“As long as we remain divided, we grieve the Spirit of Jesus.”

~Peter Leithart, The End of Protestantism[1]

The Church needs help. Low church Protestantism is not working. It is too commercial, too disassociated with the broader tradition of the church, and too isolated from other Christians. This line of criticism is a well-worn cliche. Unfortunately, the main alternative is not much better. In the West especially, Roman Catholicism is not working. Not only do all the same historical and theological criticisms of the Roman Catholic Church taken up by the Reformers still stand today, but in recent decades, Rome has proven itself to be just as susceptible to the erosion of liberalism as any form of Protestantism. In fact, everyone across the board seems to be eager to compromise with unbiblical sexual ethics, gender politics, and all manner of unfaithfulness these days. Even the megachurches are joining in.

Between charismatic strangeness, liberal apostasy, and a general depression in the Body especially regarding the drive for personal holiness, the Church is in trouble. The Bride is sick. She has forgotten the Word of God. She has forgotten her traditions. Her people are confused. They don’t pray. They don’t know their Bibles. They don’t pass the faith on to their children.

Interesting Times and the Ad Fontes Call

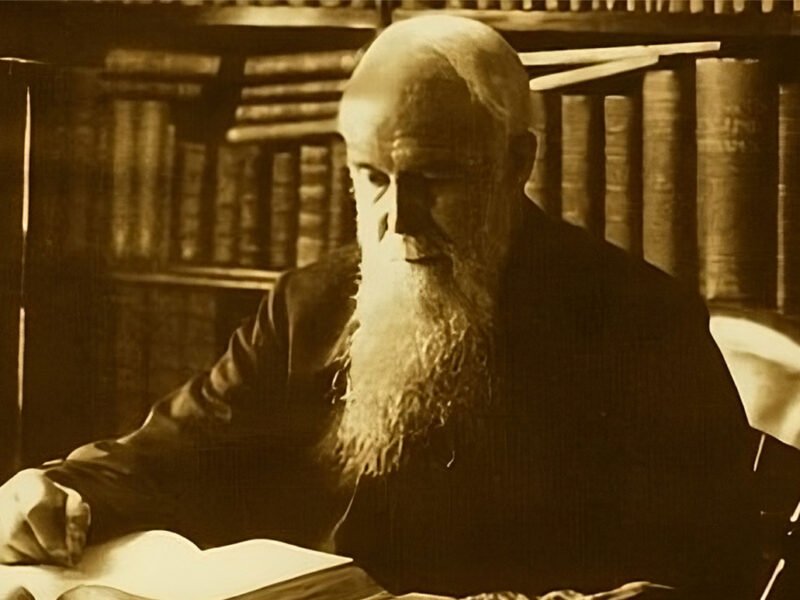

I believe we are approaching the dawn of the next great reform of the Church. Our higher-ups have lost the plot, no matter what ecclesial community you call home. The Church needs a reset. Everyone is feeling it. Schisms are constantly cropping up. Scandals are frequent. We need help. In our Anglican neck of the woods, this desire for renewal often takes the form of spaces like this wonderful journal. The Body is suffering from chaotic amnesia. Who are we? What are we for? Many in our tradition have imbibed the chaotic relativism that characterizes our time and desperately insisted that it’s the Gospel. What can we do about this? The North American Anglican answers that question by rightly pointing to the original sources. Ad fontes! Take and read your ancestors’ treasure! This wonderful forum has connected me to many spiritual and theological resources across time and space. I have found a special companionship with the English Reformation, the spiritual treasures of the Caroline Divines, and great men of the faith across the spectrum of Anglicanism like Charles Simeon, John Keble, and John Wesley. I have resolved much of the ecclesial anxiety characteristic of my early walk with Christ through the Reformational and catholic character of Anglicanism. Most importantly, The North American Anglican and spaces like it turned me on personally to many currently living bastions of hope and clarity in a world of confusion, people who have become real-life friends.

But I would be concealing something major in my own heart if I said that projects like this one and others like Anglican Compass are an end to themselves. Many in the Anglican Communion are concerned with maintaining faithfulness to our own Anglican patrimony, heritage, and above all to the Scriptures themselves. I certainly count myself as one of these people. I love to pray with Andrewes, read with Ryle, and sing with Wesley. However, as I enter into the conversation of this tradition, I am increasingly convinced that what we do as orthodox Anglicans creates ripples out into church history far beyond what many of us think about on a regular basis in our parishes and dioceses. What is the point of what we are doing here?

Anglican Influence in the Broader Scope

The more I ponder this and read deeper into our heritage, I think many of us have too short-sighted a vision of what our tradition really means. What does it mean to be a Global Anglican in our time? Does it simply mean to return to a certain golden age of Anglican practice? Does it mean to stand up to the progressive mutations of the Gospel in our day? I think it’s more than this. What happens to GAFCON and the broader orthodox Anglican is important not just for those of us who love the Prayer Book, the Formularies, and the wonderful tradition of the English Reformation. Beyond this, the success of the orthodox Anglican movement speaks to the viability of a truly catholic, and truly reformed global tradition. Our movement is not just about maintaining orthodoxy on sexuality in yet another denomination. That is a fight that everyone seems to be fighting right now, including the Roman Catholics who have been historically more immune to talks of schism and division over doctrine and ethics.

The fruits of our labor in the Anglican movement have eschatological implications. Anglicanism has always been going somewhere. There is a good reason this work must be continued even as we stabilize after our recent liberal/conservative schism. Church history is a mess, especially in the last 500 years. The Reformation restored much but there was a high cost. And those of us on this side of the Tiber have mostly lost the mission of Calvin, Cranmer, and Luther, none of whom ever wanted division for the sake of division. As Dr. Leithart reminds us, whenever God divides, it is always for a greater unity.[2] The divisions of light and dark, male and female, plant and animal, even the divisions of the tribes of Israel, are all for the sake of a greater good. This was the intention of our Reformers but most of us Protestants have forgotten our mission. Instead, we downplay the scandal of division. But if we believe in the Gospel, that God has predestined a particular people, to be His own, if we believe the words of our Lord Jesus in John 17, if we believe, along with Calvin and Cyprian that no one can have God as our Father without the Church as our Mother, then we ought to be much more concerned that the visible Church, our discernible Mother, is not easily identifiable for the average Christian.

The Need for Clarity in Ecclesiology

Where is the Church? Augustine, Bernard, and Aquinas would have told you. Luther, Calvin, and Cranmer would have told you. But today, we use language that is far too speculative and flimsy to describe the Church or we end up using a definition so doctrinally tight that it unchurches many obvious disciples of Jesus. We’ve lost our ability to speak clearly as the Church[3]. The Church needs synthesis. The Bride needs fewer heads.

Our Anglican liturgy, our various statements on Anglican identity especially the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral, and the global communion of orthodox Anglicans itself represent a few clues about the future of the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church. As I live and pray into this wonderful, though often confusing communion, I’m convinced that the pain and confusion of it is the pain and confusion of the Body of Christ. It is particularly acute for Anglicans because unlike some, we have the courage to admit that Christendom post-1517 is truly confusing. It needs some parsing out.

Because of the current confusion, our future simply cannot be about collapsing all right-believing Christians into one particular currently existing communion or confession, but involves doing the difficult work of letting go of precious shibboleths and figuring out how to make sense of it all. The Quadrilateral does this well. The stakes are higher than Canterbury, Rome, or Geneva. There is more than temporary peace at stake. That’s something our Reformers wrought for us but we were never meant to stay there. There are theological and ecclesial cliffhangers that need to be resolved. Modern commentators like Leithart, Robert Jenson, and Archbishop Michael Ramsey have all pointed us to this. Our current division existentially threatens our mission and robs our preaching and our sacraments of their meaning. Something must change. Yet, the Church doesn’t have a clear answer to this problem. Whatever visible unity that is possible for the future is only available to us today in embryonic form. The answer to our division has yet to be revealed by God. So where are the seeds He has planted?

Seeds of Unity in Anglicanism

I believe our Global Anglican Communion and the spiritual riches of the Prayer Book are two such seeds. The project of Anglicanism is essentially about maintaining reformational doctrine within a catholic structure. We, as Anglicans, can say to both our brothers in Rome and our brothers in the tent revivals, you are truly our brothers but you have all made a few mistakes and so have we. Our ecclesiology is both strangely high and catholic while remaining low and humble about its own ecumenical status. We can, like Bp. Ramsey, insist on Episcopacy without unchurching everyone who isn’t us.[4] We can affirm the Sola’s as the Reformers envisioned them and not as a crude slogan that diminishes the proper place of tradition and canonical reading. Because of the tumultuous and sometimes, frankly, confused theological trajectory of our tradition, we alone can both avoid ecclesial triumphalism and wicked pluralism. The old questions we as Anglicans have constantly wrestled with: are we catholic or Protestant? Are we Reformed or Lutheran? How liberal is too far? What are the majors and minors of orthodoxy? How can we make room for everyone while keeping out the wolves and heretics? How do we order the Church in light of unfaithful shepherds and the clear witness of our forebears? From where is authority derived in the Church? How ought we to worship and read Scripture together? These questions which we are constantly rehashing and arguing over on blogs and journals like this one, they’re the same questions the entire Church has been asking Herself since the Reformation, and they are central to the Anglican story in a fundamentally different way than other Protestant traditions. The conversation of Anglicanism is the conversation of the catholic church from 1517 onward. Our tradition looks back to the Fathers, it takes in Reformers but it also looks forward to the end of Protestantism: a reunited, single, visible, and apostolic communion of Christians who can embrace both the great tradition, the ancient liturgy, and the sacramental worldview of the Church as well as the unsupplemented, undistorted, and unrivaled Word of God.

An important mentor of mine recently reminded me that this unity that I long for in the Church, is a gift already bestowed upon the Bride.[5] Everything we have: our faith, our sanctification, our union with Christ, our Baptisms, they are all pure gifts. What do we have that we did not receive? What can we hope for in the future that won’t be a gift? Ultimately, more than any program we can devise or dialogue we can organize, the hope of the Church lies first in God’s prevenient grace. We know we will eventually become visibly one again because the Father always answers the Son’s prayer. So then, as I ponder the telos of our movement, I can only open wide my hands again to the One who has given me everything I have, who has given me even Himself. What a gift our tradition is! Our Prayer Book is the only liturgy officially authorized by Christians in Protestant, Roman, and Eastern Communions. Our liturgies proclaim the wonderful gospel cry of the Reformation clearly and beautifully. The Quadrilateral is, in my estimation, the most feasible and faithful vision for ecumenical Christianity. And these are not just two ecumenical statements of faith worked up by a committee somewhere that was quickly forgotten about. No, our tradition is alive and beautiful. There are millions of Christians across many tribes and tongues praying the Prayer Book as you read this. And they share a visible communion in line with the principles of the Quadrilateral.

So in my sadness over the church’s division and in my deeper discovery of the treasures of our Anglican heritage, I am consoled. I have been given a gift. Gifts must be stewarded, of course, and the Giver does expect a return on His investment one day (Matthew 25:14-30) but gifts are also to be enjoyed. I thank God for Anglicanism and its work toward a true Reformational Catholicism. God is working out His purposes, even among our chaotic and seemingly hopeless confusion. If God was going to bring the Church back together today, I think it would look a lot like what I already do every morning and evening in my personal prayer and every Sunday with my little portion of His Body which He has graciously shared with me.

Notes

- Peter J. Leithart, The End of Protestantism : Pursuing Unity in a Fragmented Church. (Grand Rapids, Michigan, Brazos Press, 2016), p. 1 ↑

- Peter J. Leithart, “Division and Reunion,” Patheos (2005) ↑

- James R. Wood, “Can The Church Still Speak?” Comment (2023) ↑

- Michael Ramsey, The Gospel and the Catholic Church (London, New York, Longmans, Green and Co., 1936), 189-192 ↑

- Rev. Dr. Jonathan Bailes, The Givenness of Ministry, Beeson Chapel Sermon ↑

'The Gift of Unity' have 4 comments

April 24, 2024 @ 11:21 am The Reverend Robert Placer

The major obstacle to unity within the global Anglican Church is impaired communion resulting from the unscriptural sectarian ahistorical ordination of women to holy orders along with the related ordination of homosexuals, lesbians, and transsexuals. If we value such unity within the global Anglican Communion before pursuing even greater unity within the Protestant Church then the aforementioned deviations from biblical and catholic doctrine on holy orders must be renounced. Refusing such renouncement means rejecting unity. The vast majority of global Christians reject women’s ordination along with the ordination of the other sexual deviants. I doubt that the desire for unity will overcome these idols of the heart.

April 24, 2024 @ 1:27 pm Christian Cate

Regrettably, the author’s failure to mention the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Coptic Church in this discussion renders the whole article disingenuous.

Since the author is a smart man, one could reasonably conclude that this omission was deliberate, and not accidental or incidental.

The issue of Christian Division and return to the sources (Ad Fontes) cannot be reasonably addressed without reference to the Church Fathers and the Eastern tradition. Please do an update / revision of this article pulling in these resources as well to make the article truly comprehensive and more effective.

April 24, 2024 @ 1:37 pm Christian Cate

Oh, there it is. A tiny reference to the Eastern Communions. My apologies. Nevertheless, the name Orthodox is vital to the discussion. It implies a set of important beliefs that are necessary to this discussion. Those beliefs can be “reverse engineered” to help Anglicanism, IMHO. Folding everyone into one Communion is not possible. Yet. Never say never, though. Perhaps it depends on how hard everyone is willing to work on it.

April 24, 2024 @ 11:15 pm Sudduth Rea Cummings

Interesting article and it merits thought. I find it curious that my family’s church while I was growing up as the Christian Church/Disciples of Christ which was started as an American 19th century church unity movement wound up dividing three ways: the fundamentalist Church of Christ, the conservative Christian Church (not Disciples), and the liberal Disciples of Christ. I entered the Episcopal Church as a freshman in college after a conversion experience in St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Enid, OK, and in retirement when the Anglican Church in North America was founded, I entered it happily. My fellow General Theological Seminary grad, Robert Duncan, was the first Archbishop of ACNA. And I’m glad that there is a faithful, orthodox alternative in GAFCON to the Anglican Communion.