This essay was written for and previously submitted to Cranmer Theological House seminary.

***

In his response to Sinclair Ferguson’s essay on sanctification, “The Reformed View,” Lutheran theologian Gerhard O. Forde makes an astute distinction between the ability to well define sanctification and to well practice it. Says Forde, “The description may be quite true, nice, accurate, or even enticing, but it may be accompanied with an inadequate understanding of how to effect such things evangelically. We can end by preaching a description of the sanctified life but doing little or nothing to bring it about” (emphasis mine).[1] It is just here, in going beyond the difficult task of description to the even more difficult task of “bringing it about,” that Anglican spirituality shines brilliantly, illuminating not only the map that describes the path but casting light onto the path itself.

The Christian life is challenging. The follower of Jesus is at war internally with “the law of sin which is in [his] members”[2] and battling externally with an enemy which tirelessly “walketh about, seeking whom he may devour.”[3] He is perpetually up against forces which St. Paul calls “principalities,” “powers,” “rulers of the darkness of this world,” and “spiritual wickedness in high places”[4] – a description of not only the way in which this world is governed and ordered, but, chillingly, a revelation that despite our embodied existence, these forces are ghostly and intangible. How are we to do battle with an enemy we cannot see? That we cannot touch? How does the lion-stalked follower of Jesus avoid becoming a meal? How does the hungry Christian avoid becoming a glutton? What have the creeds and doctrines and dogmas of the Church to do with all of it? In a world built according to demonic design principles and governed in a like manner, how can the Christian “study to be quiet…and to work with your own hands”[5] and “with quietness…work, and eat their own bread,”[6] exhortations that are given in the name of – and therefore in accordance with the principles and governance of – the Lord Jesus Christ?

How are we to live and grow as Christians in this world? How do Anglicans progress in sanctification against the soul-deforming pressures within and without?

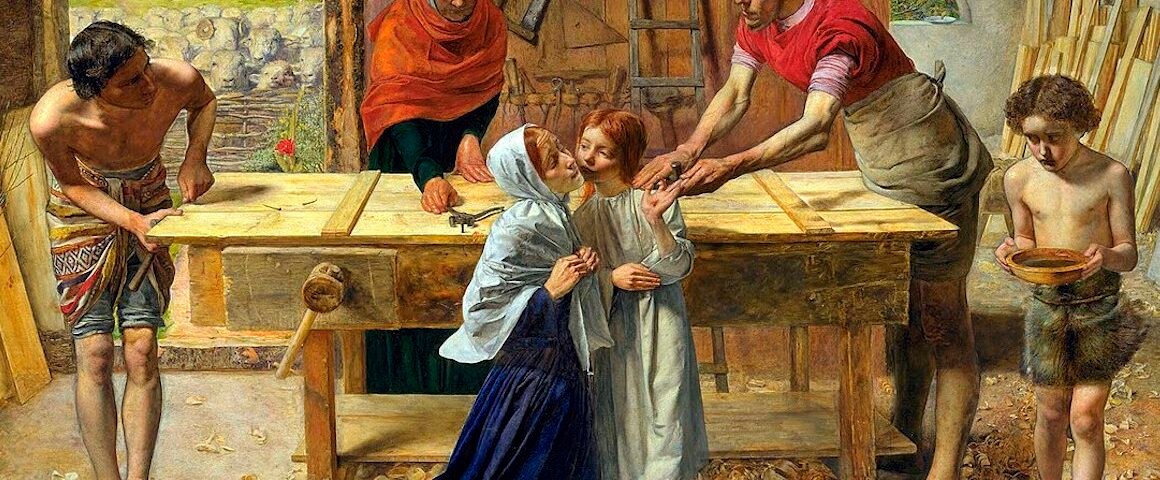

This essay will attempt to look at the work of Christian discipleship in the Anglican tradition of spiritual formation through the lens of apprenticeship to the carpenter king. It will take a specific look at the Benedictine arrangement of the Anglican ascetical schema as the way in which Anglicanism succeeds, by providing a form of apprenticeship. We will first look at the monastic project in its Benedictine expression as a basis for growth in sanctification; then we will look at the parish as the inheritor of the spiritual riches mined during the Benedictine monastic experiment, during which we will examine the tools and methods Anglicanism gives for instruction and practice of the Christian life.

Apprenticeship is a helpful way of conceptualizing growth in the Christian life. To live as a Christian is to enter a trade, complete with particular work toward which all efforts are directed; a living tradition of craft rich with its own lore, forms, and liturgies, all of which are governed by ideals towards which the worker and his work strive; specialized nomenclature dense with meaning; and tools designed for accomplishing the work. It must be learned by the body as much as by the mind, and learning can only happen if there are competent journeymen, under the rule and direction of a master, who can instruct the apprentices in an environment that philosopher Richard Sennett calls a “workshop.”[7] As one poet put it, the journeyman “[does] it right/so I [can] see. . .[he] wears a silver bracelet/that shines like a lamp/and underneath is the hand I read.”[8] The body of the journeyman or master craftsman is both the text that the apprentice reads and the light by which they read it. The material conditions in the workshop are such that there is an economy of motion and availability of materials conducive to the accomplishment of the work. Situationally, there may be secrets to successful execution of the work shared by the more to the less experienced, wise insights given that enlighten the greenhorn and expand their imagination for what is possible. In time, the craft sinks into the apprentice – they no longer practice the trade as though it were exterior to them, as though they were striving toward an ideal; the ideal becomes enshrined in the temple of their body and their every movement enacts it.

The Benedictine Project

There was perhaps no greater influence on English Christianity than St. Benedict. His Rule framed in the religious culture of the British Isles, as it was not only the guide for his own communities, but a touchpoint for many other Western monastic traditions that likewise had a presence in England, Wales, and Scotland. At the time of the Reformation, north of 800 monasteries existed on the island, and if one were to take a time machine back to that era and wander about, one might question whether they were in a reputable village or town without brothers present to center the local activities around the tolling of their bell. From the time that St. Augustine of Canterbury brought Benedictinism to England in AD 597 – a shift which brought the pre-existing Celtic monastic communities into alignment with the Rome-sent Benedictine communities – until the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s, the Benedictines were the primary liturgical, ascetical, and theological educational influence in England. It was in this religious ecosystem, saturated as it was by monastic presence, that the imagination of what it meant to be a Christian on English soil took shape. It is helpful, then, to try and understand what St. Benedict and his communities taught about growth in the Christian life so that his thought can be noticed in the Anglican Way of following Jesus.

Before discussing the specifics of Benedictine spirituality, it is worth noting what St. Benedict claimed was his aim and determining whether this is consonant with Scripture. In the Prologue to his Rule, St. Benedict predicates what follows on one being “ready to give up your own will, once and for all, and armed with the strong and noble weapons of obedience to do battle for the true King, Christ the Lord.”[9] One can hear in this Paul’s teaching that we have been “translated…into the kingdom of his dear Son”[10] and his exhortation to the Roman Christians that they not “yield…[their] members as instruments of unrighteousness unto sin: but yield yourselves unto God…and your members as instruments of righteousness unto God.”[11] The Christian life is a war, and those that are citizens in the kingdom have the honor of doing battle with their bodies for that kingdom’s King, Christ the Lord. St. Benedict invokes Romans 13:11 to tell the would-be monk that they must awaken and rise up; Psalms 34:12 and 95:8 and Revelation 2:7 are used to emphasize the Rule’s very first word, “listen”; he points to Isaiah and David and Paul to say that we must be clothed “with faith and the performance of good works”[12] and, having asked the Lord which good works, to actually listen and then perform them; importantly, the people who accomplish good deeds “judge it is the Lord’s power, not their own, that brings about the good in them” as both David in the Psalms and Paul in his letters to the Corinthians attests; and, indeed, Our Lord Himself encourages good works in Matthew’s Gospel when he compares those who hear His words and does them to the wise man that built his house on the rock.[13] That these do not come to us naturally and must be accomplished by God’s grace is acknowledged by Benedict. Nevertheless, following Benedict’s monastic forbears, he makes our participation with His grace an explicit assumption.

Since we belong to the Kingdom of Jesus, since He speaks to us, since we must become sensitive to hear His voice, since we must obey – all enabled by the Lord supplying us “the help of His grace”[14] – St. Benedict thinks of himself as establishing “a school for the Lord’s service”[15] to ripen the faculties and teach the methods conducive to these tasks. As he concludes his Prologue, Benedict’s words to his would-be monks are among the most tender and pastoral in the broad corpus of Christian literature. It is quoted here at length:

Do not be daunted immediately by fear and run away from the road that leads to salvation. It is bound to be narrow at the outset. But as we progress in this way of life and in faith, we shall run on the path of God’s commandments, our hearts overflowing with the inexpressible delight of love.[16]

Benedict has embarked on a thoroughly biblical, gospel-centered, Jesus-honoring project of taking the follower of Jesus and giving them a concrete path down which to walk, tutoring their hearts both to perceive the voice of God and to “inexpressibly” love what they hear such that, their wills at the ready, they obey what they have heard Our Lord speak. Although this is found in a monastic rule, this description sounds like nothing other than the Christian life.

Also notable is that the Prologue to St. Benedict’s Rule contains the only real explicit doctrinal teaching of the entire document. All action embodies belief, so it would be right to say that the rest of his Rule assumes certain doctrinal perspectives; but it is rare that they are explicitly articulated even as Holy Scripture is relied on heavily to support the structure and organization of Benedict’s cenobitic communities. St. Benedict is primarily concerned with one thing: progression in the Christian life. We will return to this feature of doctrinelessness in due course.

After identifying the different kinds of monks (Ch. 1), the kind of person the abbot ought to be (Ch. 2), and who should be present to determine more and less important community matters (Ch. 3), Benedict’s fourth chapter enumerates what he calls “the tools of the spiritual craft.”[17] The first tools are the greatest and second commandments, to love God and to love one’s neighbor as oneself; from the Ten Commandments, murder, adultery, stealing, coveting, and bearing false witness are listed; Peter’s exhortation to honor everyone is now Benedict’s; also to be used are renunciation of self, buffeting one’s body, avoiding self-pampering and loving fasting. In addition to these, one must relieve the lot of the poor, clothe the naked, visit the sick, bury the dead, and console the sorrowing. Dozens more tools, lifted almost verbatim from the pages of Scripture – especially the New Testament, but with references to the Prophets, Psalms, and Apocrypha as well – fill the monastic tool bag.

Tools. Craft. A workshop “where we are to toil faithfully at all these tasks.” The business of following Jesus is work, an image that Benedict depends on and for good reason – not only was Jesus a tradesman in His earthly life, but He also often described apostolic labors and the kingdom duties of His followers using the trades: fishermen, shepherds, stonemasons, and farmers are frequently found in His teachings and parables. It might be tempting to say that the labor imagery is used simply to convey the idea of effort, but consider that in the parable of the wise man that built his house on the rock, he had some knowledge of the structural soundness of a rock such that he would choose to build on it rather than sand; Jesus relied on the skill and attentiveness of the shepherds in His parables of sheep; farmers and vinedressers that were capable of cultivating abundant harvest were held up as the ideal. It is not merely the fact of laboring, then, that we should take from Christ’s teachings or Benedict’s Rule, but skilled labor plied with trained hands.

A central feature of Benedictine spirituality is what Benedict calls the opus Dei, the “work of God.” Is it surprising that we should find work at the heart of a manual for spiritual laborers? Just how high a value does Benedict place on this work? “Nothing is to be preferred to the work of God.”[18] There is nothing more valuable, nothing that is to take precedence, nothing that can displace this most essential of labors: the public prayer of the monastic community. The Psalter is chanted in its entirety weekly, with generous portions of the Old and New Testaments and the Gospels read daily. The prayer of the Daily Offices is called the work of God by Benedict, says Br. Demetrius R. Dumm OSB, because it refers to “God’s prior claim on human activity as opposed to merely human projects or ambitions.”[19] Of all the other things a monk might do in a day in an effort to meet the needs of his monastery or the surrounding secular (that is, non-monastic) community, the Daily Office is there as an ongoing work into which they are invited to participate. All work in the world ought to be indexed to God, since it is in Him that we “live, and move, and have our being.”[20] Prayer is the pure enactment of that fact. So important is the work of God that the details of its structure – the daily timetable and its seasonal changes, expectations for arrival and dismissal, consequences for incorrectly or improperly or irreverently chanting the prayers – occupies twelve of the seventy-two chapters of Benedict’s Rule. Br. Demetrius draws out another helpful insight from this about the way Benedict conceptualizes time.

Time is one of the most precious gifts that we humans receive from God. It is clear that Benedict wants his monks to acknowledge this gift by returning choice portions of their time each day to God. In this way, they will practise the most basic form of hospitality, which is to make room in their schedules for the entertainment of God’s real but mysterious presence. All other forms of hospitality…derive from this profound respect for the mystery of God.[21]

The arrangement and use of time, then, is a central focus of Benedictine spirituality. The hospitality brothers are expected to show one another and guests of the monastery, articulated more fully in chapter 53 of the Rule when Benedict says, “All guests…are to be welcomed as Christ,” is habituated by first opening their schedules to the Presence of God in the daily prayer offices.

Prayer is the central work, but is it the only work? Certainly not! The Benedictine motto ora et labora, prayer and work, gestures towards another hallmark of the way in which the monk lives out their apprenticeship to Jesus – manual labor. “Idleness is the enemy of the soul,” Benedict tells his monks in chapter 48. “Therefore, the brothers should have specified periods for manual labor as well as for prayerful reading.” After all, there are physical needs to be met in the shared life of the cenobitic community: food needs cooking, garments need washing, pipes need mending, fields need cultivating. So important are the tools and implements of the monastery that the monk “will regard all utensils and goods of the monastery as sacred vessels of the altar,”[22] which is to say both that their labor is always done in the Presence of God and that God is the one for whom they are laboring, even in the apparently mundane or routine tasks of their day. When one thinks of what gives the life of a monk its distinctness, prayer is likely the first thing to come to mind. Considering that prayer is called the “work of God,” this would not be inappropriate. Work might come to mind second simply based on the reality of human need. But in chapter 48 of the Rule, Benedict makes this rather surprising statement: “When they live by the labor of their hands, as our fathers and the apostles did, then they are really monks” (emphasis mine).[23] We might want to say that prayer is what distinguishes the monk as a monk, but in Benedict’s mind it is their life of labor that makes them truly monastic because it follows the Deserts Fathers who were following the apostles who, as Paul said, was following Christ. Notice also “prayerful reading”: this was not a communal activity, but time for the monk to privately address his interior needs as an individual, separate from the liturgical modes of prayer found in the daily offices/work of God and the weekly celebration of the eucharist. The monk’s labor happened spiritually and physically, communally and individually, and all of it for God’s sake.

To summarize what has been said thus far: Benedictine spirituality formed the religious ecosystem in which the Anglican tradition took shape. Benedict desires to help willing Christians walk – no, run! – down the path of God’s commandments and to progress in the Christian way of being human in this world. To aid in this goal, Benedict structures a community of Jesus-followers in which everything from when they rise and take their rest, what they wear and how they wear it, regulations about food and travel – absolutely everything is designed to be conducive to growth in Christian virtue. Indeed, sanctification is Benedict’s architectonic design principle. He gives those apprenticed to Jesus tools to toil in their spiritual craft, which are either direct quotes from the pages of Scripture or abstracted principles taken therefrom, to guide the development of their interior worlds, their virtue, their holiness, under the direction of the abbot and shoulder-to-shoulder with their fellow apprentices. The work that he outlines involves both spiritual labor (in the daily offices, the celebration of the eucharist, and personal devotion like lectio divina/“spiritual reading”), and manual labor. All this work, whether material or immaterial, mundane or sublime, is done in such a way as to maintain an awareness of and a self-direction towards God, welcoming Him into every moment of time and every act of the body. Ora et labora is the Benedictine motto for good reason.

Anglicanism as Apprenticeship: The Book of Common Prayer and the Anglican Parish

Just as a document was our way into discussing the Benedictine spirit, so too will a document lead into our discussion of Anglican spirituality. The Book of Common Prayer is the crown jewel of the Anglican tradition, and while there are many features to be analyzed to fully appreciate its majesty, for the purposes of this essay we will look at it as in the same category as the Rule of St. Benedict: a book of ascetical theology. “Ascetical theology” here will be defined in the Thorntonian way, as “dealing with the fundamental duties and disciplines of the Christian life, which nurture the ordinary ways of prayer, and which discover and foster those spiritual gifts and graces constantly found in ordinary people.”[24] For Thornton, an “ascetic” is not one who engages in extreme or austere demonstrations of self-denial, but the one who prays; for him, ascetical theology is primarily a process rather than a subject, and if it is a subject at all, it is only so secondarily. Good ascetical theology is concerned with living out the Christian life. He says, “Ascetical theology makes the bold and exciting assumption that every truth flowing from the Incarnation, from the entrance of God into the human world as man, must have its practical lesson. If theology is incarnational, then it must be pastoral.”[25] Perhaps we could rewrite Jesse Bertron’s poetic verse, referenced above, thusly, “in His flesh is a silver nail/that shines like a lamp/and underneath is the hand I read.” The Word’s body as a text to be read. Like Benedict’s Rule, then, the Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is concerned not so much with the theoretical subject of what living a Christian life might look like or with articulating abstracted theological principles, but with arranging the tools the use of which constitutes the Christian life and handing them over to the apprentice of Jesus.

We noted in the discussion of St. Benedict’s Rule that it was largely a doctrineless document, and this definition of ascetical theology goes a good distance in explaining why. The Rule is meant to direct theologically informed action. It is not that doctrine is not needed – it underpins the whole project – but doctrine itself grows as an articulation of the life of God in the lives, individually and corporately, of Christians. There is a real sense in which language does not make sense until one has undergone the experiences to which the language refers. The BCP goes a bit further than the Rule in that it actually contains the historic Creeds in its pages, although the assumption of the Rule is that by participating in the liturgical life of the Church, the monks would be exposed to and contemplating and, most importantly, living according to them. As Forde stated in his quote at the beginning of this essay, it is easy enough to define sanctification and many traditions and documents have done so, but it is much harder to give good instruction in living according to Christ who is our sanctification.[26] The Rule and the BCP both give us the tools to accomplish the latter.

The Book of Common Prayer does not make any attempt at hiding its intended design or use – the Christian is to take it up and pray. In what environment? As its name suggests, the commons. By “common” is not meant “found or done often” (although, please God, may it be so); but rather its secondary meaning in modern parlance of “being shared by more than one.” The BCP is intended to be the prayer of a community, to draw them into a shared religious ecosystem, to shepherd them into this commonly held task. Some Christian traditions establish the shape and boundaries of their ecclesial bodies by demarcating doctrinal standards, others by drawing lines around important historical moments, and yet others by particular activities of God experienced amongst their members. Often, these are codified in a textual form. But the defining feature of Anglicanism is a text that is not simply meant to be read: it is to be enacted. Beneath the text and growing from it is work. The work of God. The BCP, then, is a sort of toolbox that contains in it many of the tools that the Anglican Christian uses to accomplish the labor of their spiritual craft. Services, ceremonies, the Psalter, a kalendar of feasts and fasts, propers, the Daily Office, litanies, collects, sacraments, rubrics. These all come together to create an entire ascetical system which addresses the whole of a person’s spiritual life and send them “running down the path of God’s commandments, hearts overflowing with the inexpressible delight of love,” as Benedict has it. At the heart of everything else a Christian might need to do in the course of their day is God’s prior claim to all human activity, prayer, which brings about the conversatio morum, the conversion of life, that Benedict, and therefore Anglican spirituality, values.

The Benedictine project of establishing a “school for the Lord’s service” resulted in a great many things, but articulating a threefold rule of prayer – Office, eucharist, and personal devotion – is perhaps the most important. It is the ascetical system that the BCP now enshrines. And just as the monastery was a community for sharing a common Christian life and the work appropriate to it, the BCP properly belongs to a community sharing in common Christian life and the work appropriate to it. The ascetical riches mined by the Benedictines are inherited by the Anglican parish whenever its clergy and parishioners structure their lives according to the BCP and use it, not as a book of one-off prayers and services, but as an ascetical system. Whereas in the past this ascetical system in its fullness was available only to those would voluntarily enter the vowed life of the monastic community, this system is now made available to anyone that will voluntarily participate in the parochial life of the local Anglican church that has the BCP at its center. Put another way, the one desiring to apprentice themselves to Jesus need look no further than the workshop of the Anglican parish to learn and ply their spiritual trade.

According to philosopher Richard Sennett, a workshop is “a productive space in which people deal face-to-face with issues of authority…in the flesh.”[27] This definition is helpful because it implies that there is a non-negotiable element of embodiedness that must incarnate the work so that it might be seen, duplicated, critiqued, improved upon, and perfected. As Thornton pointed out in his definition of ascetical theology, it is precisely the Incarnation of Jesus Christ that means there is need for pastoral direction in the practical matters of the Christian life. God assumed our humanity and worked; we too must be human as He was human and work. Christianity is not a Gnostic religion that subsists in disembodied ideas and consists of the acquisition of secret knowledge, but a “pure religion”[28] that subsists in a hypostatically embodied God and therefore consists of concrete-yet-spiritual actions in the world. The fruit of the Spirit enumerated by St. Paul to the Galatian believers are virtues, good moral habits which others can only know that one possesses if one acts in accordance with them. One can only know that another is loving if they find themselves in a situation that demands love. So it is with the rest of the fruit. Implicit in this agricultural analogy is the necessity of cultivation, of guidance, of pruning and nourishment and structure. In the monastery, it is the task of the abbot to guide the growth of the monk; in the parish, it is the task of the clergy, of catechists and spiritual directors (often mature laypeople), to guide the growth of the Christian, “for the perfecting of the saints, for the work of the ministry.”[29] Those who have “authority in the flesh” as given by God through the church (in the case of clergy), recognized by those in the community, and as identified by comparison to the ideals of the spiritual craft have the moral imperative to teach the less mature and lead them down the path of holiness.

At a certain point, practice needs the help of verbal support to articulate and frame in the ideas being enacted, but it is often the case that the language used to provide this support will not make sense until one has taken a fair crack at the task. This is where the secondary sense of ascetical theology as a subject (rather than a process) is helpful. It is the assumption of the Anglican way of being Christian, following the Benedictine tradition that nurtured it, that growth in the Christian life is possible, that we may actually labor in our soul-fields – always according to the kindness and grace of God – to raise up a harvest of holiness and virtue. In a very Augustinian moment, Benedict says to his monks, “If you notice something good in yourself, give credit to God, not to yourself, but be certain that the evil you commit is always your own and yours to acknowledge.”[30] The Anglican tradition has a long list of divines writing manuals in this secondary mode of ascetical theology, articulating the virtues and vices to toiling souls, illuminating the mechanics of the interior life, and suggesting practices fit to soulish tasks. The goal? To grow a sensitivity to God’s presence such that all human activity might become prayer.

One such work was published in 1650 by the Caroline Divine, Jeremy Taylor. In his The Rule and Exercises of Holy Living, Taylor has given the church a manual for leading a holy life. We gather as a parish for liturgical prayer in the Offices and the celebration of the Eucharist, but what about the rest of the week? Taylor makes explicit what was implicit in Benedict. “God hath not only permitted us to serve the necessities of our nature, but hath made them to become parts of our duty; that if we, by directing these actions to the glory of God, intend them as instruments to continue our persons in His service, He, by adopting them into religion, may turn our nature into grace, and accept our natural actions as actions of religion. …And there is no one minute of our lives…but we are or may be doing the work of God…”[31] Taylor has already enjoined his reader to set as much time as possible aside to “be spent in the direct actions of devotion and religion” – perhaps we can read in this two of the threefold rule – and yet even for those times which may not be filled with such direct religious activity, he reminds the reader that God kindly accepts the mundane tasks of daily life as being unto Him. His text sets out three principles: 1) We ought to set aside as much time as possible for devotion to God, 2) We won’t be able to set aside much time, but God accepts other, natural actions as actions of religion, and 3) Regardless of what kind of action one makes, one always stands before God. “I shall, therefore…reduce these three to practice, and shew how every Christian may improve all and each of these to the advantage of piety, in the whole course of his life; that if he please to bear but one of them upon his spirit, he may feel the benefit, like an universal instrument, helpful in all spiritual and temporal actions.”[32] Only a few pages into his work Taylor has already invoked three very Benedictine ideas: the arrangement of time, the use of tools/instruments, and the work of God. In another very Benedictine moment, Taylor offers the following advice in a section on prayer: “Whatever we beg of God, let us also work for it, if the thing be matter of duty, or a consequent to industry; for God loves to bless labour and to reward it, but not to support idleness.”[33] Ora et labora is alive and well in at least one of the Caroline Divines. He also addresses wandering thoughts during prayer and makes a point of saying later in the same section that private prayer wanes when Christians “love not to frequent the sacraments, nor any of the instruments of religion, as sermons, confessions, prayers in public [the Daily Offices], fastings; but love ease and a loose undisciplined life.”[34] Whatever individual religious piety may consist of, it is dependent for its existence on participation in the ascetical life of the parish centered on the BCP. Thornton makes a similar point when he summarizes what he sees as St. Benedict’s “most vital message to the Church to-day: that loyalty to this basic threefold Rule—Mass, Office, devotion—is always the prior ascetical discipline.”[35]

Another text that leans more heavily into the secondary meaning of ascetical theology by a thorough analysis is H.R. McAdoo’s The Structure of Caroline Moral Theology. It is not likely all that helpful except to clergy and the interested layperson, but in it McAdoo makes a number of helpful statements that articulate another facet of the Benedictine disposition that shows up in Anglican spirituality. Speaking of Caroline piety, he says, “The Divine Life in daily life might be its guiding maxim. But if it is much concerned with the pots and pipkins of religion, Caroline piety is not forgetful of the highest levels of the spiritual life and labours to develop in men the faculty of seeing their daily conduct and devotional exercises in the light of their eternal destiny.”[36] The manual labor of the Benedictine monk was never merely manual labor. His hammer or knife or habit was to be treated as if it were a chalice or paten or thurible. This outlook was received by Anglican spirituality wholesale. One example that McAdoo points to is the nature of repentance. Up to the Caroline age, repentance had been dominated by the Roman view which located Christian moral activity in the sacraments, so true repentance was to be found in the sacrament of penance. The Caroline position was to accept that repentance was, of course, found in the sacrament of penance, but, contrary to Rome and in accordance with Scripture, to reject the sacrament as being the only place to enact the doctrine of repentance. “At once, we may trace the fundamental cleavage of opinion to the Caroline refusal to ground the doctrine of repentance on the sacrament of penance. It is a refusal which typifies the Anglican attempt to enlarge the scope of moral theology by no longer confining it to the confessional.” [37] We may see in this an example of the even wider Anglican impulse to leverage all the matters of daily life for spiritual benefit, an impulse which is itself very Benedictine. Benedictine communities pay attention to the physical environment as a reminder to pray. This is the practice of “recollection,” wherein the material conditions of the surrounding environment, an affective movement of the heart, or anything in between may spur the soul on to prayer. Anglican parish life shares in this: one can notice in writers like Margery Kempe or Father Andrew, S.D.C. the inclination to see the everyday circumstances of Nazareth in one’s own everyday circumstances, taking the stuff of daily life and turning it into prayer or devotion or holy work. Trade environments are designed with a sort of gravity that constantly pulls the apprentice into its orbit. The order and arrangement of the shop environment acts as a constant reminder to the apprentice what work is to be done, in what sequence, and towards what end. This attention to one’s circumstances to spur on and direct work is shared by the Anglican spiritual pedigree.

Thornton points out that Benedictine communities “breathe a sane ‘domestic’ spirit” which have a pastoral orientation, the Rule being a “little rule for beginners” rather than a post-doctoral course in spirituality. Anglicanism tends to have this same domestic spirit, creating guides (some of which we have already looked at) to help parishioners in their Christian growth, some even going so far as to include “directions for such as cannot read,” recruiting the charity of the literate to read to their illiterate brethren that they might know their duty and how to accomplish it as well. “Like the Christian faith itself,” says Thornton, “both St. Benedict and the Prayer Book are capable of nurturing saintly doctors and saintly illiterates.”[38] At the risk of playing into blue-collar stereotypes, it is worth noting that the trades also have this in their favor, that they are accessible to both the literate and the illiterate, creating of both masters of the trade worthy of emulation. We might also note here that, regardless of education level, the abbot and monk are bound by the same strictures. The most veteran brother and the discerning novice are both expected to abide by Benedict’s Rule. And so it is within the Anglican fold that clergy and laity, king and peasant, are all bound by the same rule. Morning and Evening Prayer, the feasts and fasts of the kalendar, the sacraments and rites of the Church, matrimony and burial: they are common to all those who find themselves in the care of the Anglican parish and all alike are expected to share in the work. So, too, in a trade. Master and apprentice are bound by the same rule, the same standards and ideals, the same tools and techniques, the same traditions and sciences and customers.

Anglican spirituality succeeds in the goal of Christian progress for the same reason that Benedictine spirituality succeeds—they both function as an apprenticeship. Let us now make clear what has been mentioned and hinted at until this point. Apprenticeships are a recurring didactic model that have four key features: they are liturgical, filled with rites and actions that accord with the ideals of the trade and form the apprentice such that they become a suitable vessel for the craft; they give priority to labor, hands-on practice in the built environment with the use of tools; they support their labor through analytical thought codified in trade-specific, meaning-dense language; and they seek to tradition their craft to the learner in an environment shaped by love—for the craft, for fellow craftsmen, and for whom the work is plied. There is an assumption in the trades that the apprentice intends to grow and to learn, to in some sense cease to be an individual and submit themselves to its structures and demands. Philosopher Matthew B. Crawford gives the example of a student learning to play an instrument. “Her obedience,” says Crawford, “is to the mechanical realities of her instrument, which in turn answer to certain natural necessities of music that can be expressed mathematically. For example, halving the length of a string under a given tension raises its pitch by an octave. These facts do not arise from the human will, and there is no altering them. The education of the musician sheds light on the basic character of human agency, namely that it arises only within concrete limits…[T]hese limits need not be physical; the important thing is rather that they are external to the self.”[39] This sounds very much like the conditions set by Benedict who places heteronomous limitations on his monks and a high value on obedience to the abbot in near-abandonment of the will, or more precisely, the total abandonment of self-willing. In Anglicanism there is a distinct anti-clerical streak that is nevertheless balanced by obedience to the bishop and the threefold rule as contained in the BCP. There is no room for the exertion of the autonomous self unless and until that self has been so formed by heteronomous limits, so shaped by the “mechanical realities” and “certain natural necessities” of the workshop and the work, that their desires and actions are expressions of the ideal. We might say they have become one with the craft. One simply acts as a Benedictine, as an Anglican, as a plumber, as a Christian.

Perhaps these four features of apprenticeship – liturgy, labor, language, and love – are only one piece of the puzzle. Might it be that in order for the apprenticeship model to work, the apprentice must be a particular kind of person? In possession of a particular virtue? What quality must a person possess to die to the liberal, autonomous, unencumbered self and submit themselves to a heteronomy of any kind? To “lose their life for My sake” and once again “find it”?[40] Can it be that apprenticeship, as effective a model as it is in its own right, is made all the more effective because it demands humility as the price of entry? Indeed, humility is the topic of the longest chapter of St. Benedict’s Rule. The Book of Common Prayer is shot through with prayers of humility: penitence and mourning and access and thanksgiving. The trades, as Crawford points out, require no less than a humble approach to the limitations enforced by craft and matter. “Humility” comes from a Latin word, “humus”, which means “ground.” “Humus” is also the word we still use to refer to the organic material in soil. Humus is nutrient rich and retains moisture. It gives soil its fecundity and capacity for growth. Interestingly, there is another modern term the reader may recognize from this Latin word family— “human.” Could it be that just as humus is the condition for growth in the soil, humility is the condition for growth in the soul? Benedict and the BCP seem to think so.

For the soul that is struggling to understand why they have made no progress in holiness despite their love for Jesus; for the soul that has sought wise counsel from their elders only to meet sheepish admissions of incompetence or unwillingness to help; for the soul that has asked how they may grow into the “measure of the fulness of the stature of Christ”[41] and received the well-intended but trite response, “Just read your Bible and pray”; for the soul that has read in the Bible’s pages that they are to mortify the flesh, make of their limbs tools of righteousness, buffet their body, and walk in righteousness; for the soul that has prayed that they might be what Christ paid for them to be by His incarnation, life, suffering, death, descent into hell, resurrection from the dead, and ascension into heaven; for the soul that has heard the Apostle’s instruction to “pray without ceasing” but cannot fathom how this is possible; for the soul whose eyes well with tears when they hear Benedict say, “As we progress in this way of life and in faith, we shall run on the path of God’s commandments, our hearts overflowing with the inexpressible delight of love”—there is a path to walk down, a way to travel, and it is available to anyone that finds themselves near a prayer book-loving Anglican parish. Go there and become an apprentice of the carpenter king.

NOTES

- Gerhard O. Forde, Christian Spirituality, (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1988) pg. 78 ↑

- Rom. 7:23, KJV ↑

- 1 Pet. 5:8, KJV ↑

- Eph. 6:12 KJV ↑

- 1 Thess. 4:11, KJV ↑

- 2 Thess. 3:12, KJV ↑

- “A more satisfying definition of the workshop is: a productive space in which people deal face-to-face with issues of authority. This austere definition focuses not only on who commands and who obeys in work but also on skills as a source of the legitimacy of command or the dignity of obedience. In a workshop, the skills of the master can earn him or her the right to command, and learning from and absorbing those skills can dignify the apprentice or journeyman’s obedience. . . .The successful workshop will establish legitimate authority in the flesh, not in rights or duties set down on paper” (emphasis mine). Richard Sennett, The Craftsman, (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2008), pg. 54 ↑

- Jesse Bertron, A Plumber’s Guide to Light, (Rattle Magazine, 2021), pg. 2 ↑

- St. Benedict, The Rule of St. Benedict in English, (Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1981) pg. 15 ↑

- Col. 1:13, KJV ↑

- Rom. 6:13, KJV ↑

- Benedict, 16-17 ↑

- Matt. 7:24-25, KJV ↑

- Benedict, 18 ↑

- Ibid. 18 ↑

- Ibid. 19 ↑

- Ibid. 29 ↑

- Ibid. 65 ↑

- Demetrius R. Dumm OSB, “The Work of God.” The Benedictine Handbook, Liturgical Press, 2003, pg. 103 ↑

- Acts 17:28, KJV ↑

- Liturgical Press, 103 ↑

- Benedict, 55 ↑

- Ibid. 69 ↑

- Martin Thornton, English Spirituality, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cowley Publications, 1963), pg. 19 ↑

- Ibid. 21 ↑

- Cf. 1 Cor. 1:30 ↑

- Sennet, 54 ↑

- James 1:27, KJV ↑

- Eph. 4:12, KJV ↑

- Benedict, 28 ↑

- Jeremy Taylor, The Rules and Exercises of Holy Living, (Cleveland/New York: The World Publishing Company, 1956) pp. 5-6 ↑

- Ibid. 6 ↑

- Ibid. 237 ↑

- Ibid. 245 ↑

- Thornton, 79 ↑

- H.R. McAdoo, Ph.D., The Structure of Caroline Moral Theology, (New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1949) pg. xi ↑

- Ibid. 122 ↑

- Thornton, 259 ↑

- Matthew B. Crawford, The World Beyond Your Head, (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015), pg 128 ↑

- Matt. 16:25, KJV ↑

- Eph. 4:13, KJV ↑

'Anglicanism: Apprenticeship to the Carpenter King' has 1 comment

July 4, 2024 @ 11:19 am Eric Blauer

Thank you for this deep, rich and meaningful piece of spiritual and practical reflection. I am not Anglican, but the BCP and retreats at Benedictine Abbeys are part of my Evangelical, Charismatic, Nondenominational practice of faith both individually and pastorally. I will be gnawing on many pieces of this meaty post and sucking out the marrow of that which I can break open.