Gerald Bray’s new Anglicanism begins with a chapter spelling out succinctly the history of the Church of England, its sisters, and successors until the middle of the Nineteenth Century. The Anglicanism of the early twenty-first century, Bray notes, “is essentially a nineteenth century invention.” Before the 1840s most members of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States, the Church of England, the Church of Ireland, and the Scottish Episcopal Church saw themselves as members of Protestant bodies that “separated from Rome in the sixteenth century along with several other churches in Northern Europe.” Churchmen in England and Ireland knew that the “details of the separation were unusual,” that they retained a formal episcopate, and that included political considerations affected the separations from Rome, but the basic principle—that the Churches of England and Ireland were Reformed churches—was never contested until the Tractarian innovations of the mid-nineteenth century. “Almost all members of the Church of England”—and perhaps literally all members of the Church of Ireland—”saw themselves as Protestant and Regarded Rome with varying degrees of enmity.”[1]

The assumed Protestant and Reformed nature of the Episcopal Church in the United States remained uncontroversial during the first half-century of the life of the American Republic. Polemical questions over the place of Protestant particulars appeared non-controversial. Questions over rule of worship and ecclesiology divided Episcopalians from their Protestant brethren. The assertion that Anglicanism represented a sort of “third way” of Christianity that was neither Roman Catholic or Protestant would have been seen as historically contrived and intellectually unserious. The Church of England, organized and created more by Edward VI, Cranmer, and the Book of Common Prayer in the 1550s than by Henry VIII, affirmed the great Lutheran declarations of the early Reformation but used most of its energies to fight the battles of the second generation of Reformers. The distinction between Law and Gospel that Luther prized was assumed; Anglicans had other things to argue with fellow Protestants and Catholics about over the course of the next century. Ecclesiology, for example, proved to be the great rock on which British Protestantism crashed in the Seventeenth Century. Neither the Cavaliers nor the Roundheads debated Law and Gospel as they killed each other during the English Civil War. The contrived and falsified histories of British religion perpetuated by non-conforming Puritans of the seventeenth century and by Tractarians in the nineteenth eventually hid entirely the Church of England’s substantive ties to Continental Reformed and Lutheran state churches during and after the Reformation; the theology of the Church of England rested firmly in Luther’s Solas.

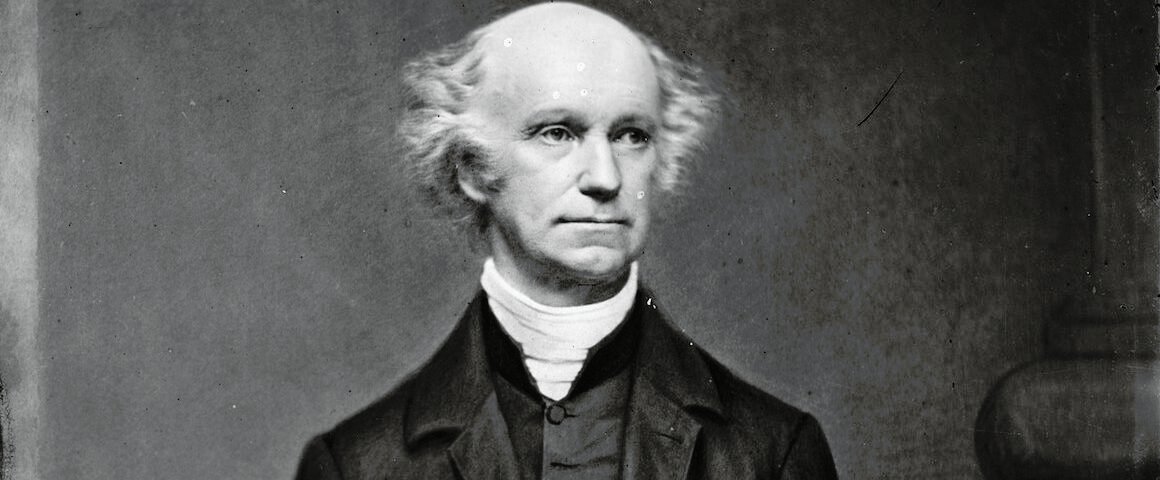

The great soteriological tie between Anglicans, Lutherans, and Calvinists remained the understanding that sinners were saved by grace through faith, and their merit played no part in their justification. Charles P. McIlvaine, Bishop of Ohio, used his pulpit in the aftermath of the Tractarian controversy to posit the traditional Anglican position that in some ways was more committed to Luther’s Law/Gospel hermeneutic than Calvinists in the era were. McIlvaine felt strongly enough about the Lutheran roots of Cranmer’s articles to note that “a frequent correspondence on the most important matters of the Reformation was kept up between Cranmer and the continental Divines, especially Melanchthon.” The Lutheran luminary, in particular, the bishop explained, was “particularly consulted on the subject of the Articles, and is known to have urged for a model, the Confession of Augsburgh.” Hence the Articles of the English Church “chiefly derive their origin from Lutheran Formularies.”[2]

McIlvaine lived in an era where Protestants in the United States shared a broad orthodoxy on soteriology even as they disagreed on ecclesiology, the sacraments, and the rule of worship. Distancing the Episcopal Church from other Protestants did not pay a social dividend. McIlvaine himself hailed from patrician stock. Peter Toon called him “an aristocrat by birth and bearing and a bishop by consecration of the Episcopal Church.” McIlvaine “knew himself to be a common sinner in God’s sight, as much in need of rescue as the folk to whom he ministered.” McIlvaine affirmed Charles Le Bas who argued that the “English Reformers framed their Articles not as a wall of partition between Protestant and Protestant, but as a bulwark against the perversions with which the scholastic theology had disfigured the simplicity of the Gospel.” The key to unlock the true sense of the Articles, McIlvaine argued was “a knowledge, not of the opinions which afterwards rent the Protestant community into fragments, but of the papal doctrines against which the main struggle of the reformers had been carried on from the very first.” The reason for the Church of England’s existence as a Reformed body on the island of Great Britain, and the reason why Edward VI and Cranmer set about creating their prayer book to actualize Protestant life in England, was not to perpetuate a distinct form of the British or Sarum[3] rite, to preserve the episcopacy for its own sake, or a certain socio-cultural aesthetic. It was, declared McIlvaine, “the single pretense of the sinner’s own merits or righteousness, entering into the justification of his soul before God, that kindled their united and stern hostility.” McIlvaine forcefully dismissed the musings of Richard Hooker on a potential secondary justification. “There seems no room in this language for that second Justification of which some speak, or for any increase of justification.”[4]

The Lutheran and early Protestant understanding that Christians remained at once sinner and saint, truly Simul justus et peccator, formed a vital role in Anglican churchmanship according to McIlvaine. He specifically rejected an over-realized union with Christ promoted by some Puritan divines and charged the rectors in his diocese to “strive to bring” a “spirit of self-abasement and renunciation before God” to the parishes they shepherded. McIlvaine found this imperative not in some gloomy Lutheran sermon, but in the Book of Common Prayer itself. He admonished his diocese to “study the language of our Liturgy” where they would find “the deeply penitential language of the communion-office. What confessions are there! what renunciations of all trust our own righteousness! what exclusive looking unto Jesus!” He urged his priests to “apply to the Articles” and to specially to read Article XI. We are, he declared, “accounted righteous before God only for the merit of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, by faith, and ‘not for our own works or deservings.’”[5]

The reclamation of Anglicanism’s commitment to the Protestant doctrine of justification is not merely historical or ornamental. It’s a vital part of applying consistently the approved documents the Province has chosen to base liturgical and theological unity on. The ACNA’s catechism states clearly that even those justified “fail to keep” God’s laws perfectly however hard they might try. God’s laws shows Christians their “inability to obey God’s Law” and their “need for God’s grace in Christ Jesus.” The Christian life, and more importantly the Protestant and Anglican life, is not one of preparing a meritorious life with which to offer God, but instead to live a life “marked by gratitude and joy…in gratitude for God’s grace in Jesus.” [6]

Notes

- Gerald Bray, Anglicanism: A Reformed Catholic Tradition (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2021), 2; Richard Snoddy ed., James Ussher and a Reformed Episcopal Church, viii-xii. ↑

- Charles P. McIlvaine, Justification by Faith: A Charge Delivered Before the Clergy of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Ohio (Columbus: Isaac N. Whiting, 1840), 17 ↑

- The first page of a quick (and admittedly unscientific) GoogleBooks search of the word “Sarum”before 1850 only pulled up the term in connotation with the territorial Bishop of Sarum in the Church of England ↑

- Peter Toon, endorsement of Thomas Garrett Isham, A Born Again Episcopalian: The Evangelical Witness of Charles P. Mcilvaine (Solid Ground Christian Books, 2011); William Carus ed., Memorials of the Right Reverend Charles Pettit McIlvaine (New York: Thomas Whitaker 1882), 8-11; McIlvaine, Justification, 26, 79. ↑

- McIlvaine, Justification, 62. ↑

- To Be a Christian: An Anglican Catechism (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2020), 111-113. ↑

'Charles McIlvaine and American Anglican Irenicism' have 3 comments

March 22, 2021 @ 7:01 pm John

Prof. Smith, four items.

First, not having read Bray’s book, I do not know what is meant by saying that contemporary Anglicanism is essentially a 19th century invention. Is this to say that Anglicans before the Oxford Movement (assuming this is the turning point) were essentially good Protestants, but the late tension between Anglicans and other Protestant bodies begins with the Tractarians insisting on the Apostolic character of the episcopate?

Second, you write as if questions relating to the sacraments, church order, etc have little bearing on the fundamental questions of soteriology. Whether 16th and 17th century Anglican theologians affirmed justification by faith and so were influenced by Luther is one thing, that they saw baptismal regeneration, the episcopacy, and the eucharist as somehow of secondary importance is a bold claim which you do not substantiate. That McIlvane departs from Hooker on justification is a rather awkward support for the claim 19th century Anglicans did depart from the 16th century legacy while inventing 21st century Anglicanism.

Third, you do not seem to be very familiar with the tendencies of the Oxford movement. The original Tractarians also did not seek “to perpetuate a distinct form of the British or Sarum rite, to preserve the episcopacy for its own sake, or a certain socio-cultural aesthetic.” The subsequent flowering of liturgical expressions by the Ritualists occurred only in light of the doctrinal work by Pusey, Newman, Keble, Froude, and until recently was only rarely realized the slum missions where Anglo-Catholicism truly took root. Regarding the doctrinal work of the Tractarians, it was focused on retrieving the doctrine of the Church as a supernatural body, not on retrieving a perverse neo-scholasticism. No less than McIlvane, they were interested in the “simplicity of the Gospel” would have heartily seconded him when it comes to looking exclusively to our Lord. They were not trying to reintroduce a doctrine of salvation by merit. But they understood the doctrine of justification, however important, is not the esse of the Gospel. Absolutized it reduces Christianity into an individualistic quest for salvation. Sorry for this generalization, but what the Tractarians attempted to recover was a robust understanding of God’s gift of himself to his renewed creation, the Church, the body of the redeemed joined to Christ by the Holy Spirit’s work through the Apostolic ministry, that is, they were trying to understand the Book of Acts.

Fourth, regarding your concluding statement, aside from your odd prioritizing of “Protestant and Anglican” over “Christian”, our liturgy, S. Paul, and pretty much the entirety of Christendom before the treasury of merit was invented in the late Medieval west, would say that to present one’s life as a fragrant offering to God and to be grateful for God’s grace in Jesus Christ were hardly activities in tension.

March 23, 2021 @ 11:05 am Will B

Amen to your third point, John. Neither Bray nor another similar thinker, Bp. Fitz Allison, in his work, understands Tractarianism as anything other than crypto-Romanism. Your description of the movement is superb and consistent with much of the Tracts themselves.

March 27, 2021 @ 8:22 pm Jonah+

John,

Thank you so much for saying this better than I could. As Will B said, I especially appreciate the clarity of your third point.