I’ve been reading Graham Greene’s Orient Express and this passage struck me. In this scene, Dr. Czinner (a Serbian communist revolutionary) has the sudden urge to seek confession and search out the Anglican priest he noticed earlier on the train.

“Dr. Czinner drew the door to and sat in the opposite seat. ‘You are a priest?’ He tried to add ‘father,’ but the word stuck on his tongue; it meant too much. It meant a grey starved face, affection hardening into respect, sacrafice into suscpision of a son grown like an enemy. ‘Not of the Roman persuasion,’ said Mr. Opie. Dr. Czinner was silent for several minutes, uncertain how to word his request. His lips felt dry with a literal thirst for righteousness, which was like a glass of ice-cold water on a table in another man’s room. Mr. Opie seemed aware of his embarrassment and remarked cheerfully, ‘I am making a little anthology.’ Dr. Czinner repeated mechanically, ‘Anthology?’

‘Yes,’ said Mr. Opie, ‘a spiritual anthology for the lay mind, something to take the place in the English church of the Roman books of contemplation.’ His thin white hand stroked the black was-leather cover of his notebook. ‘But I intend to strike deeper. The Roman book are, what shall I say? Too exclusively religious. I want mine to meet all the circumstances of everyday life. Are you a cricketer?’

The question took Dr. Czinner by surprise; he had again in memory been kneeling in darkness, making his act of contrition. ‘No,’ he said, ‘no.’

‘Never mind. You will understand what I mean. Suppose that you are the last man in; you have put on your pads; eight wickets have fallen; fifty runs must be made; you wonder whether the responsibility will fall upon you. You will get no strength for that crisis from any of the usual books of contemplation; you may indeed be a little suspicious of religion. I aim at supplying that man’s need.’

Mr. Opie had spoken rapidly and with enthusiasm, and Dr. Czinner found his knowledge of English failing him. He did not understand the words ‘pad,’ ‘wickets,’ ‘runs;’ he knew only that they were connected to with the English game of cricket; he had become familiar with the words during the last five years and they were associated in his mind with salty windswept turf, the supervision of insubordinate children engaged on a game which he could not master; but the religious significance escaped him. He supposed that the priest was using them metaphorically: ‘responsibility,’ ‘crisis,’ ‘man’s need,’ these phrases he understood, and they gave him the opportunity he required to make his request.”

A few things about this:

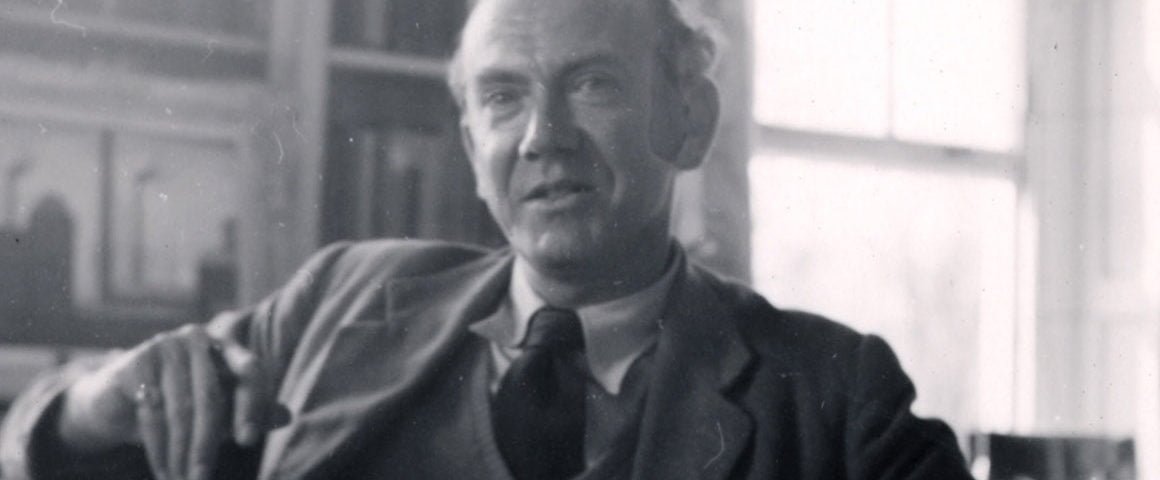

First, Graham Greene had notorious communist sympathies, but was nevertheless a devout Catholic who wrote actively on Church politics and had strong opinions on the mid-twentieth century liturgical reforms.

Catholic and Communist seem oxymoronic. William F. Buckley, for instance, thought Greene was “at war with himself. He had impulses that he sometimes examined with a compulsive sense to dissect them, as though only an autopsy would do to dissect their nature. was a Christian more or less malgré soi. He was a Christian because he couldn’t quite prevent it.”

However, in this passage, far from being a contradiction, the communist and the conservative Christian impulses are perfectly aligned in that they both speak a universal moral language that seeks to transcend the matters of every-day life.

Second, Graham wants us to think about what happens when religious bodies undertake the effort to update and modernize religious texts.

Here, the priest – Mr. Opie – wants to be relevant. He wants to speak the language of his time. But in doing so he is not reaching his culture with anything they don’t already possess. And furthermore, he is limiting his own religious body’s reach by trying to speak the contemporary language of one class and nationality rather than the universal language of love and duty. He is not expanding his church’s reach by talking about cricket, he is in fact limiting it to something accessible by only a select group of bourgeoisie English families. I often think the banalities of praise and worship music are similarly limited to the “struggles” that afflict American suburbanites.

It is not the “common prayer” that the English world or the Latin world previously enjoyed. It is prayer in the language of different classes and groups that is often known only to them.

And Greene seems to be hinting at the question “to what are they praying?”

Themselves.

'Praying to Themselves' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!