters of St Paul. He read from the King James Version, known commonly as the Authorized Version. This was the Bible translation of the time.

However majestic much of its language is, it was not intelligible to the young folk who attended the King’s Own. It was like a different language. He came to be disturbed by the blank faces that met his gaze as he read scripture to them and realized that if there was any chance of these young people understanding the Holy Scriptures, let alone seeing any relevance in them, there would have to be a new, modern translation.

Since he had no other option, he started translating himself. He remembers it this way: “all my old passion for making truth comprehensible, and all my desire to do a bit of real translation, urged me to put some relevant New Testament truths into language which these young people could understand.” He started with Paul’s letter to the Colossians. The response was beyond his expectations. These young people heard the words in a way they could understand and quickly came to appreciate that not only could scripture make sense but was also extremely relevant to their lives. It even started to change them.

AW: How did this translation project for a small group of young people in his parish become something so much larger?

PC: Encouraged by the effect of his translation on his youth group, in 1943 he wrote to C. S. Lewis, whose work he had long admired. In the letter, he included a copy of his translation of the book of Colossians. Lewis wrote back saying, “thank you a hundred times. . . it was like seeing an old picture after it’s been cleaned.” And Lewis encouraged him to carry on. Eventually, J. B. finished translating all the New Testament letters, which were published as Letters to Young Churches—C. S. Lewis’s suggested title.

Over the next few years, he was asked to translate the Acts of the Apostles—which he called The Young Church in Action—and then The Book of Revelation, and finally The Gospels. A combined volume was released as the New Testament in Modern English in 1958. It really struck a chord—to this day I hear from people who tell me his translation was the first time they understood the scriptures. It is hard to remember that in the 1940s and 1950s, there were so few translations available and even today there are very few with such vigor and energy. Along with his translations, he wrote 26 books and by my estimate they sold at least 12 million copies.

AW: Probably his most famous turn of phrase from his New Testament was Romans 12:2. In the King James that read, “Be not conformed to this world.” He renders it, “Don’t let the world around you squeeze you into its mould,” which captures exactly what Paul is trying to say. What are your favorite turns of phrase from his New Testament?

PC: For me, it is more about the general flow and elegant simplicity of the translation that appeals. As I read, I find myself “there” in a sense, and the passage becomes clear in its meaning. It feels alive. J. B. Phillips wanted his translation to evoke the same emotions as those listening or reading in the first century. He also worked very hard at mirroring the particular styles of the authors, from the unsophisticated, rushed tones of Mark to the high Greek of Luke. He felt something was missing in the admitted beauty of the King James. Having said that there are a few specific phrases and spring to mind.

I never understood, for example, “weeping and gnashing of teeth” as a phrase to describe some of the realities of hell. Phillips’s “tears and bitter regret” is more helpful. Famous phrases such as the one you mentioned from Romans are quoted in books and sermons to this day. These wonderful translations get to the real essence of the message the writers were attempting originally to convey. I love his translation of the beatitudes in Matthew 5.

AW: This plainly excites you as a believer who loves Scripture. What are some others?

PC: There are many more, but here are a few more that I like specifically:

“These are the men who have turned the world upside down”—from Acts 17:6b, in Thessalonica.

And from 1 Peter 5:7:

“You can throw the whole weight of your anxieties upon him, for you are his personal concern.”

My grandmother—J. B. Phillips’s wife–wrote this inside the copy of the Phillips New Testament she gave me at my baptism and confirmation in the Church of England, so this—Romans 8:18,19—is always a favorite for me:

“In my opinion whatever we may have to go through now is less than nothing compared with the magnificent future God has in store for us. The whole creation is on tiptoe to see the wonderful sight of the sons of God coming into their own.”

AW: Tell us more about C. S. Lewis’s role in helping your grandfather. How would you describe his writings in comparison to those of Lewis?

PC: Lewis’s first letter to J. B. Phillips was a great encouragement to him. It’s probably worth me putting the text of the whole letter up on the J. B. Phillips website in the blog section at some point soon.

It gave him the boost, I think, to endure the rejections that were to come his way. He wrote to many publishers, all of whom rejected the idea and the sample. And it was Lewis who paved the way for a meeting with Geoffrey Bles, Lewis’s publisher, who eventually agreed to publish. C. S. Lewis wrote the introduction to that first book—which is on the blog—to that first translation, and suggested the title Letters to Young Churches, for his translation of the epistles. He also commented on several of J. B. Phillips’s books, and those comments were included on the sleeves of some editions.

I have no doubt that Phillips would not compare himself to the genius of Lewis, but it was said quite widely, I understand, that many people saw him as the successor to Lewis—by this time Lewis was past his peak. Indeed, recently I was in contact with Lewis’s secretary, and he told me Lewis loved all of J. B. Phillips’s books. I have heard and read from others that Lewis himself saw Phillips as his successor.

And, of course, there is the vision he had of Lewis shortly after Lewis died, which is quite fascinating and worth a read, either in The Price of Success or in my own short biography on the website.

To me, they both had the gift of explaining complex and abstract thoughts in simple terms and describing things in fresh ways. Lewis and Phillips were not like most of us–they could recognize the extraordinary quality of the early documents and the figures that walked off the pages and could describe them powerfully in contemporary terms and with great energy where one is left excited about familiar themes.

AW: Did your grandfather’s publishers see this kinship and connection between the two?

PC: Guy Brown was Macmillan religious editor at the time and wrote this letter upon his retirement—permit me to read it, because I think it is quite powerful and very much goes to the question you asked, as well as to his influence in America. Brown writes:

I have saved this letter as one of my very last official acts as the director of religious books department of Macmillan. This has been done deliberately so that I could end my eleven years of service with the greatest tribute that can be paid to any of my authors. No-one of my authors has won the affection of the American public as has J. B. Phillips. His publications have without exception won their way into the hearts and lives of countless thousands of Americans. No one dare predict how many lives have been enriched by his published works. Hundreds of letters attest to that fact, and surely there are thousands of his admirers who may not put their sentiments into these letters of appreciation that they most certainly feel. Sufficient evidence is in hand to confirm that J. B. Phillips has brought about a revolutionary change for good in the lives of the countless thousands of his American readers. He has communicated, in a new and vital manner that has had no peer since the early days of C. S. Lewis. Indeed I am firmly convinced that the writings of J. B. Phillips are more significant in the American religious scene than those of any other single British author. Indeed he may very well be the most influential writer of popular religious non-fiction in the English-speaking world today.

AW: Do you see parallels to where we find ourselves today as a church, society, and culture that would commend his books?

PC: There are classics like God our Contemporary, which, though written in a different time—the dawn of the nuclear age—still resonates today, in this changing and fearful world.

But above all I would say that the themes of all his works which I think I am right in identifying, are still blind spots for many Christians and inhibit our ability to live fully as sons of God. Do we really understand who Jesus is, the beauty of his life and the revolution he began and we are part of today? Are we clear on our purpose here on earth as ministers of reconciliation? Do we really believe the full resources of God are fully available to us just as they were in the first century? Do we experience the living quality and unique-ness of scripture?

I think the answer in this busy and distracting world, is “no” for many of us. Phillips somehow helps us cut through the clutter and get to the essential message, and what we get when he does that is this beautiful, powerful, life-shifting, exciting and dangerous way of living which was the early church and can be experienced today. This is an age-old problem. Some of us have a fire inside us to get back to what it is really all about. Phillips gives us a framework and a vocabulary and a context for eternal truths to shine through—all, as he would freely admit, nothing new, but taken straight from his electrifying experience of scripture.

AW: Other than his New Testament, what are your favorites of your grandfather’s books, and why?

PC: It changes for me. In the past year or so I have really found a lot in New Testament Christianity, which is not one of his best-known books. I decided to record it and put it on Audible and Amazon to get it out there again. I love Making Men Whole, When God Was Man and of course classics like Ring of Truth and Your God is Too Small. He had some good titles, did he not?

AW: He certainly did, and I suspect those titles led many people to read his books. What one book of his would you recommend for someone not yet familiar with him?

PC: I think New Testament Christianity is a great place to start for someone who is a believer. It strips the reader of possible over-familiarity to the true danger and excitement of the gospel message.

AW: Your God Is Too Small was his most popular book and has remained in print. I have recommended it to many friends and it was among a group of Christian classics books I gave my eldest son to read during his college years. What do you think accounts for its apparent timelessness?

PC: Your God is too Small does something similar to New Testament Christianity and is also an approachable book for the skeptic. We all need to challenge our view of God. If we do not have a true understanding of who God is, he will never command our allegiance or excite us to follow Him. The book helpfully suggests some baggage we inevitably bring to our picture of God and challenges us to really look deeply at who scripture says he is.

The way he does it is simple—the documents are there to see for ourselves, but what I think is so unique about it is that, saturated over so many years of being in the original Greek text, is that he could see so clearly the beauty and power of God and as such could point out the stark contrast between so many people’s views of God and the reality of His being. And of course, his always beautiful and simple language helps move us forward towards that reality better than most.

AW: Your grandfather wrote for a broad audience, both Christians and those seeking or skeptical about Christianity. Undoubtedly his Anglicanism comes through, but rarely is he explicit about it. Are any of his books ones that would have particular resonance with orthodox Anglicans?

PC: Because he was so well known and met so many people through his broadcasting and correspondence, he came into contact with people from many denominations and was greatly encouraged by the common ground that exists. He seemed surprised by that. So that it itself is an encouragement to Anglicans to get out there and build friendships with other churches, if possible. And you are right that he was not explicit about Anglicanism, though he does mention familiar concepts to Anglicans like “the communion of saints” from the Creed when, for example, referring to his supernatural visit from C. S. Lewis.. Anglicans may benefit from reading Appointment with God, which is a short, fresh look at communion, with thoughts often overlooked by many of us.

AW: Those who know the life story of your grandfather know he suffered off and on from deep depression, depression he traced to his challenging relationship with his father and a sense from that he had to be perfect or would be a failure. How did this struggle affect and inform his writings and his ministry?

PC: I gather from listening to talks by my grandmother, his wife, that it made him very sensitive to the feelings of others. I get the impression he was very empathetic. It also made him humble: if you read The Price of Success you may get the impression as I did that here was a man greatly used by God and yet not the finished article that we want our heroes to be. I think that is important from what I have seen in American church circles—we should be careful not to put people on a pedestal. He is still one of my all-time heroes, by the way—but I am also careful to “trust not in princes.”

He was quite open about his struggles which I think is an example to us all. England is not a place known for vulnerability—“stiff upper lip” and all that. Certainly not then. It is only the past few years that the culture has changed to where mental health is being spoken about openly. He was way ahead of his time, and I think gave permission for others to articulate their struggles. That is huge. And, of course, he had the skill to be able to do that on behalf of others—many people wrote to him and thanked him for his descriptions—they were exactly what they felt but were not able to put those feelings into words before.

AW: Many of the North American Anglican’s readers are Anglican clergy. As a last word for our time together, what lessons does J. B. Phillips offer them from his life and ministry?

I think a few things. Know Jesus. Fall in love with his true character. Present the scriptures in their raw form. Let the Word do the work. The J. B. Phillips Society we set up is not about Phillips really at all: it is about what God did through him. If every priest, vicar, rector or curate could learn anything from his life and ministry I would love them to experience, regularly, the raw, unchanging, livingness of Holy Scripture.

I would urge every bishop, priest, and deacon to read and reflect on this wonderful extract from Making Men Whole which beautifully explains the incredible honor and task of any communicator of the gospel. As usual, J. B. Phillips brings fresh clarity and freshness to things that are easily passed over.

The work of the pastor of human souls is a vocation about which I naturally know rather more. And here, if we are as Christ was, “gentle and humble in heart” (St. Matthew xi. 29) the cost is often high. To listen patiently, to use skillfully imaginative sympathy, to advise wisely—these things all carry something of the price of redemption. Those of us who try not only to sort out human muddles but to strip away misconceptions and prejudices which prevent the soul from seeing its God, know that we have a work with its own peculiar tears and toil and sweat. The preacher and the writer may seem to have an apparently easy task. At first sight it may seem that they have only to proclaim and declare; but in fact, if their words are to enter men’s hearts and bear fruit, they must be the right words shaped cunningly to pass men’s defences and explode silently and effectually within their minds. This means in practice turning a face of flint towards the easy cliché, the well-worn religious cant and phraseology, dear no doubt to the faithful but utterly meaning less to those outside the fold. It means learning how people are thinking and how they are feeling; it means learning with patience, imagination and ingenuity the way to pierce apathy or blank lack of understanding. I sometimes wonder what hours of prayer and thought lie behind the apparently simple and spontaneous parables of the Gospels. It is not enough for us who are preachers or writers to give an adequate performance before the eyes and ears of our fellow writers and preachers; instead we have the formidable task of reconciling the Word of truth with the thought-forms of a people estranged from God; interpreting without changing or diluting the essential Word. [pp. 75-76]

'Rediscovering J. B. Phillips: An Interview with Peter Croft' have 2 comments

September 15, 2020 @ 8:56 am Cynthia Erlandson

Thank you for this fascinating article! All I’d known about J.B.P. until now was his authorship of the historical introductions in my high school English Literature book (“Adventures in British Literature).

December 26, 2020 @ 10:10 pm Andrew Leask

I will re-read JBP’s NT again with renewed awe and respect. My second NT was this book — second after the AV! My godparents gave me this book at my confirmation 50+ years ago and it is a version I refer to regularly. My mother worshipped in the parish of The Good Shepherd, Lee, London before the Second World War, until she married in St Margaret’s, Lee in 1940. The Good Shepherd was built as a ‘chapel of ease’ for St Margaret’s Lee in 1881.