Dear Reader,

Beloved in Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, it seems fitting to begin my poor discourse (in which nothing new can or will be said) by quoting the Anglican Doctor, the Reverend Richard Hooker:

Think not that ye read the words of one who bendeth himself as an adversary against the truth which ye have already embraced; but the words of one who desireth even to embrace together with you the selfsame truth, if it be the truth…[1]

The zeal that has animated our respective parties over the last 450 years or so, producing the perennial headbutting that has so tragically come to characterize our tradition, is ironically maintained by a shared aim: “the setting forth of Gods honour and glory.” Contrary approaches to this single, pious aim have occasioned nothing less than the disastrous rupture of one nation and the founding of another. I would invite us, however, to learn from the charity of the Reverend Canon J. I. Packer of blessed memory, who wrote of the High Church party, “…they were men thoroughly sincere in seeking to please God, serve God, and proclaim what they took to be the truth of God.”[2] Likewise, I cannot but recognize across the aisle sincere lovers of God, utterly earnest in their desire for the purity of His worship. And so I recognize family.

Yet! Even families must from time to time voice discordant perspectives[3] (Thanksgiving is just around the corner, after all), and so—at the risk of occupying myself with things too great and too marvelous for me—I would like to offer my own humble thoughts on the place of images in the Church. By the mercy of God, may my words serve to magnify the only wise God who has given the light of the knowledge of His glory in the face of Jesus Christ.

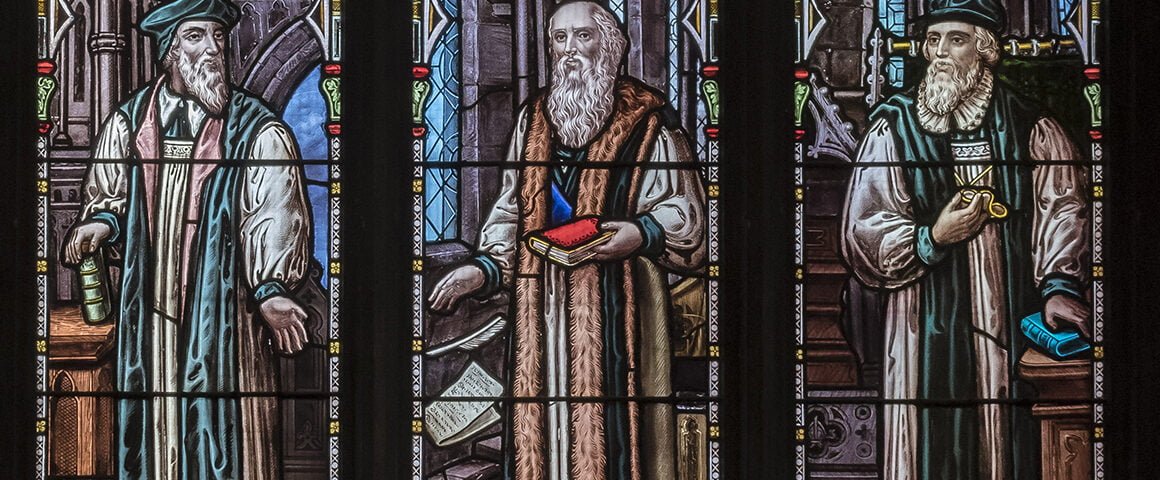

In the Venerable Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, we read of the auspicious meeting in the late sixth century between a (briefly reluctant) monk named Augustine and King Æthelberht of Kent. Commissioned by Pope St. Gregory the Great, Augustine and around forty other missionaries had arrived on the strange shores of Britain “to preach the word of God to the English race.”[4] One of Æthelberht’s terms for this meeting was that he be allowed to receive his guests in the open air, lest he fall victim to a magical spell that could be pronounced in a closed space. Yet, as St. Bede writes, “they came endowed with divine not devilish power and bearing as their standard a silver cross and the image of our Lord and Savior painted on a panel.”[5] Following litanies and prayers for themselves and their hearers, the monks “preached the word of life” to the king and his court.[6] Though not quite ready to convert, Æthelberht granted them every advantage, including the gift of a dwelling in a city called Canterbury. St Augustine and his brothers processed into their new home “in accordance with their custom carrying the holy cross and the image of our great King and Lord, Jesus Christ.”[7]

Before we consider why the first Archbishop of Canterbury would be persuaded to commit the impropriety of parading around an image of our Lord in solemn procession (and before a pagan, no less), let us consider how the Church warns against the improper use of images. For we’ve lately had the benefit of a welcome reminder regarding the danger of images in the Church. On the Feast of St. Luke the Evangelist and Companion of St. Paul (ironically, supposed by some to be the Church’s first iconographer), an article by my beloved brother, Mr. Jared Willett, was published in which, by way of a helpful survey of certain English Reformation documents, he raises the question of the “appropriateness of images in worship.”

His encouragement to caution is well taken. Indeed, discernment has often been prescribed throughout church history when it comes to images, even among the most iconophilic of Christ’s followers. At the Second Council of Nicaea in AD 787, a careful (and oft-repeated) distinction is made between the “honourable reverence [προσκύνησιν]” of images as opposed to “that true worship [λατρείαν] of faith which pertains alone to the divine nature.”[8] This distinction is repeated in the Catechism of the Catholic Church,[9] and even St. Philaret of Moscow in his Longer Catechism does not pass over in silence the possibility of an ungodly use of images:

521. Is the use of holy icons agreeable to the Second Commandment?

It would then, and then only, be otherwise, if any one were to make gods of them; but it is not in the least contrary to this commandment to honor icons as sacred representations, and to use them for the religious remembrance of God’s works and of his saints; for when thus used icons are books, written with the forms of persons and things instead of letters.[10]

Despite these cautions, it is clear that the faithful lapsed into faithlessness regarding images and the devotion to the saints more generally in the centuries leading up to and including the sixteenth century. Prof. Eamon Duffy of Cambridge writes,

[The client] ‘adopted’ specific saints in the hope that he or she would be adopted and protected in turn…this relationship was essentially feudal, and the saint was bound by a sense of noblesse oblige towards those who paid him honour and financial tribute in the shape of tithe and wax…[11]

One example of this idolatrous excess can be seen in 1520, where the parish priest of the village Morebath commissioned a new statue of St. Sidwell and placed it on the “Jesus altar” (where masses were said in devotion to the Holy Name of Jesus). Within a decade, “the altar on which [the statue] stood was no longer referred to as Jesus’ altar but St Sidwell’s altar…”[12]

No doubt some medievalists would interject here and attempt to explain the interconnected intricacies of the mass, the intercessory role of the saints, and the cultic expressions of folk piety, but even Rome felt compelled to address the matter in the twenty-fifth session of the Council of Trent (December 1563):

Furthermore, in the invocation of the saints, the veneration of relics, and the sacred use of images, all superstition shall be removed, all filthy quest for gain eliminated, and all lasciviousness avoided, so that images shall not be painted and adorned with a seductive charm, or the celebration of boisterous festivities and drunkenness, as if the festivals in honor of the saints are to be celebrated with revelry and with no sense of decency.[13]

As the Church in Rome addressed the matter after her fashion (incompletely, as we Anglicans maintain), so the Church in England attended to the pruning of devotional errors. In his essay, Mr. Willett tracks the development of this pruning in regard to images by laying out the Articles of Religion in their various iterations, the Royal Injunctions, and the Homilies. Willett discusses this development in terms of optimism and pessimism over the place of images in the Church, eventually arriving at the summit of “An Homily Against Peril of Idolatry and Superfluous Decking of Churches” (and briefly the homily “Of Good Works”) as the most pessimistic and therefore (shifting his essay somewhat from its descriptive tenor to a prescriptive conclusion) indicating it to be the most commendable. But one (perhaps unintended) consequence of this survey is the light it shines on a generally positive (or at least ambivalent) view of images among the religious leadership of England throughout the sixteenth century, including from the mouth of the Most Rev’d Thomas Cranmer himself in the Thirteen Articles of 1538![14]

Even a close reading of the homily, “Against peril of Idolatry,” itself does not necessitate the utter prohibition that the Puritan-leaning among us would recommend. Twice in the homily, as the Rev. Dr. Gerald Bray notes, Queen Elizabeth I interjects to ameliorate the biting rhetoric of her homilist: once near the end of the first section to replace “neither that any true Christian ought to have any ado with filthy and dead images” with the starkly moderating “though [images] be of themselves things indifferent.” [15] And again at the beginning of the third section to add:

(I mean always thus herein, in that we be stirred and provoked by them to worship them, and not as though they were simply forbidden by the New Testament without such occasion and danger.)[16]

So Her Royal Highness (and Defender of the Faith[17]) felt the need to rein in the homily at certain points, in a manner that suggests allowances for images in certain contexts (though never for worship). These amendments provide consonance with prior statements on images and a somewhat more organic trajectory than the manifesto of iconoclasm this homily presents otherwise.

Yet even when the Homilist is allowed to speak freely, he occasionally reveals a more nuanced position, as can be seen in his quotation of St. Ambrose regarding St. Helena and comments following:

Saint Ambrose…saith: ‘Helena found the cross and title on it; she worshipped the king and not the wood surely…but she worshipped him that hanged on the cross…’ See both the godly empress’ fact and Saint Ambrose’s judgment at once. They thought it had been an heathenish error and vanity of the wicked to have worshipped the cross itself…[18]

Here, briefly, the Homilist acknowledges the possibility of a semiotic relationship between an image (the cross) and that which is being imaged (the One who hung on the cross), a connection also described by St Basil the Great:

Just like the sun, [the Holy Spirit] will use the eye that has been cleansed to show you in himself the image of the invisible, and in the blessed vision of the image you will see the unspeakable beauty of the archetype.[19]

Our Lord Himself chastises the scribes and Pharisees for collapsing this relationship between the images and the imaged:

16 “Woe to you, blind guides, who say, ‘If anyone swears by the temple, it is nothing, but if anyone swears by the gold of the temple, he is bound by his oath.’ 17 You blind fools! For which is greater, the gold or the temple that has made the gold sacred? 18 And you say, ‘If anyone swears by the altar, it is nothing, but if anyone swears by the gift that is on the altar, he is bound by his oath.’ 19 You blind men! For which is greater, the gift or the altar that makes the gift sacred? 20 So whoever swears by the altar swears by it and by everything on it. 21 And whoever swears by the temple swears by it and by him who dwells in it. 22 And whoever swears by heaven swears by the throne of God and by him who sits upon it.” (Matthew 23:16-21)

Indeed, it is when the divine is terminally localized to the “gold or silver or stone” (Acts 17:29) physically before the votary that idolatry occurs, as when Aaron gave the Israelites their golden calf before which they exclaimed, “These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt!” (Exodus 32:8). Dr. Jaroslav Pelikan of blessed memory provides a helpful framework for distinguishing between idols and images/icons in the 1983 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, published as The Vindication of Tradition. Pelikan maintains that an idol “purports to be the embodiment of that which it represents, but it directs us to itself rather than beyond itself; idolatry, therefore, is the failure to pay attention to the transcendent reality beyond the representation,” whereas an icon “is what it represents; nevertheless, it bids us look at it, but through it and beyond it, to that living reality of which it is an embodiment.”[20]

Now, this is all well and good, but as Mr. Willett noted, “the disagreement comes not from whether or not you can make an image of God after the incarnation but whether you should.” As good children of the Reformation, let us turn to Scripture to find our doctrine.

In Exodus 25, after bringing the Israelites out of the “iron furnace” (Deut 4:20) of Egypt, after giving them bread from heaven and water from the rock, after making a covenant and giving Torah, the Lord gives a Pattern, “Exactly as I show you concerning the pattern of the tabernacle, and of all its furniture, so you shall make it” (Ex 25:9). And with the second commandment firmly in place, untouched and unrepealed, the Lord gives another command, regarding the tabernacle where He will dwell in the midst of His people, “And you shall make two cherubim of gold; of hammered work shall you make them, on the two ends of the mercy seat…The cherubim shall spread out their wings above, overshadowing the mercy seat with their wings, their faces one to another…” (Ex 25:18, 20).

Article XX of the Articles of Religion, which remain authoritative today for Anglican churches, binds me from “expound[ing] one place of Scripture, that it be repugnant to another,” and so I must conclude that God’s command to bring golden images into the tabernacle (which is reckoned by the homily “Of the right use of the Church” to exist today as the church)[21] does not violate the earlier command not to make “a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth” (Ex 20:4). Furthermore, we know from elsewhere in Scripture that our Lord chose cherubim because these images signify the heavenly reality (as the prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel bore witness[22]) as “copies of the heavenly things” (Heb 9:23). Is it so strange then that, in the Church where the Law and Prophets have not been abolished but fulfilled (Matt 5:17), where the veil of Moses has been lifted, and we all, with unveiled face, behold the glory of the Lord (2 Cor 3:12-18), where once we saw in a mirror dimly but now face to face (1 Cor 13:12), the new tabernacle should echo the new heavenly reality, where the Son of Man is seated at the right hand of Power (Matt 26:64), attended by ten thousands of His holy ones (Jude 1:14)?

It cannot be denied that “Against peril of Idolatry” uses strong language to combat a real problem. The pruning was necessary for the health of the vine. But we must keep both the fasts and the feasts of the Church. The homily was crafted to accomplish what all good homilies try to do: persuade their audience. And preachers understand that sometimes one leans into stronger language when the people have grown numb to the danger. Our Lord was no stranger to hyperbole: “if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away” (Matt 5:30). Show me where your right hand is, and I’ll show you if you have hermeneutical space for hyperbole.

Rather, if there was ever a time for the right use of holy images, as defended at the Seventh Ecumenical Council, it’s now. Men, women, and children are drowning in an ever-rising ocean of unholy images. Some of the vilest sorts of moving images ever known to mankind can be summoned up on a whim by the unassuming screens we keep in our pockets, offices, and living rooms. In fact, I would submit that the difference between spending ten minutes in stillness before an image of the Lord Jesus Christ and the savage flood of uninterrupted stimuli we usually subject ourselves to is by degree a greater difference than that between an image and its absence. This is the pastoral situation, and the catechesis of holy images is needed to heal the visual plague we inhabit. If our children can be trusted with pledging allegiance to a flag (caps off, hands over hearts) or bowing to a monarch, certainly we can hazard the right use of holy images.

And perhaps unlike any time before, we are being ushered into the Great Disincarnation, the Inglorious Disintegration, that the gospel militates against. As Mark Zuckerberg invites us into the Metaverse, where we can “play virtual games, attend virtual concerts, go shopping for virtual goods, collect virtual art, hang out with each others’ virtual avatars and attend virtual work meetings,”[23] we need to proclaim the scandal of the Incarnation that holy images bear witness to, where Christ meets us in the sweat, pain, toil, and glory of these enfleshed lives. “I do not worship matter,” writes St John of Damascus, “I worship the Creator of matter who became matter for my sake, who willed to take His abode in matter; who worked out my salvation through matter. Never will I cease honoring the matter which wrought my salvation!”[24] This has implications for the religious as well as the secular sphere: in what sense are we worshippers if our bodies never learn the posture of worship? Are our bodies not part of us? C. S. Lewis writes in Letters to Malcolm,

When one prays in strange places and at strange times one can’t kneel, to be sure. I won’t say this doesn’t matter. The body ought to pray as well as the soul. Body and soul are both the better for it. Bless the body…but for our body one whole realm of God’s glory – all that we receive through the senses – would go unpraised. For the beasts can’t appreciate it and the angels are, I suppose, pure intelligences. They understand colours and tastes better than our greatest scientists; but have they retinas or palates?[25]

Likewise, St. John Damascene notes, “The eloquent Gregory says that the mind which is determined to ignore corporeal things will find itself weakened and frustrated.”[26] Fellow Anglicans, as the psalmist could exclaim, “Let us go to his dwelling place; let us worship at his footstool[27]” (Psalm 132:7), so reverence His altar; as St. Helena adored the Lamb of God by venerating the cross on which He was slain, so bow before the cross at procession; as every knee shall bow at the name of Jesus (Phil 2:10), so bend your neck when you hear it said in church. The practice will make you ready at His glorious appearing.

Let no one hear me calling for the opening of the indiscriminate floodgates with regard to religious images. There is plenty of bad religious art,[28] and there are venerable schools of iconography that have honed the craft over centuries of practice. As with anything, there are plenty of mistakes that can be made and pitfalls to stumble into. As St. Peter admonished, “Be sober-minded; be watchful. Your adversary the devil prowls around like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour” (1 Peter 5:8).

The Reformers gave an example to follow in speaking boldly when error had crept into the Church. There is a time to demolish the bronze serpent when it becomes an idol, but there is also a time to hold it aloft, perhaps even when storming pagan shores with the gospel. To raise high the holy images of Christ that by them the people may see and worship the Incarnate Son of Man who was lifted up and draws all people to Himself, to whom be glory, honor, and worship, with the Father and the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto the endless ages of ages. Amen.

Notes:

- Hooker, Richard. Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, vol.1. J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd, 1958, p. 79. ↑

- Packer, J. I. The Heritage of Anglican Theology. Crossway, 2021, p. 253. ↑

- Gal 2:11 ↑

- The Venerable Bede. The Ecclesiastical History of the English People. ed. Judith McClure and Roger Collins. Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 37 (I.23). ↑

- Ibid., pp. 39-40 (I.25). ↑

- Ibid., p. 40 (I.25) ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Creeds of the Churches. 3rd ed. ed. John H. Leith. Westminster John Knox Press, 1982, p. 56. ↑

- , Catechism of the Catholic Church. Doubleday, 1995, p. 573. See questions 2131-2132. ↑

- St Philaret of Moscow. The Longer Catechism of the Eastern Orthodox Church Also known as The Catechism of St. Philaret (Drozdov) of Moscow, trans R.W. Blackmore, ed. Philip Schaff from The Creeds of Christendom, vol. 2. St. Theophan the Recluse Press, 2020, p.204. Emphasis mine. St Philaret then cites St Gregory the Great for support on this point, providing a notable connection to citations of the Theologian in the Ten Articles, the Thirteen Articles, and the Second Henrician Injunctions of 1538, as noted by Mr. Willett. ↑

- Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England c.1400-c.1580. 2nd ed. Yale University Press, 2005, pp. 161-162. ↑

- Ibid., p. 168. Emphasis mine. ↑

- Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent, trans. Rev. H.J. Schroeder, O.P. B. Herder Book Co., 1960, p. 216. Interestingly, this canon makes the same connection between abuse of images and greed/covetousness that is made in the homily, “Against peril of Idolatry.” ↑

- To those who would object at this point that Cranmer was being theologically hampered by political considerations, not least of which was the imposing figure of Henry VIII, I would respond that there are a number of political forces to choose from as manipulating factors on the other side of Edward VI as well. If Henry VIII gave us the moderate Cranmer, perhaps Mary I, Pope Pius V’s Regnans in Excelsis, and endless Jesuit tomfoolery gave us the Puritans. Whether for good or ill, England’s church and state were placed in hypostatic union, and it’s nigh impossible to explain the one without the other. ↑

- The Books of Homilies: A Critical Edition. ed. Gerald Bray. James Clarke & Co, 2015, pp. 227. ↑

- Ibid., p. 249. Emphasis mine. ↑

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. The Reformation. Penguin Books, 2005, p. 135. A title certainly made awkward by her excommunication in 1570. ↑

- The Books of Homilies, p. 233. Emphasis mine. ↑

- St Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit, trans. Stephen Hildebrand. St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2011, p. 38. ↑

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Vindication of Tradition. Yale University Press, 1984, p. 55. Coincidentally, this distinction between idol and icon is also how Pelikan masterfully argues for acceptable and unacceptable use of tradition, summarized in his classic formulation, “Tradition is the living faith of the dead, traditionalism is the dead faith of the living.” ↑

- “And the same church or temple is by the Scriptures both of the Old Testament and the New, called the house and temple of the Lord, for the peculiar service there done to his majesty by his people, and for the efficacious presence of his heavenly grace…Sometime it is named the tabernacle of the Lord and sometime the sanctuary, that is to say, the holy house or place, of the Lord.” The Books of Homilies, p. 207. ↑

- Isaiah 6:1-6; Ezekiel 10 ↑

- Roose, Kevin. “The Metaverse Is Mark Zuckerberg’s Escape Hatch.” The New York Times, October 29, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/29/technology/meta-facebook-zuckerberg.html ↑

- St John of Damascus. On the Divine Images: Three Apologies Against Those Who Attack the Divine Images. trans. David Anderson. St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000, p. 23. ↑

- Lewis, C. S. Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer. Harcourt Brace & Company, 1992, pp. 17-18. ↑

- On the Divine Images, p. 20. ↑

- cf. 1 Chronicles 28:2; The mercy seat is referred to as “the footstool of our God.” ↑

- cf. C.S. Lewis, “How the Few and the Many Use Pictures and Music,” in An Experiment in Criticism (Cambridge, 1961), pp. 17-18, “The Teddy-bear exists in order that the child may endow it with imaginary life and personality and enter into a quasi-social relationship with it. That is what ‘playing with it’ means. The better this activity succeeds the less the actual appearance of the object will matter. Too close or prolonged attention to its changeless and expressionless face impedes the play. A crucifix exists in order to direct the worshipper’s thought and affections to the Passion. It had better not have any excellencies, subtleties, or originalities which will fix attention upon itself. Hence devout people may, for this purpose, prefer the crudest and emptiest icon. The emptier, the more permeable; and they want, as it were, to pass through the material image and go beyond.” Recorded in a footnote of Lewis’ “Christianity and Literature,” Christian Reflections, ed. Walter Hooper, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994, p. 2. ↑

'In Defense of Images' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!