The Common Service: The English Liturgy of the Church of the Augsburg Confession. By James D. Heiser. Malone, TX: Repristination Press, 2022. 323 pp. $39.99 (hardcover).

Acknowledging that liturgical study is not the favorite subject of everyone, why would an Anglican read this book? Why should an Anglican care about the Lutheran liturgy? The answer is found in the XXIVth Article of the Augsburg Confession: “Falsely are our churches accused of abolishing the Mass, for the Mass is retained by us and celebrated with the highest reverence.” The Book of Common Prayer and the Lutheran Divine Service have the same ethos, conservative revision of the Roman Mass, and have had significant historical correspondence with each other. To learn something of one is to better understand the other.

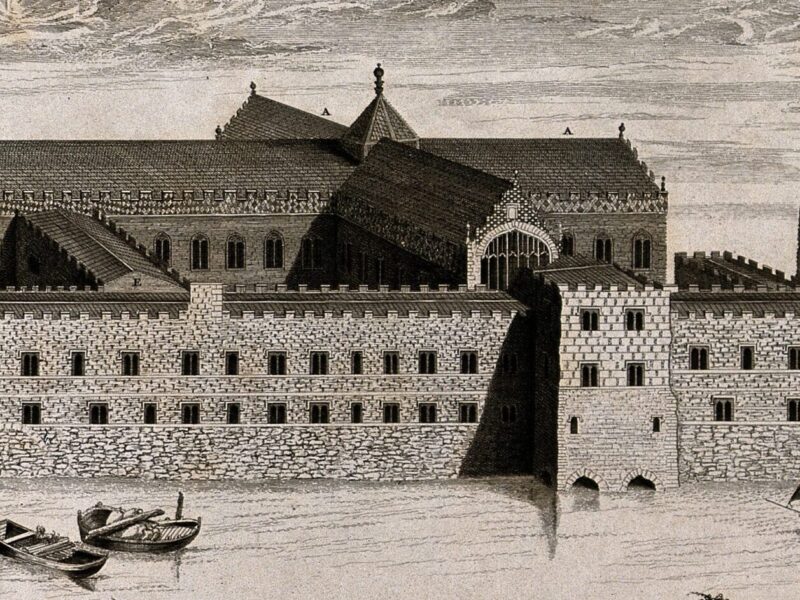

Bp. Heiser has organized his book into three major sections: The Rise of the Common Service, The Age of the Common Service, and The Decline of the Common Service. The first section recites the history of Lutheran liturgy in North America. This initially took the form of the mother tongues of the immigrants who practiced Lutheranism. But as they acclimated to the new world and had children who were citizens of the new country, it was realized that the liturgy needed to be available in English. To this end, the German and other church orders must be translated, but not slip-shod, rather with great care and consideration.

As this need was realized some apologetic was made for the project. Heiser quotes a text which he terms “the four uses and advantages” of a good liturgy. To summarize:

1. A good liturgy…affords ministers, and especially those who are just entering on the sacred office, an exemplar, in multiplied forms, of the manner in which devotional feeling and the sense of dependence and want, should be expressed on public occasions.

2. Public prayer is designed to lead the minds and hearts of many in the exercise of devotion. The minister in the sacred desk does not pray in his individual capacity, but as the representative of his flock…

3. A good liturgy should embody, and clearly exhibit, the great doctrines and duties of our holy religion.

4. Lastly, the use of a common liturgy, of common forms, brings uniformity into the public worship of the many congregations connected with any particular church. (41–42, selected)

A good liturgy suggests that there may also be bad liturgy. Heiser is not shy to offer his own commentary and critiques throughout the book as to the relative quality of the various forms the liturgy took. This is one of the most desirable and enjoyable aspects of reading his book.

Having identified what a good liturgy is, the next logical step is to evaluate the texts at hand and make some judgments. There was not a single German rite, but a number of regional variants. And so, the committee that worked on the “Common Service” worked under a rule. The Rule was: “the rule that shall decide all questions arising in its preparation shall be: The common consent of the pure Lutheran Liturgies of the sixteenth century, and when there is not an entire agreement among them, the consent of the largest number of those of the greatest weight” (76). Progressing through this process a service book was drafted, but it was not simply a majority text project—it also incorporated some new elements that had come into common usage in the American church. Heiser includes the pertinent information as to what German liturgies were considered to have the “greatest weight” and also the fact that the verbiage for various parts of the service was often borrowed from the Book of Common Prayer. Some brief citation of how the Lutheran liturgies impacted the creation of the first Edwardian prayer book is also included.

Finally, in 1891, the “Common Service” was finished and submitted to the synods for adoption. As Heiser begins to discuss the adoption of or struggle against the new liturgy, he includes a couple of enlightening sentences as to his own ethos: “Nothing gives greater power to a denomination than a common worship. It lets people know who and what you are” (119). (It should be noted that Bp. Heiser’s own synod is in the midst of preparing their own service book, missal, and hymnal upon these principles. Thus the book under review serves as an apologetic for the project.)

The German tradition was not the only Lutheran tradition. In fact, it may not even be the most important. Heiser thus spends some time and ink discussing and analyzing the impact of the “Common Service” on the Norwegian synods. The difficulty here is that the Norwegian musical settings were generally different from the German. The text itself was acceptable, but the Norwegian books did introduce a few deviations from the 1891 “Common Service.” Some of the Norwegian service books printed the “Common Service” as a second rite.

This leads to the question of whether changing a word or a prayer here or there is changing the service. Heiser is familiar with Dix’s arguments for the shape of the liturgy and makes some comments on a Lutheran shape. Obviously, in the strictest sense, any change is changing the service, but does it betray a new ethos? This is really the crux of the argument in the third section of the book. This portion of the book will carry the reader into the modern era.

Whereas the “Common Service” was in some ways a unity effort, 20th-century Lutheranism descended into division. Along with this division came “liturgical chaos.” Heiser quotes an author named Graebner who identified this condition in the 1930s. Heading into the 1950s, the Lutheran world began to look outward for liturgical ideas. The desire for ecumenism across disparate particular churches led to changes in the lectionary and liturgy. Eventually, this led to the multiplication of liturgies. Now, if you pick up a Lutheran hymnal crafted since the 1970s, there is not a singular “Common Service” but a plethora of Divine Service settings and options to tailor the worship of the church to individual taste and localized custom.

Bp. Heiser is insightful throughout the book. What’s more, he is generally right. The multiplication of rites has undermined common prayer and served to weaken the worship and teaching of the church(es). Anyone with even a faint knowledge of contemporary Anglicanism could recognize that our churches are in a similar plight. So, though Heiser’s book is Lutheran-specific, there are many principles and insights that can be extrapolated into an Anglican context. That it is well written is a bonus that is not always a feature of such studies. Read it and learn.