the theology and practice of images in the Jacobean and Caroline Church of England

“And that Images are things indifferent of themselves, is granted in the Homilies which are against the very Peril of Idolatry.”[1]

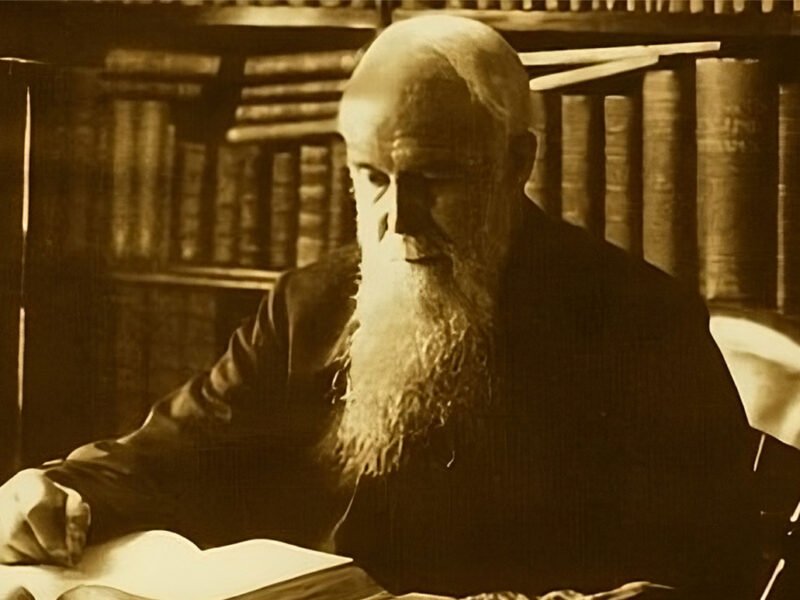

The words are those of Archbishop Laud at his trial, when confronted with charges of ‘Popish idolatry’. Such charges were based on Laud’s chapel having imagery on its reredos (“a Picture of a History at the back of the Altar”) and his possessing three sacred paintings, of the Fathers of the Western Church (Ambrose, Jerome, Augustine and Gregory), of Our Lord as the Good Shepherd, and our Our Lord at His Passion.

Laud’s invocation of the Homilies is significant not least because it might initially be thought that the aggressive and robust nature of the Homily on Peril of Idolatry would make it a rather unlikely source for aid in the circumstances facing the Archbishop. As was excellently pointed out, however, in a recent North American Anglican article by Fr. Daniel Logan, Elizabeth I herself had taken care to moderate the claims of the Homily as the Rev. Dr. Gerald Bray notes:

Twice in the homily, Queen Elizabeth I interjects to ameliorate the biting rhetoric of her homilist: once near the end of the first section to replace ‘neither that any true Christian ought to have any ado with filthy and dead images’ with the starkly moderating ‘though [images] be of themselves things indifferent.’ And again at the beginning of the third section to add:

(I mean always thus herein, in that we be stirred and provoked by them to worship them, and not as though they were simply forbidden by the New Testament without such occasion and danger).[2]

He goes on to note that the Supreme Governor of the reformed ecclesia Anglicana “felt the need to rein in the homily at certain points, in a manner that suggests allowances for images in certain contexts (though never for worship).” This itself is suggestive of space within the reformed ecclesia Anglicana for imagery, echoing Laud’s wider defense of the ceremonial, music, vestments, and imagery of his chapel:

these things have been in use ever since the Reformation … it was in my Chappel, as it was at White-Hall; no difference. And it is not to be thought, that Queen Elizabeth and King James would have endured them all their Time in their own Chappel, had they been introductions for Popery.[3]

It is the case that a consistent defense of the modest use of imagery can be found in the Elizabethan and Jacobean Church. Lancelot Andrewes rejected Roman accusations of iconoclasm, declaring, “To have a story painted, for memory’s sake, we hold it not unlawful, but that it might well enough be done, if the Church found it not inconvenient for her Children.”[4] John Cosin stated likewise the second Commandment condemned “They that make any other images or the likeness of any thing whatsoever, (be it of Christ, and His cross, or be it of His blessed Angels,) with an intent to fall down and worship them” (emphasis added).[5] Cosin also noted that “the Catholic Faith and Religion in the Church of England” allowed for “the historical and moderate use of painted and true stories, either for memory or ornament, where there is no danger to have them abused or worshipped with religious honour.”[6]

For Jeremy Taylor, “the having or making of images though it be forbidden to the Jews in the second commandment, yet it is not unlawful to Christians”, and so “it is neither impious nor unreasonable of itself to have or to make the picture or image of Christ’s humanity.”[7] Richard Montagu’s account suggests that this teaching on the modest use of imagery reflected common practice:

Augustine … witnesseth, that in his time Christ was to be seen painted in many places, betwixt Saint Peter and Saint Paul. So is he in many Churches with us, betwixt the blessed Virgin and Saint John Evangelist … So let them be every where, if you please. Not the making of Images is misliked: not the having of Images is condemned; but the prophaning of them to unlawful uses, in worshipping and adoring them …

The pictures of Christ, the blessed Virgin, and Saints may be made, had in houses, set up in Churches: the Protestants use them: they despise them not. Respect and honour may be given unto them: the Protestants do it: and use them for helps of piety, in rememoration, and more effectual representing of the Prototype.[8]

This is reinforced by the fact that the defence of imagery was not the preserve of avant garde and Laudian opinion. Most obviously, this was seen in the words of another Supreme Governor, James VI/I:

I am no Iconomachus, I quarrel not the making of Images, either for public decoration, or for men’s private uses: But that they should be worshipped, be prayed to, or any holiness attributed unto them, was never known of the Ancients: and the Scriptures are so directly, vehemently and punctually against it.[9]

Mindful that James’ care for consensus and peace in the Church of England was often (unfairly and for polemical purposes) contrasted with the approach of his son, Charles I, this clear rejection of iconoclasm and acceptance of images has considerable significance. We might also note that it is possible to detect here an echo of Luther: “I have nothing in common with the iconoclasts.” John Donne, the epitome of Jacobean Conformity, echoed the words of James in a sermon which, while condemning “Vae Idololatris,” also condemned iconoclasm:

But Vae Iconoclastis too, woe to such peremptory abhorrers of Pictures, and to such uncharitable condemners of all those who would admit any use of them, as had rather throw down a Church, then let a Picture stand.[10]

Donne insists that the Elizabethan Injunctions were not iconoclastic – not a requirement that all images be removed from churches – but a response to the abuse of particular images:

And though the injunctions of our church, declare the sense of those times, concerning images, yet they are wisely and godly conceived; for the second is, ‘that they shall not extol images’, (which is not, that they shall not set them up) but, (as it followeth) “they shall declare the abuse thereof.” And when in the twenty-third injunction, it is said, that “they shall utterly extinct, and destroy,” (amongst other things) “pictures,” yet it is limited to such “things, and such pictures, as are monuments of feigned miracles.”[11]

He also, interestingly, points to wider Protestant practice regarding images, referring to Lutheran custom: “For a reverent adorning of the place, they may be retained here, as they are in the greatest part of the Reformed Church, and in all that, that is properly Protestant.”

Jacobean Conformity, therefore, not only shared with Laudian opinion an acceptance of the use of images, it also shared the same apologia for imagery. Donne’s interpretation of the Elizabethan Injunctions was also that offered by the Laudian Peter Heylyn in his history of the English Reformation, Ecclesia Restaurata:

the commissioners removed all carved images out of the Church which had been formerly abused to superstition, defacing also all such pictures, paintings, and other monuments as served for the setting forth of feigned miracles.[12]

Heylyn also emphasized that any incidences of wider iconoclasm were contrary to the wishes of Elizabeth and the intention of her Injunctions:

And as it is many times supposed that a thing is never well done if not over done, so happened it in this case also; zeal against superstition had prevailed so far with some ignorant men, that in some places the copes, vestments, altar-cloths, books, banners, sepulchres, and rood-lofts, were burned altogether … some, perverting rather than mistaking her intention in it, guided by covetousness, or overruled by some new fangle in religion, under colour of conforming to this command, defaced all such images of Christ and his Apostles, all paintings which presented any history of the holy Bible, as they found in any windows of their churches or chapels.[13]

This coherence of Jacobean Conformity and Laudian sensibilities suggests that Charles Prior is correct in stating that aspects of Laudianism were “deeply entrenched in Jacobean religious culture.”[14] The perhaps surprising figure of Bishop Joseph Hall can be pointed to in support of this judgment. Hall was robustly anti-Laudian, a doctrinal Calvinist, and one of the English representatives at Dort. In the account he provides, however, of the iconoclasm of the 1640s, we see both an acceptance of images and a rejection of the theological principles of the iconoclasts. Referring to the vandalism inflicted by the iconoclasts on his private chapel, Hall states:

Another while the Sheriff Toftes, and Alderman Linsey, attended with many Zealous Followers, came in to my Chappel to look for Superstitious Pictures, and Reliques of Idolatry, and send for me, to let me know they found those Windows full of Images, which were very offensive, and must be demolished: I told them they were the pictures of some ancient and worthy Bishops, as St. Ambrose, Austin, & c.[15]

The anti-Laudian Hall, a representative at Dort, had – just like avant garde and Laudian figures – stained glass images of the saints in his chapel. What is more, when the iconoclasts moved their vandalism to Norwich Cathedral, Hall’s disgusted record of their actions reveals a material culture in the cathedral which cannot easily be distinguished from Laudian practices:

in a kind of Sacrilegious and profane Procession, all the Organ Pipes, Vestments, both Copes and Surplices, together with the Leaden Cross, which had been newly sawn down from over the Green Yard Pulpit, and the Service Books and Singing Books that could be had, were carried to the Fire in the public Market-Place; a lewd Wretch walking before the Train.[16]

In addition, Hall’s account also reminds us that the violent and extensive campaign of iconoclasm in the 1640s itself points to the widespread acceptance of images in the Jacobean and Caroline Church, inherited from the Elizabethan Settlement. The Journal of William Dowsing,[17] the Puritan appointed by Parliament to inflict iconoclasm on the churches of Cambridgeshire and Suffolk in 1643 and 1644, bears testimony to the extent of imagery in the parishes and chapels of Jacobean and Caroline Church.

Dowsing’s Journal has 223 references to “pictures,” normally prefaced by the term “superstitious”; 142 references to “cross” or “crosses”; and 48 references to “crucifix” or “crucifixes.” Individual entries in the Journal indicate not only the extent of the vandalism but, more importantly, the prevalence of imagery in Jacobean and Caroline parish churches:

Feb. the 3d, Capell. We brake down 26 superstitious pictures, and gave order to break down 6 more; and to levell the steps. One picture was of the Virgin Mary …

Brundish, April the 3d. There were 5 Pictures of Christ, the 12 Apostles, a Crucifix, and divers superstitious Pictures …

Beccles, April the 6. Jehovahs between church and chancell; and the sun over it; and by the altar, My meat is flesh indeed, and My blood is drink indeed. And 2 crosses we gave order to take down, one was on the porch; another on the steeple; and many superstitious pictures, about 40 …

Bramfield, April the 9. 24 superstitious pictures; one crucifix, and a picture of Christ; and 12 angells on the roof; and divers Jesus’s, in capital letters; and the steps to be levelled.[18]

Contrary, therefore, to Graham Parry’s interpretation in Glory, Laud and Honour: The Arts of the Anglican Counter-Reformation,[19] the campaign of iconoclasm unleashed by the Parliamentarian authorities in 1643 was not “the death sentence for all that the Laudian movement had introduced into churches during the past twenty years.”[20] Rather, it was a violent attempt to undo the acceptance of modest imagery – and the theological rationale for this – allowed by the Elizabeth Settlement and common throughout the Jacobean and Caroline Church.

Such imagery was not, obviously, dependent upon the Tridentine defense of images: indeed, this was entirely rejected. Cosin made explicit this rejection of Trent on images when he listed the differences between the Church of England (with “ancient Catholic Church”) and the Church of Rome:

That the images of Christ and the blessed Virgin and of the other saints ought not only to be had and retained but likewise to be honoured and worshipped according to the use and practises of the Roman Church and that this is to be believed as of necessity to salvation.[21]

We might note even here Cosin’s care to implicitly affirm that images “ought … to be had and retained”. What is very clear, however, is the defense of images in the life in the reformed ecclesia Anglicana presupposed an outright rejection of Tridentine teaching and practice.

Nor, however, was it dependent upon the teaching of the Second Council of Nicaea.[22] The Homily against Peril of Idolatry – invoked by Laud in defense of a modest use of images – was unsparing in its critique of Nicaea II: “an arrogant, foolish, and ungodly council.” Such criticism was repeated by those in the Jacobean and Caroline Church defending the modest of images. Lancelot Andrewes referred to the “absurd conclusions” of Nicaea II, for “this Worshipping of Images … never got sound footing till the second Council of Nice.”[23] The judgment of Jeremy Taylor was no less harsh: “superstition, by degrees, creeping in, the worship of images was decreed in the seventh synod, or the second Nicene.”[24]

Against Nicaea II, the Homily points to the Council of Frankfurt (749AD), as embodying an earlier and more modest Latin tradition regarding imagery: “the judgement of that prince [of the Franks], and of the whole council of Frankfurt also, to be against images, and against the second council of Nicaea”. In a superb article in the Orthodox Arts Journal, Peter Brooke (an Orthodox Christian painter) rejects the oft-repeated notion that Frankfurt was the result of a misinterpretation or mistranslation of Nicaea II:

the difference over veneration of images … was not just a matter of a misunderstanding due to the bad translation of the Council’s texts; nor was it a straightforward intellectual or theological disagreement … Nor was it even just a matter of politics, important as the politics were. It was also the result of a profound cultural difference, pre-existent to the intellectual quarrel, a disagreement as to the very nature and function of the visual arts.[25]

Brooke particularly points to Theodulf, a theological adviser to the court of Charlemagne and later Bishop of Orleans, as articulating the Carolingian view of religious art:

Religious imagery can be helpful but it is not necessary and certainly should not be regarded as an object of veneration nor is there any indication that the organisation of shapes and colours can be seen as a useful focus for religious contemplation. Theodulf insists that the Christian mysteries must be contemplated in the heart not through the eyes.

To dismiss this approach to imagery as ‘merely decorative’ is, says Brooke, to entirely misunderstand it:

the human need for decoration is profound and goes very centrally to our conception of what human nature is. The task is to turn a given space into a source of delight. To do so it obviously has to correspond to our human nature. A frivolous decoration implies a frivolous idea of human nature. A profound idea of human nature – for example the idea that the individual human soul is immortal and our passing life in time and space opens out into Eternity – will give rise to a profound decoration.

This early Latin use of images coheres with the practice and theology of the Jacobean and Caroline Church, in which defences of a modest use of imagery referred to the Council of Frankfurt as a means of invoking the earlier Latin practice. We see something of this in Taylor’s words that “this general council of Nice … was condemned by a general council of Frankfort, and generally by the western churches” (emphasis added). After the early Latin example, imagery in the Jacobean and Caroline Church was not for purposes of veneration but a profound decoration, encouraging the heart to contemplate the mysteries of salvation.

Conclusion

If, as Diarmaid MacCulloch has said, a “gleeful destructiveness” accompanied the iconoclasm of the Edwardine Reformation, in which initial “official attempts to reprove iconoclastic enthusiasm” were quickly revealed to be “no more than temporary window-dressing,”[26] the Elizabethan Settlement – as John Donne highlighted – embodied a significantly different approach to imagery and iconography. The Edwardine Reformation enthusiastically followed Zurich on the matter of images: the Elizabethan Settlement was much closer to Wittenberg.

Donne’s defense of modest imagery therefore invoked the fact that images “are in the greatest part of the Reformed Church,” a clear reference to the Lutheran churches, an emphasis also echoed in the Laudian Heylyn’s history of the Reformation, which noted that “shrines and images” were “still preserved in the greatest part of the Lutheran churches.”[27] The defense of imagery articulated both by Conformists and avant garde opinion – an acceptable means of putting us in mind of spiritual truths – also echoed Lutheran teaching. Donne’s assertion that images were “remembrancers of that which hath been taught in the pulpit,” and thus “they may be retained,”[28] followed Luther’s insistence that while the worship of images was contrary to the Gospel, “images for memorial and witness, such as crucifixes and images of saints, are to be tolerated … And they are not only to be tolerated, but for the sake of the memorial and the witness they are praiseworthy and honourable.”[29]

The practice and theology of imagery established by the Elizabethan Settlement and found in the Jacobean and Caroline Church was, therefore, another similarity between the reformed ecclesia Anglicana and the Lutheran Churches of the Northern Kingdoms.[30] Here was a retrieval of that earlier Latin tradition[31] (quite distinct from both Nicaea II and the Tridentine theology of images) of profound sacral decoration, an expression of a reformed Catholicism.

This practice and theology of imagery also reveals the deep roots of contemporary Anglican iconography: stained glass windows of Our Lord, Our Lady Saint Mary, the Saints and Angels; cross or crucifix on the altar; imagery on the reredos and altar frontal; pictures or icons of the events of or witnesses to our salvation; and, indeed, statuary, after the example of that of the Blessed Virgin and Christ Child installed over the porch of Saint Mary the Virgin Oxford in 1637, removed under the Commonwealth in 1651, and restored in 1673.[32]

Such profound decoration, native to the Anglican tradition and standing in continuity with earlier Latin thought, serves the faithful in calling the heart to reverence the mysteries of our redemption. We, after all, are no iconoclasts; we quarrel not the making of images, either for the public decoration of churches, or for private use.

Notes:

- See The history of the troubles and tryal of the Most Reverend Father in God and blessed martyr, William Laud, Lord Arch-Bishop of Canterbury. ↑

- Fr. Daniel Logan, ‘In Defense of Images’, North American Anglican, November 5 2021. ↑

- Op.cit. ↑

- Two Answers to Cardinal Perron and Other Miscellaneous Works of Lancelot Andrewes (1854), p.32. ↑

- ‘Offenders of the Second Commandment’ in ‘A Collection of Private Devotions: in the practice of the Ancient Church, called the Hours of Prayer’, The Works of the Right Reverend Father in God, John Cosin Volume II (1845), p.114. ↑

- ‘A Paper Concerning the Differences in the Chief Points of Religion Betwixt the Church of Rome and the Church of England Written to the Late Countess of Peterborough by Dr John Cosin, Afterwards Lord Bishop of Durham’ in The Works of the Right Reverend Father in God, John Cosin, Volume IV (1851). ↑

- From Taylor’s discussion of the Second Commandment in The Rule of Conscience, Book II, Chapter II, Rule VI. ↑

- A gagg for the new Gospell? (1624), Chapters XLIII and XLV. ↑

- From the ‘Premonition’ (1616) of James VI/I, a preamble to his Apology for the Oath of Allegiance (1609). ↑

- From Donne’s sermon on Hosea 3:4, preached at St. Paul’s Cross, May 6 1627. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Peter Heylyn, Ecclesia Restaurata (1661 – 1849 edition), Volume II, p.301. ↑

- Ibid., p.338. ↑

- Charles Prior, Defining the Jacobean Church: The Politics of Religious Controversy, 1603-1625 (2005), p.262f. ↑

- Joseph Hall, Bishop Hall’s Hard Measure, written by himself upon his impeachment of High Crimes and Misdemeanours, for Defending the Church of England (1710 edition), p.15. ↑

- Ibid., p.16. ↑

- The Journal of William Dowsing, Parliamentary Visitor for Demolishing the Superstitious Pictures and Ornaments of Churches &c., within the County of Suffolk, in the years 1643-1644 (1885). ↑

- Ibid., p.15ff. ↑

- Graham Parry, Glory, Laud and Honour: The Arts of the Anglican Counter-Reformation (2008). ↑

- Ibid., p.188. ↑

- ‘A Paper Concerning the Differences in the Chief Points of Religion Betwixt the Church of Rome and the Church of England Written to the Late Countess of Peterborough by Dr John Cosin, Afterwards Lord Bishop of Durham’ in The Works of the Right Reverend Father in God, John Cosin, Volume IV (1851). ↑

- We must note at this point that Anglican-Orthodox ecumenical discussion and agreements have provided something of a different context for the reception of Nicaea II: see particularly The Dublin Agreed Statement (1984) of the International Commission for Anglican–Orthodox Theological Dialogue. ↑

- Lancelot Andrewes The Pattern of Catechistical Doctrine (1675 edition), 2nd Commandment, Chapter III. ↑

- Jeremy Taylor, A Dissuasive from Popery, Book II, Section VI, ‘Of the Worship of Images’, in The Whole Works of the Right Rev. Jeremy Taylor (1828), Volume XI, p.146. ↑

- Peter Brooke, ‘The Seventh Ecumenical Council, the Council of Frankfurt & the Practice of Painting’, Orthodox Arts Journal, July 16 2017. ↑

- Diarmaid MacCulloch Tudor Church Militant: Edward VI and the Protestant Reformation (2001), p.71f. ↑

- Peter Heylyn, Ecclesia Restaurata (1661 – 1849 edition), Volume I, ‘To the Reader’, p.vi. ↑

- Donne ibid., sermon preached at St. Paul’s Cross, May 6 1627. ↑

- See Luther in Against the Heavenly Prophets (1525): “And I say at the outset that according to the law of Moses no other images are forbidden than an image of God which one worships. A crucifix, on the other hand, or any other holy image is not forbidden. Heigh now! you breakers of images, I defy you to prove the opposite!”. ↑

- For further exploration of this theme see ‘More Laud than Baxter: the Protestantism of 1662’, North American Anglican, November 22 2021. ↑

- Ratzinger describes this early Latin tradition in contrast to Nicaea II: “if we think of St. Augustine or St. Gregory the Great, the West emphasized, almost exclusively, the pedagogical function of the image … the western synods insist on the purely educative role of the images”. See Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy (2000), p.125. ↑

- As Laud noted at his trial, when the statue was raised against him, “never did I hear any Abuse” in terms of misuse of the statue. A fine contemporary Anglican example of a statue of the Blessed Virgin and Christ Child is that in Lincoln Cathedral, created by Orthodox iconographer Aidan Hart. See Hart’s discussion in ‘Our Lady of Lincoln Sculpture’, Orthodox Arts Journal, June 17 2014. ↑

'“I quarrel not the making of images”' have 11 comments

January 25, 2022 @ 9:16 am Joseph Mahler

The second commandment is quite clear and should be taken as absolute law. Violation of it is sin and repugnant to God. The above article tries to make images in churches seem okay and in accordance with the Homily Against the Peril of Idolatry. However, the homily taken in its entirety certainly forbids the use of images/idols in churches. The homily makes no distinction between image and idol. The reintroduction of crucifixes and processional crosses with corpus demonstrates that this reintroduction is in fact against the second commandment and the homily, for members of the congregation bow before both. All images of Christ (God the Son) are false and all are images of deity which is strictly forbidden by the second commandment. Hugh Latimer well wrote this, “Where the devil is resident, that he may prevail , up with all superstition and idolatry, censing, painting of images, candles, palms, ashes, holy water, and new service of men’s inventing.” Latimer was martyred in the flames of Marian fire for his defense of Biblical truth and practice.

January 25, 2022 @ 2:03 pm Christian Cate

With respect, perhaps you would be more at home in the Evangelical Presbyterian Church. Anglicanism as it is now what is regarding these matters and it won’t be returning to the condition you suggest here.

Processional Crosses and adornments are here to stay. To try to turn back the clock now would only divide further the Global South and the ACNA. To attempt such a change would be tilting at windmills at this point

January 25, 2022 @ 2:18 pm Joseph Mahler

Christian Cate, thank you very much for telling me that the Church that I was born in and raised in that I am no longer welcome in. No, the Anglican Church must define itself. It cannot be anything goes. That would be the world not Christianity. Anglicanism is easily defined as the Church of the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion, the two Books of Homilies, and Prayer Books that conform to the doctrine of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. Anything else is pseudo-Anglicanism. I am not a member of the ANCA or of any church that ordains women to the ministry. Idolatry is forbidden by Holy Writ, please spend the time to read the Homily Against the Peril of Idolatry. It is genuine Biblical, Christian, and Anglican doctrine. May God melt the stony hearts of them that hold His Law in contempt.

January 26, 2022 @ 9:21 am Connor Perry

This is a strange comment, to say the very least. As telling a man to “go become an ‘evangelical’ Presbyterian” (whatever “evangelical” means in such a context) for arguing a more Lutheran position on the retention of images is bizarre.

The additional comment of “Anglicanism as it is now… won’t be returning to the condition you suggest here” is especially bizarre, as the theology expressed here (modest imagery acceptable, Nicaea II not so) is not something rare or even uncommon to find in Anglican Churches.

Furthermore, on the note of the ACNA, if we wish to be a healthy, God-fearing communion of saints, we should be very clear about the discipline that we have already established by accepting the 39 Articles as authoritative. If you’re afraid of schism because you would be enforcing pre-established rules, this shows that the very communion is spiritually unhealthy and not in proper submission and charitability to higher ups. If it was something alien being enforced on a priest, schism should be expected, but if it is something very much pre-established as being enforceable finally being enforced, I do not see how one could avoid charges of contumacy and needless schism that would result from not accepting such discipline.

January 26, 2022 @ 12:07 pm Christian Cate

The Evangelical Presbyterian Church and the Presbyterian Church of America are fine, conservative Christian denominations. They are less “catholic” however than the ACNA in form, yet even they have stained glass, candles and crosses in their congregations. They sometimes process into their churches with fully robed choirs and bagpipers.

Then again, some EPC congregations in form are not much more than Community Churches.

My point was that the ACNA will never return to a time of stripped altars and the iconoclasm of the Roundheads and Cromwell’s “glorious revolution” even with better enforcement of the 39 Articles.

As in regards to the 39 Articles, historically the Anglican Church had even more Articles that were later reduced to the 39 in effect today. The Articles can and should be amended to allow for a more Eastern Orthodox view of images, at least at the level of the laity.

Of course the Roman Catholic distortions and errors should never be allowed. Those beliefs are indeed distortions and errors. Roman Catholic abuses don’t justify rejection of Eastern Orthodox beliefs and practices, as these are different. Equating Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy is a major error Anglicans often make.

Amend the 39 Articles to include the new information that has come to light since the Reformation by Anglican exposure to the Eastern Orthodox. The current 39 Articles are outdated on these matters and there is no longer an excuse to maintain parts of them that are themselves erroneous.

So I am indeed calling for a careful amendment to the 39 Articles. Surely there is such a process?

Some of my comments might seem bizarre to you, but when I was writing them, I was recovering from surgery.

I’m spiritually “of the half tribe of Manasseh” at present, attending an ACNA parish in the International Diocese while being a member of a Western Rite Antiochian Orthodox parish that used to be an Episcopal church. Family matters have necessitated this circumstance. So I live in both worlds.

The Grace within the Orthodox Church is real, however, and bears a closer look by the entire ACNA and conservative Anglicans in the Global South. Both Communions can benefit by continued patient, and prolonged exposure to one another, and throw the G-3 Anglicans into this mix as well.

Blessings,

Reader Columba Silouan

January 26, 2022 @ 12:38 pm Joseph Mahler

“My point was that the ACNA will never return to a time of stripped altars and the iconoclasm of the Roundheads and Cromwell’s “glorious revolution” even with better enforcement of the 39 Articles.”

Uh! The ACNA has never been any of these things. It is an amalgamation of churchmanships and doctrines of diverse places from the middle ages to the charismatic movement. It is a rather new denomination. It has very little to do with historical and true Anglicanism.

The Church of England and Anglicanism did not ever depart from Catholic Church. With the reforms, going back to the original form of the primitive Church and shedding the abuses and paganism and idolatry that has grown up in the Eastern and Western Churches, Anglicanism became more Catholic. The traditions of man and outright sin against God’s Law cannot be deemed Catholic but rather apostasy, heresy, and outright diabolical. It is not the 39 Articles which are in need of revision but rather the souls, hearts, and minds of men.

This history of the Seventh Council is somewhat dirty. Elena was no saint. and btw the anti seeond commandment 7th council has never been ratified by a subsequent council as is required by the Eastern Churches.

It is obvious that you have been influenced by non-Anglican influences and that you are not Anglican. You reject the 39 Articles and the Books of Homilies which are established by the Articles of Religion as doctrine of Anglicanism. You are in the company of them that hold tradition on the same level with Holy Scripture and reject the teachings of Latimer. Teachings that he was willing to die for. You also appear to me to be one who is not Anglican by raising, but one who would exclude from Anglicanism one who is. This is sad. I have often been lectured to as to what is Anglicanism by proselytes who want to be Anglican but keep their old church doctrines. It is the attitude of “I am more Anglican than thou.” I get tired of it. Anglicanism needs to get back to it roots in the Reformation, strive to become that pure Church that is acceptable to God. Anything else is a waste of time.

January 26, 2022 @ 12:59 pm Christian Cate

You’re correct. I’m Eastern Orthodox with an affinity for all that is truly good and beautiful and true in Anglicanism. So you might say I’m an Anglican Sympathizer. I was “fully Anglican” for a period of time, in the Episcopal Church pre-Gene Robinson, then in the AMIA.

But I left Anglicanism for Eastern Orthodoxy fourteen years ago after some disappointments with the local AMIA parish we helped to plant.

To be fair, I already had more “catholic” leanings and exposure from a stint in the Charismatic Episcopal Church.

But I rejected Rome as an option due to my exposure to Anglicanism and Eastern Orthodoxy. We did spend a year in a fine LCMS Confessional Lutheran Church as well before my Eastern Orthodox conversion.

Then again, I started out my journey as a Baptist before any of this.

And went through a C.S. Lewis styled “reluctant Charismatic” period when I became convinced that the Gifts of The Spirit were indeed operative today on the basis of Renewal Theology arguments presented at Regent University in Virginia Beach.

These types of journeys really are unavoidable in the current Christian world we all live in.

Christian Identity Politics really work no better then Secular Identity Politics, let’s just leave it at that, I suppose.

I’m an Orthodox Anglicanesque Christian, praying the BCP / Liturgy of Saint Tikhon constantly and singing glorious hymns out of the 1940 Hymnal once a month. A Goodly Heritage indeed.

January 26, 2022 @ 1:12 pm Christian Harwood Cate

By the way, martyrdoms go both ways, Archbishop Laud was also killed, as was King Charles the First. None of these killings should have happened. Hopefully we’ve learned from these blots on our shared history.

My middle name is Harwood, which is an ancient English name going back to before the Norman Conquest. My loyalty to The English Church has very deep roots, whether I pass the current Anglican Smell Test or not.

I’m an English Orthodox Catholic Christian, and may it ever be so!

January 26, 2022 @ 9:22 am Connor Perry

Good article! Very well researched and written.

January 26, 2022 @ 12:45 pm Daniel Logan+

Thank you for this, Father Laudable. 🙂

February 22, 2022 @ 10:55 pm Morgan

An excellent article that just when I think I knew anglican history I cant put this one down. Keep up the great work.