Anglicanism and the Deuterocanonical Books

Anglicans read the Deuterocanonical books because they teach us about life, faith, and Christian manners. Article VI of the 39 Articles makes it clear that these books are for instruction, not for establishing doctrine. This reflects the early Church’s approach, where the Fathers tolerated different opinions about these books while holding firm to essentials of faith. Anglicanism continues this patristic method of restraint, valuing the guidance these texts offer without requiring doctrinal agreement.

Article VI of the 39 Articles says, “The Books commonly called Apocrypha, not being of Divine authority, are read for example of life and instruction of manners; but they are not applied to establish any doctrine.” In practical terms, the Church reads these books because they teach us how to live, provide examples of faith, and guide us in Christian manners. They help us grow, but they are not the foundation of what we must believe. Doctrine rests on canonical Scripture, not these supplemental texts.

This distinction is exactly what makes Anglicanism faithful to the patristic method of restraint. The early Church tolerated differences in opinion about these books. The Fathers valued them, cited them, and read them, but they never insisted everyone must treat them the same way. Diversity of opinion on the Deuterocanon was allowed while unity in essentials of faith was maintained. Article VI simply formalizes this approach. It confirms reading the Deuterocanon for instruction and devotion without making it doctrinal.

How the Fathers Treated These Books

The early Church did not ignore these texts. Figures like Augustine, Jerome, and Athanasius cited Wisdom, Tobit, Judith, and Sirach in sermons and letters and recommended them for moral and spiritual instruction.1 At the same time, these books were never treated as doctrinally required. Jerome preferred the Hebrew canon and expressed caution about some books. Augustine cited them frequently without making them the basis of doctrine. Athanasius included some while tolerating debate over others.2

The key point is restraint. The Fathers used these books for moral and spiritual guidance but never claimed that reading them made someone orthodox or demanded universal agreement. Anglicanism follows that same example. We read, study, and benefit from these books while keeping the focus on Scripture for doctrine.

Historical Reality Before Trent

Contrary to some assumptions, the Catholic Church did not maintain a single, universally binding Old Testament canon long before Trent. The Latin Church had a preferred list, largely based on Jerome’s Vulgate, but it was not enforced across all regions or rites even after the start of the Reformation. The wider Old Testament tradition continued in use rather than a uniform, imposed canon. Churches following Eastern traditions, such as Maronite, Byzantine, or Armenian, continued to read their own collections freely and were never required to adopt the Latin preference.3 Even within the Latin Church, clergy and monasteries sometimes read additional books or emphasized different texts for moral and devotional teaching. Differences were tolerated, and no one faced excommunication simply for reading or teaching from these books.

Several major Bibles used before and around the time of Trent retained the Deuterocanonical books in the usual Western order. Luthers Bible, which predated Trent, included them for instruction though not as doctrinal authority. The Geneva Bible, the Bishops’ Bible, and the King James Version continued the same practice. These editions reflect the longstanding Western tradition: the Deuterocanonical books were read and valued, but not elevated to binding doctrine. Anglican practice follows this historic precedent.

For centuries, the Church functioned without a single, binding Old Testament canon. Anglicanism preserves this practice. Article VI reflects it: these books are read for instruction and devotion but are not elevated to doctrinal authority.

Trent and the Shift to Uniformity

The Council of Trent in 1546 marked a major change. In response to the Reformation, the Roman Church dogmatically defined the canon and included the Deuterocanonical books. Dissent could be treated as heresy.4 Trent was legitimate for Rome, but it does not reflect the practice of the early Church. Before Trent, diversity in secondary matters was tolerated. Anglicanism maintains the pre-Trent approach. We read, study, and benefit from these books without binding doctrine.

One important difference is that post-Trent Catholicism prioritizes institutional uniformity, whereas Anglicanism prioritizes historical fidelity to the Fathers. By following the early Church’s method of restraint instead of centralizing authority, Anglicans read the Deuterocanon for instruction without requiring doctrinal assent.5

Anglican Humility in Practice

Restraint is not a weakness. Anglicanism makes a clear distinction between essentials and secondary matters. The Creeds, the doctrines of Christ and the Trinity, and the call to repentance are essential. The Deuterocanonical books, while profitable, are secondary. This mirrors the practice of the Fathers. They allowed differences on secondary matters while holding unity on essentials. Anglicanism formalizes that approach. We read, reflect, and apply these books for instruction and devotion, but we do not make them the basis of doctrine. This approach respects both history and pastoral wisdom. It honors the Fathers, values Scripture, and keeps our focus on what matters most.

Answering Critics

Some critics argue that Anglicanism is not “fully faithful” because it does not treat the Deuterocanonical books the same way as post-Trent Catholicism. They miss the point. If a universally binding canon had existed for centuries, we would expect enforcement, including discipline, excommunication, or anathema, for anyone who read or taught differently. We do not see that. Anglicanism mirrors the historical reality: the Church tolerated differences in secondary matters while preserving unity in essentials. Critics are often guilty of an anachronism. They assume Trent reflects the practice of the early Church. It does not. Anglicanism, by following Article VI, preserves what the Fathers actually did.

Conclusion

Anglicanism, through Article VI, reflects the patristic method of restraint. The Fathers tolerated differences of opinion on the Deuterocanonical books without claiming universal agreement. Anglicans read these books for instruction, moral formation, and devotion, but they do not make them the basis of doctrine. This approach preserves historical fidelity, theological clarity, and pastoral wisdom. Anglicanism does not invent a canon, nor does it reject the Fathers.

Instead, it follows the Church that was humble, discerning, and faithful to Scripture, the same Church the Fathers knew. This was a Church that allowed some variation on the Old Testament books because they were not essential to the core matters of salvation. In the end, Anglicanism shows that you can honor tradition, Scripture, and moral instruction without confusing devotion with doctrine. That is the essence of Article VI and the patristic method it preserves. Anglicans read the Deuterocanonical books as the Church always did up until the Council of Trent (1546): for instruction and devotion, not as required doctrine. We follow the patristic way of looking at these books. We are not doing something new.

Notes

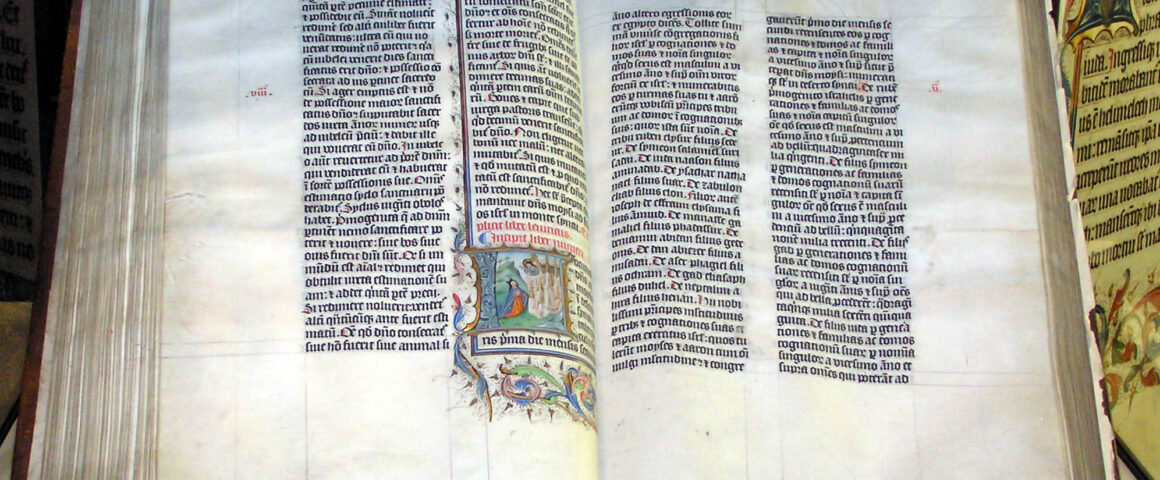

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

1. Augustine of Hippo, On Christian Doctrine, Book II, Chapter 8, in Nicene and Post‑Nicene Fathers, Vol. 2, translated by J. H. Newman and W. J. Tyrrell (Hendrickson Publishers, 1997).

2. Jerome, Prologus Galeatus to the Books of Kings, in Select Works of Saint Jerome, translated by W. H. Fremantle (Baptist Mission Press, 1888).

3. Bruce M. Metzger, The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 51–60.

4. Council of Trent, Decree on the Canon of Scripture, Fourth Session, April 8, 1546, in J. Waterworth, The Canons and Decrees of the Sacred and Oecumenical Council of Trent (London: Dolman, 1848).

5. Council of Trent, Decree Concerning the Edition and Use of Sacred Books, Fourth Session, April 8, 1546, in J. Waterworth, The Canons and Decrees of the Sacred and Oecumenical Council of Trent (London: Dolman, 1848).