In case you’ve been living under a rock, Hillsong is in trouble. While the superstar pastor Carl Lentz fell from grace back in 2020, now several other scandals have arisen, including the “global pastor” Brian Houston resigning due to breaking the church’s code of conduct. Members, pastors, and entire congregations are leaving. The Hillsong leadership is clamoring for NDA’s and non-compete clauses. It’s a mess.

But it’s a mess that implicates the entire evangelical world, especially as found in the West (but exported to the global Church). After all, one of the reasons Hillsong is so prosperous is because people keep sending them music royalties. For some reason (still lost to me), people love Hillsong’s product, and they like featuring that product in their church worship services. If you’re the sort of person that reads this fine publication regularly, you probably have strong opinions on why that’s a problem and where much of the problem stems from.

Critics (including yours truly) mock Hillsong and its copy-cats for working hard at making Christianity cool, even though the world will never accept orthodox Christianity. Our culture is enamored with sexual license and its associated maladies, and no amount of cool factor is going to garner much goodwill, loyalty, or respect. The attacks against Hillsong by anti-Christian pundits have been just as vicious as those against the Roman Catholic hierarchy and the Southern Baptist Convention.

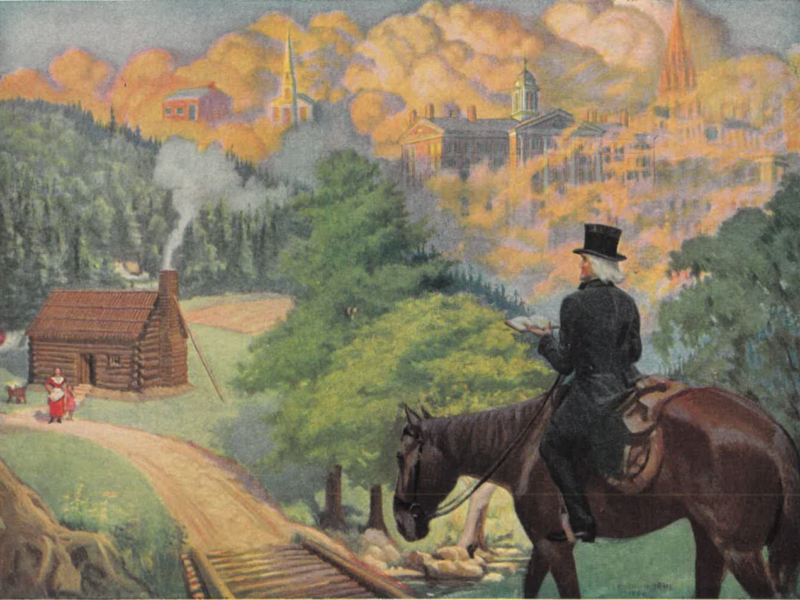

It’s sad, really. All the effort, thought, talent, time, money, and other resources spent on appealing to the world result in no love from the world. Meanwhile, the sheep of the flock (or worldly people who are into “spiritual” things) get malnourished and malformed. There shouldn’t be a thin line between the Spirit’s moving and an emotional high artificially manufactured by certain chord progressions, nor between a pastor and a high-flying CEO. For the first, churches need to stop attempts at engineering conversion or, perhaps these days, a great feeling of “spirituality” through concert-like worship services. This erroneous assumption goes at least as far back as Charles Finney and was roundly criticized by John Williamson Nevin’s The Anxious Bench. For the second, biblically-qualified men can buckle under the pressure of performance anxiety and temptation while narcissists find attraction in fame and spiritual power. Hillsong is just the latest organization to have incorporated industrial entrepreneurship with individualistic religion, creating an unmistakably “cool” brand.

After all, Hillsong’s coolness is established by generating emotions through a specific form of music, preaching, teaching, and overall “church experience” that is utterly devoted to correct feelings. As some have quipped, evangelicals these days aren’t so much governed by orthodoxy (right doctrine) but rather orthopathy (right feeling). If those feelings aren’t present, the worship isn’t “Spirit-filled” and one’s spiritual life must be lacking. Moreover, spiritual health is to be found in those things which emotionally delight us.

Hillsong has mastered the creation, distribution, and even sale of this therapeutic lifestyle brand to the current generation. That’s what makes them so special or unique. Boomers and Gen-Xers loved “Shout to the Lord” while Millennials and Gen Z have embraced “Oceans.” But just because Hillsong was on the cutting edge of these trends—awash in money, members, “cool factor,” and adulation—does not mean the rest of Christianity escapes criticism. All religious groups are struggling with what Philip Rieff termed the “triumph of the therapeutic.”

That includes our own tribe, in all honesty. One would think that Anglicans—particularly conservative evangelical Anglicans who love the English Reformation—would be all about Archbishop Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer. After all, this was the man who was martyred for his convictions. His liturgy is by far the most dominant in Anglophone Protestantism. And, as we like to talk up all things liturgical in the Anglican world (especially when giving an elevator pitch), you would expect Cranmer’s words presented at least every Sunday in evangelical Anglican parishes across the United States. You would be wrong. Usage of Cranmerian Prayer Books like the 1662 and the 1928 are hard to find. As one evangelical Anglican told a colleague, he preferred newer prayer books “because they’re happier.”

Let that sink in. An evangelical chooses the fruit of liturgical revisionists over and against the fruit of the Reformation he so loves to praise. And the doctrines which traditional evangelical churchmen have long embraced and advocated are found with greater clarity in the Cranmerian liturgies. But they aren’t “happy” enough. From the mid-20th century on forward, the immense gravity of Cranmer’s Prayer Book, Coverdale’s Psalter, and the Authorized Version of the Bible have given way to cheerier texts that are more “approachable,” downplay our wretched sinfulness, and de-emphasize Christ’s propitiatory sacrifice on the cross. Why would a Reformational evangelical ™ choose the thinner gruel of post-Dixian monkeyshines over such a goodly heritage? Because they value something that isn’t found in the classical prayer books—the right feeling, which often involves a sunnier language with regard to sin, God’s judgment, and the dreadful sacrifice necessary to save sinners from said judgment.

This liturgical preference is part of a wider aesthetical one. It manifests in horizontal architecture, a stage-like chancel dominated by contemporary musical instruments, and the all-present projector screen. Even when parishes have more than adequate resources to purchase good hymnals and prayer books, they opt for the “mene mene tekel upharsin” on the wall. Even when congregations or their ministers could afford traditional vestments, they opt for tailor-made suits, colorful clerical shirts, and maybe a stole. Throw in some lightweight preaching, and we are off to the races. So we have Anglicans who don’t like the clothes that Anglicans traditionally wear and don’t like the songs Anglicans traditionally sang (or at least hold them in the same esteem as Hillsong industrial pablum). Even in a synodal context, when we aren’t trying to put on an “attractional” show to the de-churched and “seekers,” we can shy away from the full Anglican patrimony.

Why? What are we allergic to? What are we avoiding in these small renunciations of tradition? Taken individually, these are unimportant peccadilloes. Taken as a whole, there’s something bigger and nefarious going on here. A revolt against a certain aesthetic is afoot, even as that revolt may be inherited from the wider Big Box evangelical culture rather than from within Anglicanism itself. The bastardized result of mixing the Anglican heritage with consumerist revivalistic evangelicalism is an example of what one priest termed “Cheez Whiz Anglicanism,” and the label fits. “It looks something like cheese (old school Anglicanism),” he pointed out, “but it really isn’t.” But why? Why opt for Cheez Whiz over the real thing?

For the most part, it’s because we’re hooked on something, like an addict to a drug. We are addicted to the therapeutic. And it’s a manifestation of a more fundamental spiritual problem: a widespread rebellion against hierarchy. “Dour” vestments and clericals, militant or contemplative hymns that don’t give a U2 or Coldplay “vibe,” majestic courtly language in Scripture and liturgy, traditional church architecture (from the small country chapel all the way to Wren and the neo-Gothics), and straightforward preaching of unpopular truth are for therapeutic evangelicals what the “patriarchal, metaphysical god of the Old Testament” is to liberal academic theologians. We suppress anything that could imply that we have “betters” even in this mortal life that are to be honored and obeyed. We are all interchangeable blobs, and the only earthly things (if any) that have legitimate authority in our eyes are bureaucracies. As for the Lord, we redefine and reimagine Him. We squirm at the thought of a truly transcendent, awesome, impassible, simple God Who’s not our empathetic psychotherapist but instead the One Who can deliver us, according to His wisdom, power, and goodness (a point that E. L. Mascall makes with great potency in his Christ, the Christian, and the Church).

Contemporary man does not want authority from “on high,” even if that is the great Author of all Himself. The traditions of our fathers must be trashed. Catechesis—the “sounding down” of the faith once delivered—cramps our style. It’s all slow growth, and it all requires us to honor our betters. That’s profoundly unappealing. Perhaps most important of all, gravity must be repudiated with all our might and main, especially in the assembled service of worship. We must always be drifting on a cloud of good feelings, perhaps with near-nonstop atmospheric background music. This is not just a megachurch problem. Many conservative Anglican churches simply cannot resist a “floaty” worship service.

We can get very sensitive when our therapeutic, egalitarian values are questioned or criticized. We have reduced the faith to what we think or feel inside with little thought to external realities breaking in or being participated in. After all, what often is the sacramental theology of the emotionalist? As one seminarian asked in a church history class, “Why were Luther and Calvin talking about baptism and the Lord’s Supper all the time? Did they just not have good teaching?” While that young man got a good dressing down from his professor, other parts of the Christian world wholeheartedly embrace such an interior-emotions-abstract orientation when it comes to the faith. It appeals to the dominant outlooks of our day. And Anglicans that, for whatever reason, find themselves enamored with the Hillsongification/Saddleback-ification/Willow Creek-ification of the Church need to take a step back. How far are we going with this attractional approach to liturgical expression? Why are we indulging it at all? Where does it end up? Shouldn’t we renounce this as spiritually unhealthy and un-Anglican?

Of course, when we start talking that way, we find ourselves booted from the cool kids table, as one writer has put it. We are cranks; we are defeatists; we are narrow-minded; we can’t plant and grow thriving churches. However, as D. G. Hart has convincingly argued, the liberalization of America’s Protestant churches was not the result of crazed heretical radicals. Those were on the fringe. The rot resulted primarily from broad evangelicals who did not care about confessional commitments, liturgical heritage, and church discipline within their own denominations. These narrowing characteristics rocked the boat too much and excluded certain people. They threatened the pan-evangelical American social project. Perhaps worst of all, they could involve renunciation of things that feel good and are popular.

And it’s just that kind of ascetical resolve we need if we’re going to weather our current cultural storm. We, our children, and our grandchildren need to be preaching and living the faith once delivered to the saints decades and even centuries from now. For generational continuity and for Anglican orthodoxy to exist once we are out on the other side of the season of insanity, we need a strong commitment to the catholic deposit of faith, especially as expressed in our unique patrimony. If those things are suppressed, ignored, or avoided, we should not be surprised with a repeat of Mainline infidelity with regard to doctrine and moral teaching. So let us make perfect our will.

'Hillsong and Cheez Whiz Anglicanism' have 7 comments

April 4, 2022 @ 11:22 am Lawrence+

It’s been stewing quite a while. If you read Chorley, one of the editors of the 1928, as to why certain liberal revisions and deletions were made in the 1928, some of it was because they were progressives, sure, but some was because they found the prayerbook depressing with all that talk about sin.

April 4, 2022 @ 1:58 pm James Coder

Thanks so much for your exposure of the problem of “correct feelings” in American church practice and tacit belief.

I have been trying for ages to “wake up” Anglican clergy to this issue, which is soooo helpful in pointing people to the direction of good liturgy. But there has been lots of resistance. I’m not a Christian celebrity and this might “not be relevant” – you know, I can’t tell you in five minutes where it is in the Bible, and it takes some TIME to explain, and everyone these days has got to be with their kids, and et cetera et cetera.

Basically, we’ve been speaking for ages about orthopraxy and orthodoxy, and somehow missing the boat despite all our talk. Some call themselves more “orthopraxis oriented” – others are “orthodoxy oriented.” So then voila: somebody solved it!! Lots of songs about how we FEEL. That … kinna ties the two together right? That must be like – way deeper, right? And it is totally consonant with American Romanticism, which most of us are – so it’s super-duper popular and understandable and it’s easy to make a lot of Scripture look like it’s all about various kinds of feelings.

So you get orthopathetic legalism – or orthopathetic fundamentalism. You better have the right feelings or you’re not a good Christian. We need to shape our lives to have the right feelings, or out of expectation of others’ feelings, or at least their projected / pretended virtue-signalling “feelings.” And we’re off to the races.

A lot of Christian practice and teaching these days seems to imply this. Cary’s book Good News for Anxious Christians tries to deflate that we “need to feel God’s love.” I’d LOVE to collaborate with you somehow to try to get this FURTHER understood by Anglican clergy, this could go a very very long way toward helping the church REFORM. If you friend me on Facebook, you can find lots of stuff I’ve written on the problem of orthopathetic fundamentalism by searching FB for “orthopathetic.” I am interested in speaking with anyone who is rather serious about this topic as it is a very important issue for a prayer group / incubation group that I’m a part of.

But KUDOS to you for highlighting this as a really essential thing we need to be seriously confronting, and NOT conforming our teaching to. I fear lots of Anglican clergy have already shaped their world view more or less to accommodate this, and are preaching in ways that also accommodate this. This is falling prey to the principalities and powers, and implicitly encouraging others to do the same. It’s also spreading folk theology.

Blessings,

James Coder

April 9, 2022 @ 4:10 pm Charles Sutton

A very astute analysis! The trouble is that many of the younger clergy were raised in feelings-focused congregations, and that is what they know and seek to reproduce. I have known one young Anglican pastor who interrupts the service to cheerlead, or to praise the congregation for their enthusiasm. Being feelings focused does not help, even if it does draw people in from a society that has been focusing ever more closely on the lie that one’s feelings and inner self are the measure of truth and goodness. Where the focus is not outward, on the God of heaven and earth, we run the risk of either orthopraxy or orthopathy – or both.

April 4, 2022 @ 3:19 pm Sudduth Cummings

Amen and pass the alms basin! You are right on target with your analysis and its what I’ve thought since entering Anglicanism via the Episcopal Church in 1964 (yes, I’m in the senior citizen stage.) Enduring the “happy clappy” phase of music and worship never challenged my commitment to the Anglican tradition, but the 2979 BCP of TEC was a huge mistake. The ACNA BCP is a vast improvement even with carrying over a bit too much of the ’79. I still enjoy the last classic prayer book in the 1928 which brought me into this tradition. And I pray for a renewal of orthodox faith and practice.

April 4, 2022 @ 11:06 pm Jennifer Thompson

Great article. Thanks for sharing! Is there a directory of Anglican churches that user the 1928 prayer book? How does one find a church with good liturgy? My family and I are considering moving. I’d love to go somewhere where I can find a church that has good liturgy and hasn’t completely succumbed to the trends you describe in this article. It feels like looking for a needle in a haystack.

April 5, 2022 @ 9:04 am Mark Perkins

Thanks for this, Fr. Bart. I think you’re right on every count.* Of course, the more sincere and thoughtful among the Cheez-Whizzers would argue that the evangelical imperative requires adaptation and contextualization. And while I think they’re dead wrong at the end of the day, they aren’t totally nuts to think the way they do. They have two basic points in their support that we have to take seriously:

(1) The crude numbers game, but with qualification. I don’t think the size of Cheez-Whiz churches is generally in their favor, actually — a parish of over 500 is a mistake, not a success. And Cheez-Whiz churches are either bigger than 500 or aspiring to be bigger than 500. But they do have a point when they, uh, point to our churches (broadly meaning parishes using pre-1979 liturgies). Can parishes using traditional liturgies thrive or even survive? On the one hand, I absolutely know they can — I’ve served in two such thriving parishes — but the bigger picture does not exactly robustly support my anecdotal experience. Many major metropolitan areas (not to mention everywhere else) lack a decently healthy parish using traditional liturgy. What good does it do to be on the side of the angels if you can’t attract any human beings?

(2) More anecdotally, some of our best parishioners and clergy were drawn to the Anglican tradition via Cheez Whiz, and then after some time realized what they really wanted was genuine Stilton. That wasn’t my experience — I wandered into Holy Trinity Hillsdale straight from a Reformed Baptist congregation — but it’s the experience of many, and a number of them don’t think they’d have given the real thing a chance without that waystation first. So the Cheez Whizzers could say, with some justification, that we are parasitic on the Cheez Whiz, and that without the Whiz, we’d be even more sadly situated…

Like I said, I wholeheartedly agree with your piece, but, as you note, you’re more or less preaching to the choir here. As sad and anemic as Cheez-Whiz Anglicanism is theologically and liturgically, traditional Anglicans have to deal with our own sad anemia. And at times I wonder if part of what makes us less attractive is not so much the “price of entry” of traditional language as it is just how right we know we are — and just how benightedly wrong we know everyone else is. I have, maybe, a reputation of being polemical — and I’m not afraid of polemics — but I’ll tell you that I go out of my way to undercut triumphalism in my parish at every turn, and to push us not to be fat and happy in our rightness, not to take comfort in the “narrow way” of being right but rather profoundly uncomfortable with how few people want to be right with us. Anyway, the short of it is, I would like to see “us” (if I may be so bold) be more enthusiastic in upholding the goodness, truth, and beauty of what we have, and maybe a little less into pointing out where everyone else doesn’t have it right.

Sorry for the rambling — these thoughts are perhaps a bit underdigested.

Blessings,

Fr. Mark Perkins

I’d like to figure out how it is that we can build healthy and vibrant parishes

*Well, okay, maybe I’d awkwardly clear my throat and avert my eyes amidst the paeans to the Reformation… but that’s certainly not keeping me from counting myself on your side on this (my question always being whether the Old High Church folk feel the same, but I digress…).

April 7, 2022 @ 3:37 pm James Henry White

Preach on, Brother! You have read my mind and expressed my thoughts better than I could. Well, and timely spoken.