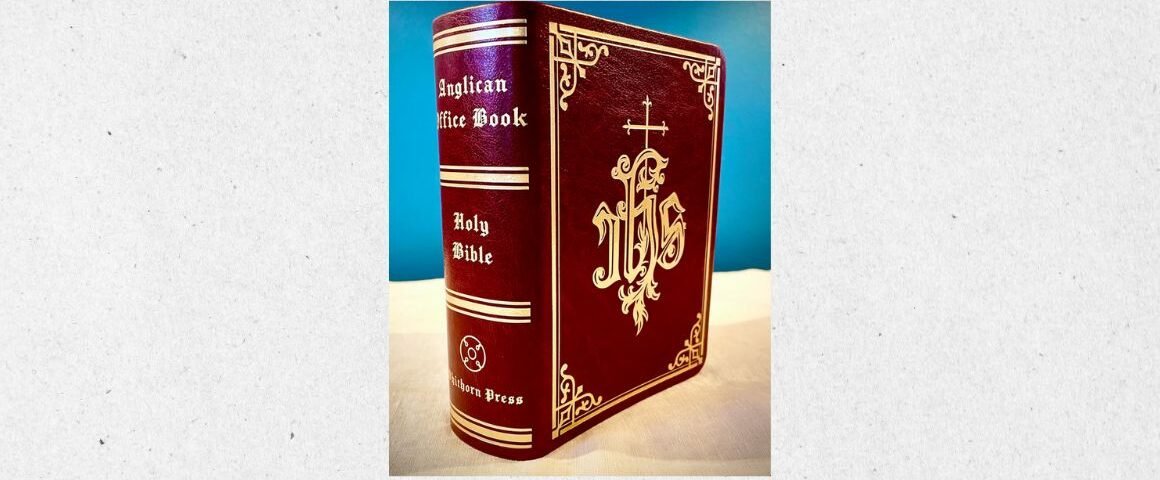

The Anglican Office Book, 2nd Edition. Edited by Charles Lance Davis. Lake Almanor, CA: Whithorn Press, 2023. 2,247 pp. $125 (leatherette).

The first edition of The Anglican Office Book was published in 2021, with the purpose of presenting “the entire Divine Office, through the prism of the classical Prayer Book tradition, in a format designed to be accessible by parishes, laymen, and clerics alike.” More precisely, it is “largely a synthesis of Fr. [Paul] Hartzell’s 1944 and 1963 editions” of a book published by Hartzell titled The Prayer Book Office. As such, it is “a renewal of Fr. Hartzell’s, and indeed the whole of traditional Anglo-Catholicism’s, vision for an English liturgy embodying the best of classical Anglicanism with the rich heritage of the Mediæval Church” (I). This second edition is meant to address “certain shortcomings in that first edition that left a feeling of incompleteness to the work.” The most noticeable change is that the second edition includes the KJV Bible, as well as “an expanded offering of feasts and festal propers, clarification of rubrics, and an additional two-week Psalter scheme.”[1] In his preface to the second edition, the editor, Charles Lance Davis, expresses his hope that “this new edition of The Anglican Office Book will serve not only to increase the number of the clergy who pray Mattins and Evensong, but also that more of the laity will likewise join their voices with the Church in her unceasing praise of God in earth as in heaven” (II).

As a physical book the AOB is a work of masterful craftsmanship, with leatherette binding, gilded page edges, and ten bookmark ribbons. It lies flat easily even from the first use, a valuable feature given that the book is fairly dense. The pages are thin (presumably in order to reduce the book’s size), so care should be taken to avoid tearing them. This is a worthwhile payoff, though, as the second edition is compact enough to make it an easily portable travel companion, even with the addition of the KJV. Overall, these elements come together to form a suitably elegant physical complement to the rich spiritual content within.

Turning to the book’s contents themselves, the fact that the AOB is designed to be an Anglican office book informs both what it includes and what it leaves out. On the one hand, it contains offices for the Little Hours—Prime, Terce, Sext, None, and Compline—to supplement Mattins and Evensong, as well as a number of Occasional Prayers and offices not found in the 1928 BCP, which is the Prayer Book that serves as the AOB’s basic foundation. On the other hand, it does not include liturgies for Holy Communion, Confirmation, or Baptism, among other services. From these omissions it should be apparent that the purpose of the AOB is not to be a standard Book of Common Prayer that encompasses the entire life of the church, but to serve a specialized role in allowing for “a fuller cycle of prayer than the two Cranmerian offices [of Mattins and Evensong] afford.” The AOB fulfills this role commendably, providing “a richer experience of the daily cycle of prayer and psalmody” via the Little Hours for those who desire it, yet never promoting them at the expense of the standard Prayer Book Daily Office. Indeed, the general rubric for the Little Hours states that they are “supplementary offices, and in no instance should replace the principal hours of Mattins and Evensong” (xvi). This is a salutary reminder, as we can be tempted to treat those who observe the Little Hours as further along the path of holiness than those who only recite the BCP Daily Office. They are a welcome option, but as the AOB itself makes clear, declining to observe them is by no means a spiritual shortcoming.

Another major distinctive of the AOB—namely its expanded Kalendar of feast days and memorials relative to the 1928 BCP—deserves consideration. The AOB is, by its editor’s own description, part of the mid-twentieth-century heritage of “Anglo-Catholic devotional practice” (I). Consequently, numerous parts of the AOB invoke the Blessed Virgin Mary and other saints in the manner of “ora pro nobis.” However, in many of the collects for the aforementioned feasts and memorials there is invocation of an indirect sort, where, rather than directly addressing the saint, one prays to God for the saint’s intervention. For example, the collect for the feast day of St. Augustine of Hippo reads as follows:

O GOD, who didst give blessed Augustine as a Catholic Teacher unto thy Church, to the expounding of the mysteries of Holy Scripture: grant that we may ever be enlightened by his teaching, and upholden by his prayers. Through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. (545)

Other collects similarly petition God for the saints’ help, merits, and intercession. Whether such indirect invocation qualifies as the sort of invocation rejected by Article XXII is debatable. Herbert Thorndike argues in favor of this sort of invocation, where prayers “are made to God, but to desire His blessings by and through the merits and intercession of His saints”:

[This] kind [of prayer to the saints] seems to me utterly agreeable with Christianity, importing only the exercise of that Communion which all members of God’s Church hold with all members of it, ordained by God, for the means to obtain for one another the grace which the obedience of Our Lord Jesus Christ hath purchased for us without difference, whether dead or alive; because we stand assured that they have the same affection for us, dead or alive, so far as they know us and our estate, and are obliged to desire and esteem their prayers for us, as for all the members of Christ’s mystical Body. Neither is it in reason conceivable that all Christians from the beginning should make them the occasion of their devotions as I said, out of any consideration but this. For, as concerning the term of ‘merit’ perpetually frequented in these prayers, it hath been always maintained by those of the Reformation that it is not used by the Latin Fathers in any other sense than that which they allow. Therefore the Canon of the Mass and probably other prayers which are still in use, being more ancient than the greatest part of the Latin Fathers, there is no reason to make any difficulty of admitting it in that sense.[2]

Notably, Thorndike also observes that while prayer to the saints in the manner of “ora pro nobis” is not idolatry, nonetheless “the consequence and production of it not being distinguishable from idolatry, the Church must needs stand obliged to give it those bounds that may prevent such mischief as that which shall make it no Church.”[3] For Thorndike, then, there is a significant difference between direct invocation and indirect invocation, with the latter being uncontroversial in his view. My object in mentioning this is not to state definitively whether Thorndike’s acceptance of indirect invocation is right or wrong, but to illustrate that such prayers as these in the AOB fall under more of a gray area than the direct approach typified by the formula “ora pro nobis.” That said, if conscience compels one to omit any and all invocation of the saints, even the indirect sort, those who are considering buying this book should be aware that no one is obligated to use all of the material contained therein, nor is doing so necessary to derive spiritual benefit from it. Bishop Sutton of the Reformed Episcopal Church says as much in his foreword to the AOB:

By my commending The Anglican Office Book as a “resource,” I am not endorsing everything in it to constrain schedules and convictions. The work contains a full regimen of daily prayers that some will not be able to keep due to time or other commitments. Since the book comes out of the larger Anglican world, there are additional feast days, hymns, and prayers to saints such as the Blessed St. Mary. Some, out of concern for fidelity to the formularies of their particular Churches, may by conviction of conscience be unable to adopt all of these prayers as their own. Others—emphasizing equally historic formularies and interpretations thereof—understand prayer requests of the great “cloud of witnesses” by which we “are compassed about” (Hebrews 12:1) to be advantageous to Christian devotion. Use what you may in this resource according to life’s demands and personal conviction. Leave out what either limit. (IV)

Whether it is worthwhile to buy an office book that one knows in advance will require a certain amount of omission to maintain a clear conscience is a decision people have to make for themselves. For my part, I can say the Anglican Office Book is wonderful to have because it combines the 1928 Daily Offices, the Little Hours, an optional lectionary (1549) that follows the calendar year rather than the liturgical year, and the KJV Bible, on top of many Occasional Prayers, offices, and hymns not found in American or English Prayer Books, all bound together. Having all of these elements in one book, and a book that inspires reverence by its own physical splendor, is a blessing for which the editor deserves thanks. His time and labor spent in further refining and improving on what was doubtless already an arduous undertaking is much appreciated.

Notes

- A “fairly complete list of significant alterations made to the 2nd edition of the AOB,” according to the editor, reads as follows:-Entirely new layout and typesetting-Several feasts have been given additional propers (i.e. hymns and antiphons) so as to prevent overuse of the Commons material-Additional two-week Psalter that provides variable psalms at the Little Hours (a la Pius X)-Psalm 14’s verses that were omitted from the 1928 psalter have been restored

-The Meal Prayers are given in Latin and English (derived from the Sarum form)

-The full Preces are now given at Mattins, and the option to pray “God save the King” is restored

-St. Charles the Martyr has been upgraded to Double 2nd and given a complete office derived from the office he once enjoyed in the 1662 BCP

-Numerous rubrical clarifications to ease in the saying of the hours

-No longer do any lines in the psalms begin with the verse-division asterisk—this should make them easier to sing unpointed

-Full propers are included for those Sundays which vary between 1662/1928/1962. Anybody following the English or Canadian BCPs can now fully conform the AOB office to their local usages.

-Invention of the Cross (May 3) has been given a full proper office

-The OT breviary canticles have been included

-“Holy” has been restored to the Nicene Creed (in brackets for those places that require strict BCP conformity)

-The Alma Chorus Domini hymn from Sarum has been added at Compline on Whitsun and Sweetest Name

-All feasts with proper psalms and lessons are now indicated as such in the proper of the season/saints

-There’s three times as much art in this edition compared to the first

-Our Lady of Walsingham, St. Charles the Martyr, and the feast of the Most Precious Blood have been given proper psalms and lessons

-Most significantly, the Bible is included. The book is arranged as follows: Old Testament, AOB, New Testament, Apocrypha (thank you, Michael Mattson, for this suggestion!)

-Memorials added:

Aelred, March 3, Abt. C.

Simon Stock, C – May 16

Brendan – Abt. C. May 16

Aldhelm – B.C. – May 25

First BCP 1549 – June 9

Isaac the Syrian – June 18

Translation of St. Benedict – July 11

St. Mary of the Snows – August 5

John Mason Neale – August 7

Raising of St. Lazarus – Sept 2

Evurtius – Sept 7

Holy Name of Mary – Sept 12 ↑

- Herbert Thorndike, An Epilogue to the Tragedy of the Church of England, Book III (“The Laws of the Church”), in Paul Elmer More and Frank Leslie cross, eds., Anglicanism (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 2008), 350. ↑

- Thorndike, Anglicanism, 352, italics original. ↑

'Book Review: “The Anglican Office Book, 2nd Edition”' has 1 comment

September 1, 2023 @ 12:19 pm David Chew

A very gracious review. Lance has labored to produce a tool useful to the spiritual lives of, not only Anglicans, but all Christians (including this Presbyterian). I believe this will continue to be sought after for the next century, at least, as a basis for spiritual growth in prayer, taking a prominent place among the other notable prayer books, breviaries, and helps of the past.