One of the hottest debated questions among Anglicans is the doctrine of the Eucharist, or, as the Articles of Religion refer to it, the Lord’s Supper. When I began investigating the Anglican tradition, what I discovered sent me down a path of reformation and renewal. Rather than looking to the Lutherans, Eastern Orthodox, or Roman Catholics for Eucharistic teaching, I wanted to know what our own Protestant Reformed tradition[n] taught according to our historic Formularies and conforming Anglican Divines. Article 28 of the 39 Articles lays out three propositions we are concerned with:

- The Supper of the Lord is a Sacrament of our Redemption whereby those who receive worthily, by faith, partake of Christ’s Body and Blood.

- There is no transubstantiation of the elements, only a sacramental mutation of the elements, a sacramental union of the signs of bread and wine with the body and blood signified.

- The true Body of Christ is given, taken, and eaten in a heavenly and spiritual manner by the mouth of faith, not carnally by the mouth of the body.

Article XXVIII, Proposition I

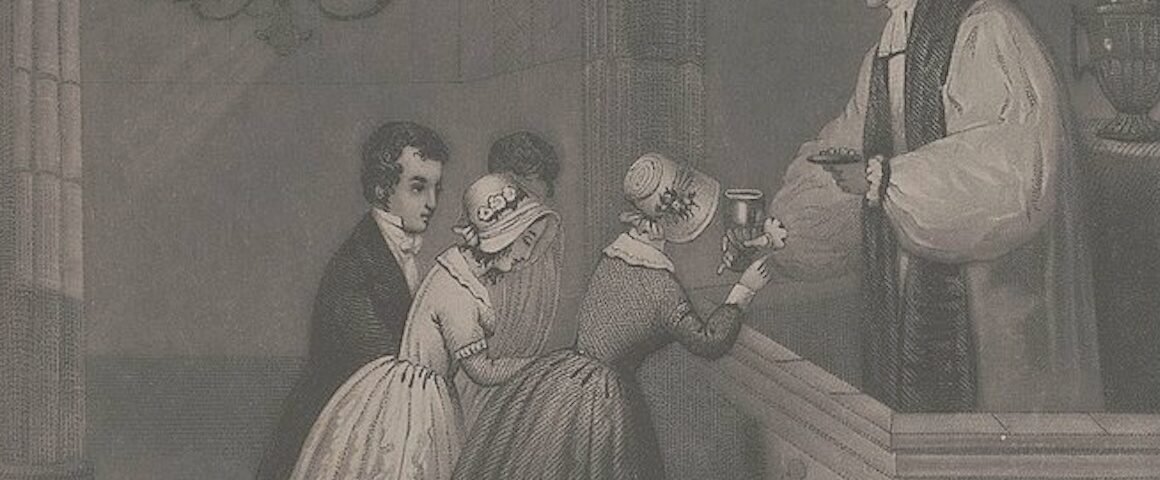

The first proposition deals with the question of what the Sacrament is first and foremost. As a young Baptist, I was taught that it was a memorial meal, where we took the bread, drank the grape juice, and thought about what Jesus did for us. What is it for Anglicans? The first place every Anglican should look is the Book of Common Prayer, in this case, the 1662 International Edition.

Before the Communion.

O Lord Jesus Christ, who has ordained this holy sacrament to be a pledge of thy love, and a continual remembrance of thy passion: Grant that we, who partake thereof in faith, may grow up into thee in all things until we come to thy eternal joy, who with the Father and the Holy Ghost livest and reignest, one God, world without end. Amen[1]

We see here that the Lord’s Supper is a memorial meal that calls us to honor the body beaten and hung on the cross and blood poured out for the sins of the world. In the Catechism, we see that the Lord’s Supper is ordained “for the continual remembrance of the sacrifice of the death of Christ”[2], stated so clearly that no Anglican can avoid the truth that this Sacrament is a covenant, memorial meal just as the Passover Lamb meal was for the ancient Israelites. However, we confess, as we have always confessed, that this is not all:

The Prayer of Humble Access

We do not presume to come to this thy table, O merciful Lord, trusting in our own righteousness, but in thy manifold and great mercies. We are not worthy so much as to gather up the crumbs under thy table. But thou art the same Lord whose property is always to have mercy. Grant us therefore, gracious Lord, so to eat the flesh of thy dear Son Jesus Christ, and to drink his blood, that our sinful bodies may be made clean by his body, and our souls washed through his most precious blood, and that we may evermore dwell in him, and he in us. Amen[3]

From the pen of the Most Rev. Dr. Thomas Cranmer, we learn that those who come to the Holy Table and receive the bread and the wine “rightly, worthily, and with faith”[4] partake of Christ’s very Body and Blood. The Catechism holds to this truth, telling us that the inward part or thing signified is “the body and blood of Christ, which are verily and indeed taken and received by the faithful”[5]. Next, in addressing propositions two and three, we will learn how Christ is present and how we partake of him during the Supper of the Lord.

Article XXVIII, Propositions II & III.

The teaching of the Eucharist that I will explain here is the classical Anglican doctrine recovered from the early Church, developed and taught by our conforming theologians. We Anglicans believe that Christ is really, that is truly, present in the Eucharist, but we speak “not of Christ’s carnal presence. . . but sometimes of his sacramental presence”[6]. By sacramental presence, I mean “through signification; as meaning exists in speech or writing, namely that it is signified by them but does not lie hidden under them”[7]; however, this is not meant to suggest a bareness or emptiness of the symbols for “we do not set down here any common signification, but a sacramental, powerful, and effectual signification, by which believers are incorporated into Christ”[8]. When the Minister consecrates the elements of bread and wine by the word and institution of God, “the substance of bread and wine remain in the Lord’s Supper”; however, there is a “sacramental mutation of the same into the body and blood of Christ”[9]. Where once were mere symbols, there is affected a sacramental union as “these two things (that is to wit, the thing signified, and the sign that signifieth) be concurrent and inseparable” by which the signs “bring the things signified into our hearts”[10]

When you take the sacrament in remembrance that Christ died for you, with a repentant heart and humble faith, you are spiritually and truly fed by Christ’s body and blood. A spiritual feeding means that it is not a physical eating of Christ’s natural body or drinking his natural blood, but a union with Christ through faith, not for nourishment of body but of soul. It is for this reason that we must eat by the duplex os fidelium[11], the double mouth of the faithful because “by faith at this his table we receive not only the outward sacrament but the spiritual thing also”[12].

Notice that faith is so important not because the presence of Christ is not truly exhibited to us or conveyed to us: “I acknowledge that we truly receive the res sacramenti, that is the body and blood of Christ”[13]. As John Jewel so eloquently explained:

But thus much he must be sure to hold, that in the supper of the Lord there is no vain ceremony, no bare sign, no untrue figure of a thing absent, but as the Scripture saith: ‘The table of the Lord, the bread and cup of the Lord, the memory of Christ, the annunciation of his death,’ yea, ‘the communion of the body and blood of the Lord’ in a marvelous incorporation, which by the operation of the Holy Ghost, the very bond of our conjunction with Christ, is through faith wrought in the souls of the faithful, whereby not only their souls live to eternal life, but they surely trust to win to their bodies a resurrection to immortality.[14]

The teaching on the necessity of faith persisted with the Caroline Divines; the Right Rev. Dr. John Cosin taught, “our faith doth not cause or make that presence, but apprehends it as most truly and really effected by the word of Christ.”[15] Therefore, let us not be dismayed over the necessity of faith but trust that “the sacrament of the body and blood of Christ hath a promise annexed, which the priest should declare in the English tongue. ‘This is my body, that is broken for you.’ ‘This is my blood, that is shed for many, unto the forgiveness of sins.’ ‘This do in remembrance of me,’ sayeth Christ, Luke 22 and 1 Cor. 11.”[16]

A common objection to the pneumatic or spiritual presence and feeding described here is that it is somehow false or imaginary. This could not be further from the truth; according to the Reverend Richard Hooker, “his flesh and blood are truly and not imaginarily meat and drink. Through faith we truly perceive the very taste of eternal life in the body and blood sacramentally presented, discerning that the grace of the Sacrament is as truly present as is the food which our mouths eat and drink”[17] Jacobian Divine, the Right Rev. Dr. Lancelot Andrewes stated the same, saying that the body and blood of Christ is “not only represented therein, but even exhibited to us. Both which when we partake, then have we a full and perfect communion with Christ this day.”[18]. Before them, the Right Rev. John Jewel taught “that in the Lord’s supper there is truly given unto the believing the body and blood of the Lord.”[19]

It is left to me to explain spiritual presence, as I have previously explained sacramental presence. In the negative, we deny any corporeal presence of Christ’s natural flesh and blood, for “the natural body and blood of our Saviour Christ are in heaven, and not here.”[20]. In the positive, we can look to Edwardian Divine, the Rev. Dr. Peter Martyr Vermigli, who said, “it is said, Sursum Corda, when you lift up your mind from [the Signs] to the invisible things offered you” which he taught looking to St. Chrysostom’s The Priesthood III, 4, where he wrote “do you not rather think that you are translated into heaven? And casting off all carnal thoughts, with disembodied spirit and pure mind contemplate the things that are in heaven?” Vermigli elaborated this belief to Archbishop Thomas Cranmer explaing, “if by presence someone understands the perception of faith by which we ourselves ascend to heaven, by mind and spirit embracing Christ in his majesty and glory, I willingly consent to him” and all this by the power of the Holy Ghost[21]. Caroline Divine, the Right Rev. Jeremy Taylor taught this same sense of spiritual presence, saying, “By ‘spiritually’ we mean, ‘present to our spirits only;’ that is, so as Christ is not present to any other sense but that of faith or spiritual susception.”[22]

The final sense I will discuss of this word spiritual will help us in understanding Christ’s personal presence with and in the communicant despite the heavenly location of his natural, human body. The Right Rev. Nicholas Ridley wrote in his A Brief Declaration of the Lord’s Supper:

By grace the same body of Christ is here present with us. Even as, for example, we say the same sun, which in substance, never removeth his place out of the heavens, is yet present here by his beams, light, and natural influence, where it shineth upon the earth. For God’s word and his sacraments be, as it were, the beams of Christ, which is Sol justitiae, the Sun of righteousness.[23]

This very same idea of presence by blessings and grace was taught by his close friend, Thomas Cranmer, when he wrote about Christ’s spiritual presence:

My meaning is, that the force, the grace, the virtue and benefit of Christ’s body that was crucified for us, and of his blood that was shed for us, be really and effectually present with all them that duly receive the sacraments.[24]

Richard Hooker matured this teaching in the fifth book of his Laws, teaching that even though Christ’s natural human body, blood, and soul are not locally present in the elements of the Eucharist, “for the actual position of Christ’s manhood is restrained and tied to a certain place,” he is still personally and wholly present in the use of the Supper “by conjunction with deity that extends as far as deity.”[25] Richard Hooker explains this sort of presence by the conjunction of the divine and human natures of Christ by explaining that He is present,

as God by essential presence with all things; as man by cooperation with that which is essentially present; the soul of Christ is present by knowledge and assent with all things which his deity works. His bodily substance has a presence of true conjunction with deity everywhere and by virtue of that conjunction has been given a presence of power and efficacy.[26]

The Right Rev. Jeremy Taylor said the same about spiritual presence by explaining “we affirm Christ’s body to be present in the sacrament: not only in type or figure, but in blessing and real effect.[27] Following after him we have Bishop John Cosin in agreement when he explained the mystic presence of Christ as, “the properties and effects of what they represent and exhibit, are given to the outward elements,” elaborating that Christ did not teach what the elements were by nature or substance but “as what is there use and office and signification.”[28]

Therefore, let it suffice to say that Christ, while not locally present according to his natural body and blood, is spiritually, mystically yet truly present in the use of the Sacrament, best searched for not in the elements but in the souls of those who receive this moral instrument by faith.[29]

Notes

n) The British Monarch Coronation Oath Act of 1688: Will You to the utmost of Your power Maintain the Laws of God the true Profession of the Gospel and the Protestant Reformed Religion Established by Law?

- Samuel L. Bray and Drew Nathaniel Keane, The 1662 Book of Common Prayer: International Edition (InterVarsity Press, 2021), 699.

- Ibid, 305.

- Ibid, 261.

- Ibid, 640.

- Ibid, 306.

- Thomas Cranmer, The True & Catholic Doctrine of the Lord’s Supper (New Whitchurch Press, 2020), 10.

- Peter Martyr Vermigli, The Oxford Treatise and Disputation on the Eucharist, trans. Joseph C. McLelland (The Davenant Press, 2018), 218.

- Ibid, 284.

- Cranmer, The True & Catholic Doctrine of the Lord’s Supper, 80.

- William Tyndale, The Complete Works of William Tyndale, The Supper of the Lord, ed. The Parker Society (CrossReach Publications, 2022), 364.

- Vermigli, The Oxford Treatise and Disputation on the Eucharist, xxxix.

- John Jewel, The Books of Homilies: A Critical Edition, An Homily of the Worthy Receiving and Reverent Esteeming of the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ, ed. Gerald Bray (James Clarke & Co, 2015), 431.

- Vermigli, The Oxford Treatise and Disputation on the Eucharist, xxxvi.

- Jewel, An Homily of the Worthy Receiving and Reverent Esteeming of the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ, 428-429.

- John Cosin, The History of Popish Transubstantiation, 1840, 54.

- Tyndale, The Complete Works of William Tyndale, 141.

- Richard Hooker, The Word Made Flesh for Us: A Treatise on Christology & the Sacraments from Hooker’s Laws, ed. Brad Littlejohn, Patrick Timmis, and Brian Marr (The Davenant Press, 2024), 108.

- Lancelot Andrewes, Before the King’s Majesty: Lancelot Andrewes and His Writings, ed. Raymond Chapman (Canterbury Press, 2008), 59.

- John Jewel, An Apology of the Church of England, ed. Robin Harris and Andre Gazal (The Davenant Press, 2020), 28.

- Bray and Keane, The 1662 Book of Common Prayer: International Edition, 270.

- Vermigli, The Oxford Treatise and Disputation on the Eucharist, 15, 78, & 113.

- “The Real Presence and Spiritual, by Jeremy Taylor,” n.d., https://anglicanhistory.org/taylor/real/01.html.

- Nicholas Ridley, A Brief Declaration of the Lord’s Supper (New Whitchurch Press, 2021), 15.

- Cranmer, The True & Catholic Doctrine of the Lord’s Supper, 11.

- Hooker, The Word Made Flesh for Us: A Treatise on Christology & the Sacraments from Hooker’s Laws, 42.

- Ibid, 45.

- “The Real Presence and Spiritual, by Jeremy Taylor,” n.d., https://anglicanhistory.org/taylor/real/01.html

- Cosin, The History of Popish Transubstantiation, 11.

- Hooker, The Word Made Flesh for Us: A Treatise on Christology & the Sacraments from Hooker’s Laws, 66 & 113-114.

'This Thy Table: The Anglican Doctrine of the Lord’s Supper' have 6 comments

October 18, 2024 @ 1:54 pm Bennett Ellison

Thanks for this, Jeremy. I love all the variety of sources you pulled on. As you show and summarize well, it is most assured that Christ is present with us in the Eucharist. Where we often associate ‘withness’ with physical proximity detected by our senses, you show well that we Anglicans affirm Christ’s withness unto us really and truly through spiritual union. Good stuff!

For anyone interested in more on this, there is an Anglican conference coming up in February which is on Anglican beliefs on the Eucharist. Located in Savannah, Ga.

https://anglicanway.org/2025-conference/

October 18, 2024 @ 9:27 pm Jeremy Goodwin

Thank you so much for the praise. I will actually be at the conference. My wife and in-laws bought me a ticket already. Hopefully I’ll see you there.

November 23, 2024 @ 11:36 am Ethan Davis

A well-founded and thoughtful article, Jeremy. Thanks for taking the time to craft it! I wonder what you think of the Lutheran rebuttal to the denial of physical presence that goes something like this: Resurrected Jesuses do with their bodies what they like. In other words, why assume that Christ’s body must be tied to particular place? If Christ’s body can be brought back to life and can appear and disappear as it pleases him, why think it can’t be tied to the elements of communion?

November 23, 2024 @ 12:44 pm Jeremy Goodwin

The exegetical argument for the Lutheran claim that Christ’s resurrected body can be ubiquitous with his divine omni-presence is one I’ve never found the least bit convincing. It is one thing that Jesus is shown per the omnipotence of God to translocate or simply obscure himself from human vision such as Luke 24:31 neither of which contradicts the nature of a human body (folding space-time, or bending of light around an object as speculations), as it does not in Acts 8:39-40 when Philip is transported by the Holy Ghost. However, it is important to note that it is purely supposition as to exactly what occured to the resurrected Jesus or to Philip at the act of the Spirit. Another ‘trusim’ is of Christ’s physical body phasing through walls in John 20:19 & 26; neither of which actually say this or offer any explanation as to how Jesus came to be in the room. It is again, pure speculation and supposition that his entry had anything at all to do with the properties of his resurrected body. Now, what reasons do we have to doubt that Christ is simply translocating from heaven to earth in a substantial way to be “in, with, and under” the elements of bread and wine? Well first it would require ubiquity due to the many simultaneous Suppers globally, which we have no reason to assert exegetically and which has us violating what we know of bodies. Secondly it appears to contradict Matthew 26:11 and Acts 1:9-11. It seems to be at odds at least implicitly with Acts 7:55-56 and John 16:7. Thirdly, for Christ to be here with us in a substantial (think Aristotle ei. Form+matter) way, or material or physical manner is inconsistent with the descriptions of his second coming such as Thessalonians 4:16-17 or Matthew 24:44. The typical rebuttal that his coming to be “on the altar” substantially or “in or under” the bread and wine in like manner is all together of a different sort than the second coming so it isn’t contradictory just doesn’t move me.

November 23, 2024 @ 4:19 pm Ethan Davis

Amazing, thanks! I am sympathetic to the Lutheran disposition when it comes to theology, namely, that we are not very capable of grasping divine truths that have not been revealed to us. Generally, that means maintaining some distance on firm assertions of the divine nature that aren\’t closely tied to scripture. I have a decidedly low anthropology. However, I do think that the \”plain meaning doctrine\” that Lutherans sometimes use isn\’t quite fair either because so much enrichment must happen for systematic theology to get off the ground, and reason (with humility) is one of the ways that enrichment happens. So, I vacillate between the sound logic of an Anglican position and the humility of a Lutheran one.

November 23, 2024 @ 4:51 pm Jeremy Goodwin

I often hear the claim that Reformed view is “logic chopping” and the Lutheran view is “mysterious” and thus lends itself to humility more. However, I take issue with the claims. The Divines defended the Reformed view is a recovering from the patristics: basing the teaching off Tertullian, Origen, Augustine, and many other besides all the way through the middle ages with Arnoldus, Hus, and Wycliffe. As for humility it was largely based on actually maintaining mystery. Vermigli refused to multiple miracles unnecessarily because that placed demands upon God which were not associated in any way with the divine revelation of Himself and His work. Cranmer saw it as flying in the face of reason, yes, but also not taking Christ to be where he promised to be until he came again, that is in heaven. Lancelot Andrewes saw this mystical union with Christ as preserving divine mystery by plumbing no further than the scriptural fact that Christ annexed a promise unto His Supper. Richard Hooker said that the exact way in which Christ gave us Himself by way of a Sign was truly mysterious and we need not venture further than to believe the promise that by eating the bread our souls and bodies were nourished to eternal life by union with Christ. To me the Reformed view is reasonable but also mystical and humble.