In his classic 1987 book Crisis and Leviathan, economic historian Robert Higgs convincingly argued that the vast growth in the size and scope of the American government over the course of the twentieth century was due primarily to government actions taken in response to national emergencies. Higgs identifies critical events such as the Great Depression, the World Wars, and the onset of the Cold War that had a ratchet effect on the exercise of government power, setting new precedents that constituted a new normal long after the crisis had abated. For this reason, the expansion of federal power in the American context is relatively easy to trace as cataclysmic events expose radical discontinuities in the historical narrative. Charting the growth of papal power in the Middle Ages is somewhat more challenging. It requires a different explanation than Higgs’ ratchet effect thesis as it was much more gradual, and at times imperceptible. Though one can identify critical flashpoints in the power struggle between the papacy and secular rulers that contributed to the expansion of papal power, these dramatic episodes should not necessarily be seen as definitive turning points in the narrative, after which everything had changed. This reality gives credence to the Roman Catholic claim that the papacy has always been considered the supreme authority in the church as the heir of St. Peter. However, an examination of the historical evidence demonstrates that the extension of papal power over western Christendom, while gradual, was aggressive and persistent and over time transformed the papacy into an oppressive institution that usurped the role of bishops in the ecclesiastical realm as well as the magistrate within the civil realm.

“Vicar of Christ”

Pope Innocent III, perhaps the most powerful pope in the history of the church, laid exclusive claim to the title “Vicar of Christ” as the basis for his power to remove bishops and kings from office. At his enthronement, it was said, “Take the tiara and know that thou art the father of princes and kings, the ruler of the world, the vicar on earth of our Saviour Jesus Christ, whose honor and glory shall endure throughout all eternity.”[1] The title itself was neither new nor foreign to those living in the Middle Ages. The novelty was in its exclusive application to the papacy. In the earliest centuries of the church, it had been used as a general description of the role of all bishops. After the Constantinian and Theodosian reforms of the fourth century, the Eastern church applied this term to the Christian prince. The Bishop of Rome, considered the first among equals among the provinces in the ancient church, throughout the early Middle Ages had held the title “vicar of St. Peter.” This term was meant to honor the Roman See due to its status as the capital of the empire as well as being the final resting place of the apostles Peter and Paul. The deference given to Rome then was not due to the officeholder governing the see, but due to the importance of the city in the early church. For example, in the Celtic church, whose own history preceded the mission of Augustine of Canterbury in 594, “the living pope was respected, but it was his great predecessor Peter, with the other saints and martyrs, who drew Celtic pilgrims to Rome.”[2] Even as Pope Gregory I asserted the primacy of Rome over all other bishops at the turn of the seventh century, Rome exercised no legal authority over the churches in the East or West. The papacy at this point did not collect tribute, serve as the court of last appeal, or impose its will in other jurisdictions through legates. The episcopate of the whole church was in practice superior to any individual pope. Thus, deference given to the Bishop of Rome did not preclude independent judgment exercised by bishops in other provinces, for they did not receive their ecclesiastical authority from Rome.

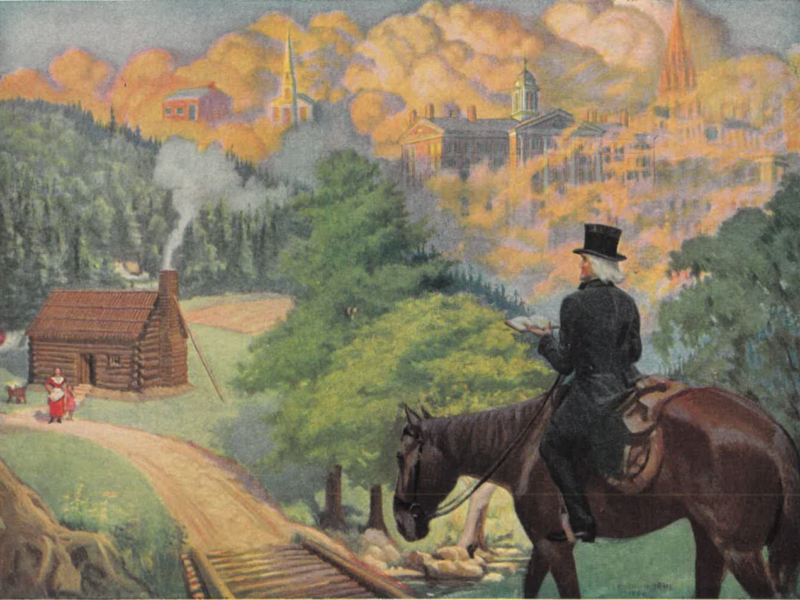

A Holy Roman Emperor

The first significant move made to enhance the political power of the papacy on the continent was the surprise coronation of Charlemagne as emperor in 800 A.D. by Pope Leo III. Though Charlemagne was by this ceremony recognized as the leading political authority in the West, the papacy gained even greater benefits by bestowing the crown, securing in return a guarantee of protection for the papal states against the Lombards as well as establishing itself, in theory, as the source of secular power. From this position of strength, the forged decretals of Pseudo-Isidore were penned in the mid-ninth century, further bolstering the increasingly bold claims the papacy would make in the later Middle Ages. The Donation of Constantine, from this collection of forgeries, was cited as the basis for papal authority over the entire church. In the short term, however, they had an adverse effect on the claims of the Bishop of Rome as Pope Leo IX’s attempt to use the Donation to claim primacy over the eastern patriarchs precipitated the Great Schism in 1054. While the split severely diminished Roman influence in the East, the departure of eastern patriarchs eliminated ecclesiastical rivals to Rome from the western church and opened the door for the papacy to assert its authority against the civil authorities.

Consolidation Through Reformation

Into this new vacuum came the reformer popes. Despite the overt power grabs by Leo III and forgeries of Pseudo-Isidore, it was the legitimate need for ecclesiastical reform in the eleventh century that proved to be the greatest impetus for the expansion of papal power. Hildebrand, a Cluny monk who served as the force behind five popes before becoming Pope Gregory VII in his own right in 1073, was crucial to initiating this process of consolidation through reformation. Gregory VII made lay investiture the battleground issue on which he would bring the current Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV, to heel. He insisted on the pope’s exclusive right to invest bishops with spiritual authority by bestowing them with the ring and staff. The goal was to eliminate secular political influence from ecclesiastical appointments. While this would not strike the modern reader as an unreasonable demand in pursuit of ridding the church of corruption and simony, it also represented a significant power grab for the papacy over against the state. The claims made by Gregory VII for papal supremacy over the state were not based on the divine grace received through ordination, but jurisdictional claims based on legal authority as head of the church as a corporation.[3] As it was, the clergy throughout the civil realm operated as a protected class, exempt from taxation and the enforcement of civil law, accountable only to the pope. This state of affairs had grown out of Emperor Constantine’s delegating to the church the right to hear and resolve cases involving ecclesiastical controversies in the fourth century, which had later extended to bishops presiding over even criminal cases that involved clergy by the seventh century.[4] By law, the church also enjoyed the privilege of collecting tithes without any accounting required to either king or people for how the money was used. Therefore, by claiming the sole right to invest bishops and clergy with spiritual authority, as Gregory VII did, the pope was in effect creating an elite class within civil society who owed their status to him alone and owed nothing to the civil authority within the realm in which they served. This was just and reasonable according to Gregory VII because, in his spiritual hierarchy, the lowest clergy ranked above the highest layperson in the civil realm; subdeacons prevailed over monarchs in all ecclesiastical matters. Reforming the church, for Gregory VII, meant properly reordering society such that ecclesiastical authority prevailed over secular authority. The lay investiture issue then was not merely about maintaining the purity of the church but asserting the dominance of the papacy over the state.

Henry IV at Canossa

Gregory’s main secular antagonist over the course of his tenure as pope was the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV. Tensions in this rivalry famously reached a climax at Canossa in 1077, where the recently excommunicated and deposed emperor intercepted the pope in the Apennine Mountain town and spent three winter days on his knees begging for absolution for his sins of intransigence against the pope on the investiture issue. Henry IV understood that papal excommunication would be the death knell of his reign as his lords would be freed from their oaths of loyalty to him. While later scholarship has called into question whether the events at Canossa represent state submission or the brilliant manipulation of the papacy by Henry IV, there is no doubt that throughout the Middle Ages, this amounted to an important public relations win for Gregory. At the end of the day, the prince was on his knees begging for forgiveness in order to have his kingdom restored, regardless of whatever additional political calculations were being factored in by the emperor.

The Norman Conquest

Gregory’s bold pronouncements laying claim to supreme legislative, executive, and judicial authority had staked out a considerable amount of legal ground, not all of which could be practically defended in his own day. Canossa served at least as a symbolic victory, but by 1085, Gregory would die in exile. The latter half of the eleventh and the early twelfth centuries proved to be quite eventful for church-state relations, especially in England. However, Charles Duggan argues in his essay on the growth of the papacy between the Norman Conquest to the death of King John, that the most important developments actually occurred below the radar. On the surface, both sides emerged from the various controversies managing to strike bargains that were in their favor.[5] The movement toward greater papal power was not in a straight line or in the same direction and cannot be traced to one defining moment of confrontation. For example, seven years prior to Gregory’s rise to the papal throne, William the Conqueror had invaded England with the blessing of pope Alexander II in the name of furthering reform of the English church. This is one of many episodes demonstrating that rather than being the source of peace and stability, spiritual reform for the papacy included the possibility of empowering kings to overthrow regimes not sufficiently toeing the line. However, the plan backfired for the papacy. Having established Norman dominance in England, William the Conqueror boldly resisted any further papal incursions into the country, issuing a decree in 1067 that the king of England had the right to determine whether the pope would be recognized in the kingdom. Another example can be found four decades later when, Anselm, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was permitted to receive his ring and staff from the pope in 1105 against the wishes of King Henry I, but only in exchange for the requirement that English bishops elected in the royal court pay homage to him as king. Similarly, the Concordat of Worms in 1122 brought an end to the investiture controversy in the Holy Roman Empire begun a half-century earlier by granting Emperor Henry V the right to be present at episcopal elections as well as the right to invest bishops and abbots with a scepter in exchange for his renunciation of the right to invest with the ring and staff. Thus, from these three examples it may be concluded that thirty-seven years after Gregory VII’s death, his vision for papal supremacy had been achieved, but not without considerable pushback from, and concessions to, civil rulers.

Canon Law in the Decretum of Gratian

The next major step in the expansion of papal power was taken with the publication of the Decretum of Gratian in 1140, which was a summary of the canon law. In one sense, Gratian’s work could be considered merely a codification of past ecclesiastical precedents, liturgical rites, and legal rules. However, its presentation as a body of church law, distinct from customary and civil law, led to a different way of thinking about canon law entirely. To this point in church history, canon law had been intertwined with the social and legal customs of the society in which it was observed. “There were ecclesiastical laws, a legal order within the church, but no system of ecclesiastical law, that is, no independent, integrated, developing body of ecclesiastical legal principles and procedures, clearly differentiated from liturgy and theology.”[6] In contrast, Gratian’s Decretum presented canon law as an external system of rules to be applied uniformly to every community. Moreover, this treatise was not only a summary and codification of precedents and conciliar canons, but an incorporation of new papal decretals. Smuggled under the umbrella of canon law were the positive dictates of recent popes, which were automatically assumed to be received as ancient law. Legal scholar Harold J. Berman insightfully concludes, “The system of canon law, as conceived by Gratian, rested on the premise that a body of law is not a dead corpse but a living corpus.”[7] This concept of a living corpus, always rhetorically preferable to the idea of “dead law,” was increasingly divorced from the cultures and peoples out of which it had initially arisen. Customary law by its very nature is slow to change and adapt, whereas dictates, papal or secular, imposed from the top down can quickly alter and modify the legal system without too many roadblocks. In the decades following the publication of the Decretum, summaries and glosses were produced and were in turn used as the basis for the issuance of further papal decretals that would then be added to the ever-growing body of canon law. Thus, Charles Duggan concludes, “For good or ill, the power of the medieval papacy at the peak of its prestige and influence was realized and made effective by canon law.”[8]

Henry II and Beckett

The dramatic interaction between the powers of church and state in the latter half of the twelfth century would provide an opportunity to put this new concept of canon law to test. In England, King Henry II attempted to restore law and order in his realm by curbing the privileges of the clergy, eliminating their right to exemption from civil prosecution for crimes with the Constitutions of Clarendon. Thomas Beckett, the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 to 1170, was assassinated in Canterbury Cathedral, ultimately, for his refusal to submit to the Constitutions. The king’s frustration with Beckett and his desire to be rid of the menace was interpreted by his guards as an order to execute the archbishop, an event that led to considerable political fallout for the king. Having been humbled and desirous of restoring his political reputation after Becket’s murder, Henry II agreed to the Compromise of Avranches in 1172 in which he promised to do penance and affirmed the right of legal appeal to the papal court in Rome. This right to send routine appeals to the Roman curia was a significant concession on the king’s part as it not only established the practice of appealing to Rome that increased rapidly in the following decades, but also carried the implication that Rome was the court of final appeal. On the surface, there weren’t any major political battles waged in the substance of these appeals. However, the war between ecclesiastical and civil authorities was being won by the papacy in the method of resolving legal disputes. Endless appeals to Rome led to the increased application of canon law within the various civil realms of Europe which would be the chief means by which papal authority would be extended in Europe. Civil authority would not be shaken by one deadly blow but would be eroded slowly as canon law began to create fractures and progressively chip away at the civil law of the realm. What had in ancient times had been a respectful deference toward Rome gradually became a legal obligation. Claims to papal supremacy and institutional unity would be built on the exchange of political benefits and favors in the flurry of litigation that inundated the papal court. In the words of Charles Duggan, what had been “a union of faith, love and loyalty became now a union of law, discipline and authority.”[9]

Growth of the Papal Court

The increase of routine traffic to Rome in the latter part of the twelfth century led to the massive expansion of the papal court. Roman bureaucracy grew to accommodate the inundation of appeals as the cost of such appeals compared to the potential political gain created an incentive structure in favor of seeking papal redress for even relatively small disputes. To navigate the Roman bureaucracy and ensure an appeal made its way to the relevant authorities, professional lawyers and lobbyists were needed to navigate the system. The sheer number of cases necessitated that the pope delegate his responsibility for hearing cases to his cardinals and chaplains, to whom the plenitude of power of his office was extended. According to the thirteenth cardinal, Hostiensis, cited by Charles Duggan, “the headship of the Church was, for practical purposes, not monarchic, but oligarchic.”[10] This new, elevated status for cardinals, whose decisions carried the same legal weight as the pope himself, attracted ambitious aspirants to the position. Likewise, civil governments sought to curry favor with the pope in the hopes of a red cardinal hat being awarded a politically expedient family member, one who could influence papal policy. Thus, the papacy was able to increase its control over the civil realm of Europe much more efficiently by offering carrots instead of wielding sticks, and providing seats at the Roman table instead of provoking outright confrontations with kings, which were fraught with risk.

Pope Innocent III, ruling the church at the turn of the thirteenth century, managed to consolidate more power to the office than any church official before him. From Innocent III came the boldest claims yet for the papal office, which would have been impossible to substantiate in any meaningful way even just a century earlier. As Jesus declared in the Great Commission that all power in heaven and on earth had been given to him, so Innocent believed that that power had been given to the Apostle Peter upon whom alone Jesus would build his church and to whom Jesus commissioned to feed his sheep. The head of the Roman See stood between God and man and had the power to rule the whole world in Christ’s stead. For Innocent, the priestly office was natural and created by God for good while the civil government was merely a product of man’s fallen human nature.[11] Civil rulers would from this point until the Reformation increasingly be thought of as a kind of necessary evil rather than having a sacred duty to serve as God’s deacon of justice.

King John and Magna Carta

One of the most famous confrontations that occurred between papal and civil authorities in the Middle Ages illustrating the increasingly arbitrary nature of papal rule was between Innocent III and King John. This episode is illustrative of the fact that the papacy was not a principled opponent of state authority but concerned itself only with ensuring that the heads of European states demonstrated political submission to the head of the church. Innocent III insisted that Stephen Langton be elected by the suffragan bishops as the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1206, which John opposed. Langton was exiled from the English realm and the ecclesiastical revenues of Canterbury were seized by the king. Unwilling to give ground on the right of investiture which the papacy now firmly held, the kingdom of England was placed under interdict in 1208 and King John was excommunicated the following year. Excommunication was a powerful tool in the papal arsenal that carried with it the threat of invasion from enemies without or a coup from enemies within. Kings deemed to be outside the church were no longer worthy of the obedience of their subjects and, therefore, foreign aggression and popular rebellion were encouraged by the papacy. Fearing an invasion from Philip Augustus of France, King John submitted to Innocent III and offered up his kingdom as a fief to the papacy, receiving it back only with a promise to render perpetual tribute. Stephen Langton was then permitted to return to England to serve as the Archbishop of Canterbury. However, circumstances had changed significantly in the time that he left. Any opposition by Langton to King John going forward would put him at odds with Innocent III, since the king of England was now a vassal of the pope. When the barons of England rose up against King John’s acts of tyranny and taxation with the Magna Carta in 1215, Langton supported them. King John was no more a virtuous ruler in 1215 than he had been in 1209 when he was excommunicated. The only difference was that he was now in a position to do the pope’s bidding. Therefore, Innocent III called for the invalidation of Magna Carta and opposed the barons’ attempt to restrain the monarchy.

The Excommunicated Emperor

The trend of strong lawyer-popes continued with Gregory IX, a nephew of Innocent III who ascended to the papal throne in 1227. Despite the fact he was advanced in years, he was an energetic pope and ambitious for consolidating the power that had been gained for the church at the height of its power under Innocent. Gregory strengthened the papal inquisition against heresy, called for the Sixth Crusade in the Middle East, and excommunicated the Holy Roman emperor, Frederick II, for his delay in performing his promise to recover Jerusalem. Frederick II protested against the bold pronouncements of Gregory IX for the church saying, “She who calls herself my mother treats me like a stepmother.”[12] Yet off to the Holy Land he went and proved remarkably successful in reversing the western losses of the Fifth Crusade. Upon his return, he was excommunicated again. In the words of Philip Schaff, “he was excommunicated for not going, he was excommunicated for going, and he was excommunicated on coming back, though it was not in disgrace but in triumph.”[13] A year later, when Frederick II issued the Constitutions of Melfi for the Kingdom of Sicily, Gregory IX protested the temporal ruler making temporal laws in the temporal realm. While Innocent III had backed King John against the nobility in his realm, Gregory IX now supported the nobility in Sicily when Frederick II was perceived as a threat to his power. At the same time, Gregory ordered his canonist, Raymond Penyafort to begin a new compilation of papal decretals that would replace Gratian’s Decretum as the primary canon law text in the west upon its publication in 1234, further enlarging the body of canon law.

“Two Swords”

By the beginning of the fourteenth century, Pope Boniface VIII began to dogmatically articulate the implications of the “two swords” doctrine. In his 1302 encyclical, Unam Sanctam, Boniface argued that the spiritual unity of the one body of Christ demanded one head of the church who was responsible for wielding all earthly power. The two swords Jesus referred to in Luke 22:38 represented spiritual and temporal power. Of these two, “the former is to be administered for the Church but the latter by the Church; the former in the hands of the priest; the latter by the hands of kings and soldiers, but at the will and sufferance of the priest.”[14] According to this doctrine, the church received its sword directly from Christ while the state’s authority was obtained only indirectly from God through the intermediary of the church. The papacy, as the highest spiritual power on earth, could only be judged by God, for, citing Jeremiah 1, God gave his prophet authority over nations and kingdoms. Therefore, the civil realm was considered inferior and beholden to the supreme ecclesiastical authority. It did not exist as a good or legitimate power in its own right. The goodness and godliness of the civil ruler was determined by his usefulness and loyalty to the pope.

“Babylonian Captivity”

Despite Boniface beginning the 14th century with bold claims for the papacy, the next hundred years would be considered the most disgraceful for the institution as corruption and political infighting prevailed. Beginning in 1309, the papacy was relocated from Rome to Avignon, France where it would remain for the next seven decades. This era came to be known as the Babylonian Captivity of the papacy as the pope was closely tied to the French monarchy and lacked the political independence that he had enjoyed in Rome. For many, the Avignon papacy represents a pendulum swing back towards state power over the church that occurred in reaction to the growing power of the pope from the eleventh century onward. The very name “captivity” implies that the papacy was taken hostage and weakened by its time in Avignon. On the contrary, the so-called Captivity is better understood as within the trend toward greater papal power. The Captivity began with the election of Clement V, a Frenchman, to the papacy who decided to remain in Avignon instead of traveling to Rome. “If the Avignon popes were undoubtedly weaker than Innocent III at a purely political level, the papacy and the papal curia in terms of ecclesiastical government and administration were stronger and more highly organized than they had ever been before.”[15] Far from minimizing the church’s influence in the world, the time in Avignon strengthened the papacy by providing the pope with what had been desired since the crowing of Charlemagne in 800: political protection from one of Europe’s most powerful monarchs. This protection and patronage allowed the papal curia to focus its attention on administration as legal traffic reached a climax for the Middle Ages. Yet this influence came with a significant cost. The moral authority of the papacy is what had led to such extensive political influence. Now the political power seemed to undermine the pope’s moral authority as he was increasingly seen as the chief administrator rather than as a spiritual leader.

War of the Popes

In 1377, Pope Gregory XI finally decided to break away from French monarchical influence and return the papacy to Rome, only to pass away soon thereafter. The people of Rome clamored for a Roman pope to replace Gregory XI desirous of retaining the papal government there and not losing it once again to Avignon. Under pressure from the Roman mob, the cardinals in conclave selected the Italian Urban VI, a man with a waspish disposition who did everything in his power to alienate the foreign cardinals within the college. In August 1378, a majority of the College of Cardinals met in Anagni to declare Urban’s election null and void and select a new French military man as pope in his stead. So far removed from a position dedicated to the shepherding of Christ’s sheep, the papal crown was recognized as a symbol of political power over which not only individuals fought to obtain, but a chess piece for which national factions throughout Europe vied for national supremacy. The English and the Holy Roman Empire tended to support the Roman popes with France supporting the Avignon popes, neither willing to give ground.

The papacy had reached a position of dominance over secular kingdoms. The next major challenge would be to fend off ecclesiastical challenges from councils. From 1378 to 1415, papal authority suffered a steep decline in prestige as the church was divided between rival claimants to the throne of St. Peter and the title of “vicar of Christ.” The mask of papal absolutism was slipping away, and the institution was being revealed for the political trump card that it was. Laid bare, the papacy was nothing more than another monarch vying for supremacy in Europe. To restore some sense of legitimacy, it was important for councils to be called in order to reach a compromise that would reunite the church. A council was called in Pisa in 1409, wherein a third pope was elected with the current popes refusing to relinquish their titles, exacerbating the ecclesiastical chaos still further. Five years later, the Council of Constance was called, attempting once again to find a resolution to the schism. The Council proved to be a success upon the election of Martin V and the resignation of the preceding claimants.

Conciliar Authority

With two major Councils within the span of five years, serious questions were raised about the exact nature of the papal hierarchy: was the pope supreme over councils or were the councils, by virtue of the fact that they had produced a peaceful settlement and elected the next pope, supreme over the papacy? As obvious as the latter would seem based on the historical reality, Martin V would allow no such theory to stand. In the words of Philip Schaff, “Martin and his successors feared councils, and it was their policy to prevent, if possible, their assembling, by all sorts of excuses and delays. Why should the pope place himself in a position to hear instructions and receive commands?”[16] Though owing his title to the council, he nonetheless denied conciliar supremacy in favor of papal absolutism. Subsequent popes over the course of the next century repeated the pattern of making a show of submitting to councils while in conclave only then to assert their supremacy over councils after their election.

The Renaissance popes of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries are well known for their corruption and avarice. This period is considered by both Protestants and Roman Catholics alike to be a nadir in the history of the church. However, this extensive corruption must not be understood as a unique abuse or exception to the history of the papacy, but rather as the culmination of the growth in unprecedented power that had been accumulated by the church over against the state and councils throughout the high Middle Ages. Gregory VII’s claims in the eleventh century had been achieved, but the reforms upon which such claims were justified were not.

Ripe for Reformation

It is for good reason that Giovanni de Medici upon his ascension to the papal throne in 1510 as Leo X could say, “God has given us the papacy, now let us enjoy it.” By the sixteenth century, the issue was not simply that the pope had a disproportionate amount of power in the church or within western Christendom as a whole, but rather that it had a corrupting influence on the practice of real Christianity. The core issue of Martin Luther’s Ninety-five Theses was the corruption of the doctrine of repentance in the church, which Leo X had monetized to raise funds for St. Peter’s Basilica. Beyond its ability to dominate other ecclesiastical councils and authorities and claim political supremacy over civil rulers, the papacy had begun to assert its authority to tyrannize the conscience. In response, the Protestant Reformation would be launched, first to reform the theological corruption in the church and then to reform the civil and ecclesiastical polities as well.

Notes

- Philip Schaff and David S. Schaff, History of the Christian Church Volume V: The Middle Ages from Gregory VII to Boniface VIII, 1049-1294, (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994) 155. ↑

- Kathleen Hughes, “The Celtic Church and the Papacy” in The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages, ed. C.H. Lawrence (London: Burns & Oates, 1965), 23. ↑

- Harold J. Berman, Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1983), 207. ↑

- Philip Schaff and David S. Schaff, History of the Christian Church Volume III: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity, 311-590, (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994) 103. ↑

- Charles Duggan. “From the Conquest to the Death of John,” in The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages, ed. C.H. Lawrence (London: Burns & Oates, 1965), 68. ↑

- Berman, 202. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Duggan. “From the Conquest to the Death of John,” in The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages, 72. ↑

- Duggan, “From the Conquest to the Death of John,” in The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages, 115. ↑

- Ibid, 122. ↑

- Philip Schaff and David S. Schaff, History of the Christian Church Volume V: The Middle Ages from Gregory VII, 1049, to Boniface VIII, 1294, 159. ↑

- Ibid, 185. ↑

- Ibid, 186. ↑

- Boniface VIII, Unam Sanctam https://www.papalencyclicals.net/bon08/b8unam.htm ↑

- W.A. Panton. “The Fourteenth Century,” in The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages, 159. ↑

- Philip Schaff and David S. Schaff, History of the Christian Church Volume V: The Middle Ages from Boniface VIII to the Protestant Reformation, 1294-1517, (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994) 168. ↑

'Canon Law and the Ecclesiastical Leviathan' has 1 comment

February 9, 2023 @ 12:59 pm Paula W Heyes

An excellent and well-researched analysis. I will point out that the idea of apostolic succession was defined, if not promoted, by Ireneaus, long before there was any question of using it as a political tool; however, he also defined it not just in terms of laying on of hands, but of holding to apostolic doctrine..