Introduction:

Is theological rigorism—insistence on conformity to the Prayer Book, and other traditionally “high church” distinctives—conducive to mission and evangelism? The assumption of many (even many high churchmen themselves) is that in order to do successful evangelism, many of their distinctives have to be downplayed. However, history tells another story. Even here in America, in the bastion of individualism and nonconformity, almost all of the successes of the Anglican/Episcopal tradition can be claimed by high churchmen. Yes, almost all of the lasting foundation-laying successes of the Episcopal Church in America were historically rooted in high church evangelism. The very foundations upon which all of North American Anglicanism stands owes an enormous debt to a particular Old High Church “revival” in Connecticut from the 1720s which saved the Church here in the New World.

The Yale Apostasy

In 1691, a new colonial charter provided Anglicans the right to worship without interference and to vote and have representation in all of the colonies, even in the colonies which had established other confessions like Congregationalism.[1] So while Congregationalism remained the established religion in Massachusetts and Connecticut, the Church of England was now able to operate in these colonies. Still, by the 1720’s there were no permanent Church of England churches in New England. Not until one of the graduating classes of Yale began looking into the theology of ordination. In 1722, the rector of Yale, Timothy Cutler, and seven other ministers, including Samuel Johnson, and James Wetmore were convinced of episcopal succession and of the invalidity of their ordinations as congregationalist ministers. They announced their change of opinions at that year’s commencement causing the beginning of an enduring pamphlet war in New England over the “Great Apostasy” or the “Yale Apostasy” as it came to be known.

All of them were expelled from Yale (including the rector) and shortly thereafter they left for Old England to receive ordination under episcopal Apostolic Succession and returned to New England to plant the first Anglican churches in the region. The surrounding Puritans were very hostile to the new Anglican presence in the colony, and the following years were marked by an ironic role reversal of the dynamics in Britain which caused the original flight of the Puritans wherein the Anglicans were the dissenters being repressed by a hostile Puritan establishment. However, the new Anglican ministers were insistent that the 39 Articles of Religion and the Prayerbook tradition represented the primitive faith, and fired back at their accusers in public newspapers and distributed loads of written material defending the Anglican Way. The Rev. Samuel Johnson opened the first Anglican church in New England, Christ Church in Stratford, Connecticut. But he did not stop there. In addition to wading into the Old Light/New Light debates of his day, local politics, and other theological debates (evening having a back and forth with Jonathon Dickinson, the then President of Princeton) via his frequent writing and publishing, Dr. Johnson also planted 25 churches across the rest of New England by 1752. His successes were despite onerous targeted taxation and penalties that began to be imposed upon Johnson and the Anglicans (which Johnson argued were in violation of the 1691 statute of protection, but continued unabated nonetheless).

Eventually, Johnson even became the first public proponent in America to petition for a New World Anglican bishop. He received harsh criticism for his position, both from Puritans who supposed he intended to uproot the entire establishment and convert the entirety of New England to Anglicanism by force, and from southern Anglicans who enjoyed the freedom of having little to no oversight.

An American Episcopate?

Support for bishops was controversial at least in part because of the explicitly political role of bishops in England, so most Anglican ministers in the middle and south simply didn’t care for it but the New England Old High churchmen were committed to establishing an American episcopate. Episcopalianism was the very reason for their identity. This made them enemies with the majority dissenter establishment, and even John Adams cited the petition for a bishop as one of the major motivations for the Revolution in New England. Still, they were more committed to theological truth—in this case, ecclesiology—than they were to political expediency or creature comforts.

This quickly evolved into a “culture war” with the rest of Dissenter New England. While the majority of New England was not loyal to the Church of England, and the episcopalians were a clear minority, the establishment certainly felt threatened by the rise of the Church of England in New England. This meant that the growing episcopalian movement in the North answered this opposition by appealing to the higher authority of Parliament and England. Quickly this made them a hotbed for “loyalism” and Toryism.

In the north, the loyalist movement was basically synonymous with episcopalianism. Scholars estimate about 27% of Anglican priests in all of the colonies were Patriots, 40% were loyalists, and the remainder were not committed either way. But these averages changed very quickly depending on the colony. Of the 55 Anglican clergy in New England and New York, only three were Patriots.

In Virginia and the South, most of the Clergy actually were Patriots (with the exception of Maryland clergy), loyal to the state government which supported them financially and paid their salaries. New York and New Jersey had only one patriot priest a piece, and the Rev. Samuel Provoost of New York became one of the first bishops of the Episcopal Church, based solely on his Patriotism, since he could be trusted in the new republican order. His Patriotism however correlated with the fact that he was largely a latitudinarian, who, at best, was not as strict as the New England clergy on doctrine, and, at worst, was privately heretical. The Northern Old High Church establishment certainly favored the latter interpretation. He was at least sympathetic to unitarianism and opposed putting the creeds in the Prayer Book. Many of the rigorist theologians of the North suspected him as being a crypto-unitarian and many, like Sainted Seabury, made their vehement disgust with Provoost known.

Northern Old High Church Revival

Despite the distractions of politics, and the campaign for a bishop, this did not slow the Northern Old High Church Revival, which was happening in the lead-up to the Revolutionary War. Connecticut was the most zealous for evangelism and church planting. In 1761 there were 30 Anglican churches in Connecticut but by 1774, 47 were reported.[2] This was the largest growth in sheer numbers (17) of any colony despite the largest number of Anglican churches being concentrated in Maryland and Virginia. Maryland only added 10 in that time, and Virginia added 9.[3] In the years leading up to the Revolutionary War, clergy in every colony reported steadily increasing church attendance in the decade leading up to the Revolutionary War, and the need for more clergy was becoming evident. In the Northeast, we have a number of specific reports, collected by a Dr. Samuel Johnson of Stratford who sent testimony from clergy to the Archbishop of Canterbury asking for new clergy so that packed churches could subdivide into new missions and church plants. A local missionary Edward Bass reported large attentive congregations in his church plant, a church in Marblehead, Massachusetts made up of multiple large families flocking to their Anglican church, and the rector of Trinity Church in New York, reported that the church and the adjoining chapel were both filled to the bursting on Sundays.[4]

Whereas in Virginia (which had the largest number of clergy at 122 in 1776) clergy were often acquired from overseas (according to incomplete internal reporting only 38 of the 122 were recorded as having been born in Virginia), New England reared the vast majority of her own clergy with 65 of their collective 90 clergy being from New England, and five more being from other northern colonies, and a further 60 of these priests were converts from Congregationalism.[5] What’s even more remarkable is that while clergy supported by tax dollars in Maryland and Virginia had hefty salaries, around £250-£300 annually compared to £133 average in South Carolina, £25 to £50 in Georgia, and £100 to £150 in England itself, the clergy in New England relied on support from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts and the charity of their parishioners.[6] Most SPG missionary support packages were about £50 annually. This was meant to cover, not only the rector’s salary, but also to cover the other church expenses like buying Bibles, Prayer Books, repairing buildings, and even building new ones.[7] This led some SPG missionaries to come up with creative fundraising projects like a priest in Philadelphia who raised £3000 with a lottery.[8] Despite poor funding, by 1774, one in every thirteen persons in Connecticut was Anglican.[9] Frederick V. Mills in his book “Bishops by Ballot” explains the great gains of this period as being partly caused by the internal divisions of Congregationalism into the New Light and Old Light factions. “In the eye of this religio-political storm the Church of England adhered to its liturgical form of worship and as a result attracted numbers of persons who wanted to escape the turbulence that had engulfed Congregationalism.”[10]

Fall from Grace

In many ways, the success of the American Revolution proved to result in the nuclear scenario that New England loyalist Anglicans had predicted. Many Anglican churches in the North (associated with loyalism) had their priests run out of town, occasionally had property seized, or were by other more creative means prevented from operating. 80,000 people (about 15% of the population of America at that time) left, most for Canada and the vast majority of them were Anglicans and more specifically products of the Old High Church revival like Charles Inglis, who had been a prominent rector and priest in New York City, but ended up being the first bishop of the Church of England in Canada. This, combined with the clear split with Methodists (which was sparked also in large part by Sainted Seabury’s theological rigorism and class snobbery) left the newly formed Protestant Episcopal Church depleted and incredibly vulnerable.

The Anglican/Episcopalian population in 1790 was reduced to about 10,000, only about .25% of the population. The established church in Virginia before the war had 107 parishes, but after the war only 42 aligned with the Episcopalian movement. In Georgia, only a single parish remained both operational and Anglican, Christ Church in Savannah. In Maryland, half of the Anglican churches were left inoperable from 1790 to 1800. North Carolina had only one priest until, in 1816, he died.

It was obvious to all, that even after bishops were secured, the nascent Episcopal Church was in a state of total crisis, on the edge of oblivion. Bishop Provoost eventually abandoned his post to study botany, and swore that the Episcopal Church was a generation away from dying out.

Bishop William White’s solution was compromise. He first proposed a new Constitution and Prayer Book which conceded huge areas of doctrine to the new ascendant republicanism (replacing the roles played by the government and the king in England, with democratic lay participation) and then attempted to reconcile the Episcopalian differences with the Methodists. Prior to the actual ordination of any bishops, William White supported the Methodist plan to create bishops by-election from the presbyters. The Connecticut clergy were appalled by this plan and sent Samuel Seabury to petition for ordination in Apostolic Succession in Britain. Seabury and his faction, which were disproportionately concerned with theology and details at the first conventions, were eventually appeased.

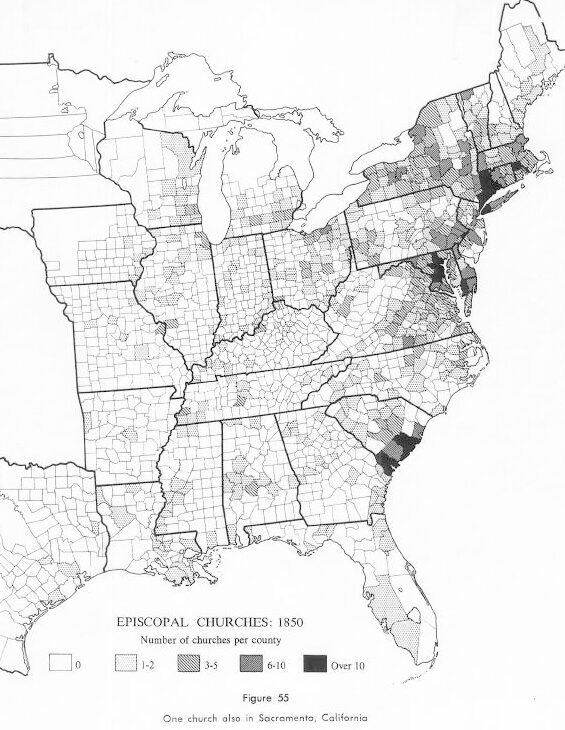

The irony is that while Seabury was ridiculed for hurting the Episcopal Church by his strict orthodoxy and lack of ecumenical fervor, a map of the Episcopal Church in the 1850s (nearly half a century later) demonstrates that the High Church dioceses like Connecticut and Bp. John Henry Hobart’s New York (which from 1800 to 1810 almost doubled in parish count from 26 to 50 despite an increase in the population of only 20% at that time from 60,000 to 72,000 while the rest of the church was dying out), were able to actually establish consistent footholds and widespread, enduring parishes. Compare this to latitudinarian Virginia and Pennsylvania which were much larger in total population than Connecticut, South Carolina, and Rhode Island. Even more shocking when looking at this map of Virginia is realizing that prior to the Revolutionary War, the Church of England was established by law in Virginia, and people had to pay a fine for not attending Anglican churches. It had by far the largest number of clergy and parishes, but the prominent latitudinarian attitude meant that the Anglican legacy quickly diminished after the war.

The Fruit of Latitudinarian Seeds

Compare this especially to Georgia, which was explicitly founded during a period of Latitudinarian ascendancy and which was dominated by “liberal” Anglicans up to the Civil War.[11] In 1735, the board of trustees for the settlement of Georgia began encouraging immigration from Moravians, Jews, Presbyterians, French Huguenots, Swiss Calvinists, and even four Romanists thinking the latitudinarian establishment could thereby be proved in the assimilation of those to the more vague Anglicanism present there. This did not work, and quickly thereafter other ministers were sought to shepherd the dissenters.[12] John Wesley visited that same year and chastised the local Georgians for not following the liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer exactly enough, and even felt he had to rebaptize many of their babies. Frustrated with their prevarications he eventually exclaimed to them: “my poor friends, you are the scum of the earth.”[13] He began a Sunday School there while he was rector at Christ Church in Savannah, for the explicit purpose of instructing the locals in the Anglican catechism, even teaching himself Spanish so that he could evangelize the local Jews.[14] His ministry was actually fairly successful. Wesley later recalled a time that a local dance was scheduled at the same time as morning prayer and rejoiced that “the Church was full while the ball-room was so empty that the entertainment could not go forward.”[15] Wesley then had a falling out with some of the locals and was ultimately replaced by another early Methodist leader, George Whitefield, at his old parish. In response to Whitefield’s public and loud and extempore preaching, the Trustees appointed a more subdued Rev. William Norris. This set in stone the spectrum of Georgian Anglicanism between Latitudinarianism and Evangelical Methodism. One dependent on unobtrusive ministers, and the other, eventually on revivalism, with large tent gatherings becoming common there during the Great Awakening. Peculiarly absent as an influence in Georgia, was the Old High Church. Even though individual preachers like Wesley, Whitefield, and their successors were able to draw temporary large crowds, by 1850, the seed had long been scattered, the roots torn out, and the branch of the Anglican Church there withered.

So what happened in South Carolina? It seems like the only healthy state in the Deep South. Well in the original 1662 charter for the colony of South Carolina, adherence and agreement to “be subject and obedient to all other the Laws, Ordinances and Constitutions of the said Province, in all matters whatsoever, as well Ecclesiastical as Civil, and do not in anywise disturb the Peace and Safety thereof, or scandalize or reproach the said Liturgy, Forms and Ceremonies, or any thing relating thereunto…”.[16] The proprietors drafted a Constitution for Carolina, much celebrated by John Locke, that included articles such as “Ninety-five. No man shall be permitted to be a freeman of Carolina, or to have any estate or habitation within it, that doth not acknowledge a God, and that God is publicly and solemnly to be worshipped.” and “Ninety-six. As the country comes to be sufficiently planted and distributed into fit divisions, it shall belong to the parliament to take care for the building of churches, and the public maintenance of divines, to be employed in the exercise of religion, according to the Church of England; which being the only true and orthodox and the national religion of all the King’s dominions, is so also of Carolina; and, therefore, it alone shall be allowed to receive public maintenance, by grant of parliament.”[17] As well as having an article which explicitly took away the civil rights of professed atheists (Article 101), South Carolina (which was called in the constitution just Carolina) was established as a model Tory colony by the then ascendant Tory Anglicans during the reign of Charles II, headed by Lord Clarendon of the infamous Clarendon Code.[18] All of the prominent South Carolina families; the Rutledges, the Pinckneys, and Laurens, were churchmen, and they all supported the church in South Carolina and Charleston entirely from their own coffers. The Rev. Charles Woodmason, rector of St. Mark’s in the South Carolina backcountry reported 2,000 baptisms, 100 marriages and 500 “discourses” in 1771 alone.[19] Woodmas was likely a more “Methodist” leaning Anglican at the time, but whereas the spectrum in Virginia ran between Methodists and Latitudinarians, the Methodists in South Carolina were complimented by an upper-crust high church Anglican establishment, zealous for the Prayer Book, many of whom were Patriots, and thus did not leave or abandon their flocks in light of the Revolution.

The High Church Missionary Bishops

The resilience of the Old High Church strain of Anglicans meant that the Northern Old High Church movement, which began in the 1720’s, was sustained by Bishop Seabury in the Revolutionary and post-revolutionary period, continued to produce many bishops and clergy essential in mission as expansion west began in earnest in the 19th century. Among the High Church missionary bishops, Philander Chase ranked high, along with Jackson Kemper, the founder of Nashotah House.

The great Bishop Philander Chase’s father, who was a devout Congregationalist, migrated to New England where he thought his children would be safely raised in the heart of Congregationalism (and indeed three of his sons became Congregationalist ministers). Meanwhile, entering into the committed domain of Episcopalians at Dartmouth, who were confident in their tradition’s distinctives, and who had a deep love for the Book of Common Prayer, the young Philander Chase was converted to Episcopalianism.

This robust defense of Anglican distinctives by a couple of college students made one convert, who eventually became a bishop who would himself become one of the key “missionary bishops” of the 19th century who were appointed to the sparsely populated western dioceses, where, after the tradition of Sainted Seabury, he was an avid church planter. Indeed, Philander Chase’s first posting (after he helped plant a church in his hometown as a lay reader shortly after his graduation in 1795) as a rector was in Poughkeepsie at a church planted thirty years earlier by Seabury himself! He left that posting to plant the first Episcopal church in Louisiana, the eventual Christ Church Cathedral. After briefly returning to New England, he planted another Christ Church Cathedral in Cincinnati. From here he organized the nascent church in Ohio, almost entirely on his lonesome. Organizing the first unfunded diocesan convention (where the five other clergy of Ohio elected him as their unfunded bishop).[20] He returned to Philadelphia to be consecrated by White, Hobart, and two other bishops. Without pageantry or further ado, he returned immediately on horseback to Ohio to renew his evangelical efforts. Between June 1820 and June 1821, he preached 200 times, baptized 50 people, and confirmed another 175 while traveling 1,279 miles on horseback.[21]

His love of the prayerbook ran right through all of his preaching. Early in his travels, stopping in a public space where a crowd was gathered he suddenly enjoined them all to worship God saying:

Neighbors, I hold in one hand a Bible, in the other a Prayer-Book. The one teaches us how to live, the other how to pray. I know you are familiar with the one, I doubt if you are with the other. I have brought some dozens of copies with me. With the aid of these, my good brethren, I will try to lead you in the service. If any of you, through depravity of the natural heart, are averse to being ‘taught how to pray,’ you need the teaching all the more on that very account. Without confession there is, as you know, no remission of sins. We will therefore confess our sins to Almighty God, all in the same voice. You will observe that no man can say ‘Our Father’ until he has confessed his faults; we will now say ‘Our Father who art in heaven.’ The proper attitude when we pray is upon our knees, as did Solomon, Daniel, Stephen, and Paul. After their example, I enjoin upon you all to fall upon your knees.[22]

And many happily joined him, “the response from the great congregation being as the voice of many waters”.[23]

Conclusions

And so what was planted by a few theology nerds at Yale in 1720, established the basis, and continued to inspire and raise up leaders, for the nascent church in America. Theological rigorism, rather than being stuffy and dangerous to the health of the church, created a lasting foundation, especially in comparison to those places where latitudinarianism was embraced.

What can be observed? Commitment to Anglican distinctives, like our ecclesiology, the Prayer Book, the Articles, and the Creeds, often creates fierce opposition from those inside and outside the Church. The temptation to compromise with some faction or another, be they secular or sectarian, is palpable. While these compromises might protect us from criticism in the short run, they do not lay a stable and enduring foundation for the following generations. Without the Prayer Book, and our Anglican distinctives, what are we even bringing people to? After all, the Prayer Book and the Articles are not random adiaphora, but the very distinctives, which are the doctrinal reason for our existence. If we don’t think that they are true, to the exclusion of contrary convictions, the “church” becomes a club for antiquarians and bad actors attracted to the institution for ulterior motives. If they are not true, to the exclusion of contrary convictions, we ought not to exist and are in vile schism from other church bodies which hold perfectly acceptable positions and practices. Even if we do not see the truth of that, many clergy and laity do, and when they no longer gain from their affiliation with the Anglican church, they will leave for safer ground.

Because the Prayer Book is the catholic liturgy of the church universal, reformed and purified by the Word of God, it is the greatest tool for evangelism, after the Holy Scriptures themselves. I think Bishop Philander Chase couldn’t have said it better: “Neighbors, I hold in one hand a Bible, in the other a Prayer-Book. The one teaches us how to live, the other how to pray.”

Notes

- “Bishops by Ballot: An Eighteenth Century Ecclesiastical Revolution” by Frederick V. Mills, Sr., pg. 16 ↑

- Ibid. pg. 12 ↑

- Ibid. pg. 13 ↑

- Ibid. pg. 14 ↑

- Ibid. pg. 7 ↑

- Ibid. pg. 10 ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. pg. 36 ↑

- Ibid. pg. 39 ↑

- “The Episcopal Church in Georgia, 1733-1957” by Malone, Henry Thompson, pg. 6 ↑

- Ibid. pg. 12 ↑

- Ibid. pg. 13 ↑

- Ibid. pg. 14 ↑

- Ibid. pg. 13 ↑

- “An historical account of the Protestant Episcopal Church in South-Carolina, from the first settlement of the province, to the war of the revolution; with notices of the present state of the church in each parish: and some account of the early civil history of Carolina, never before published. To which are added; the laws relating to religious worship; the journals and rules of the convention of South-Carolina; the constitution and canons of the Protestant Episcopal church, and the course of ecclesiastical studies” by Dalcho, Frederick, (1770-1836) p. 3 ↑

- Ibid. p. 4 ↑

- Ibid. p. 6 ↑

- Mills, p. 15 ↑

- “The American Episcopal Church” by. S.D. McConnell, p. 303 ↑

- John N. Norton, Life of Bishop Chase p. 44 ↑

- McConnell. p. 304 ↑

- Ibid. ↑