In the tradition of Celtic breastplate prayers, St. Patrick’s Breastplate, or “The Deer’s Cry,” is the most famous. These longform prayers run down the particulars of the human person, body and soul—at times in graphic detail—and implore God’s protection on that member and its commission to God’s purposes. The effect is we become his full possession yet fully embedded in his creation.

These breastplate prayers, including St. Patrick’s, arose from monastic reflection on Paul’s description of the armor of God in Ephesians 6.[1] It seems fruitful then to use the latter to exegete the former, to the end of showing that prayer with and for the body is integral to the Christian spiritual life, as what the body does is the very work of the soul.

The image of the soul

This immediately brings up the question, how exactly are the body and soul integrated such that we can call bodily actions “the work of the soul”? A brief answer to this question comes from John Scotus Eriugena, a ninth-century Christian in Ireland: just as “the soul is the image of God,” so “the body is the image of the soul.”[2] In other words, if we want to know what a soul is doing or what it looks like, we look at the body. Is this not a part of what Jesus means when he says, “If you have seen me, you have seen the Father” (John 14:9)? Jesus is the truest bodily Image of God, so the way to see the invisible, ineffable God is to look into the face of Christ.[3] In the same way, Eriugena argues, if we want to know what a soul “looks like,” we need only look at that soul’s body.

We can also address this in a more indirect way by following Paul’s discussion of baptism in Romans 6. He discusses the sacrament as something that happens to the body which affects our souls. The immersion of our bodies in water, according to Paul, is the means by which our souls die with Christ and are subsequently raised with him (Rom 6:3–5). This seems to point to a close integration of the soul with the body such that the things that are done in the one affect the other. Therefore, Paul concludes that our bodies should no longer be subject to sin: “Do not present your members”—that is, each part of your bodies—“to sin as instruments of unrighteousness, but present … your members to God as instruments of righteousness” (vv. 12–13). Paul expects that the actions of one’s body ought to follow from the state and will of one’s soul, but that very state is also initially affected by the immersion of the body.

Later, in Romans 8, Paul speaks dichotomously of living “according to the flesh” and “according to the Spirit” (Rom 8:4–9). At first, it seems that Paul’s goal is to get us out of the body and into the spiritual world. He even says that “those who are in the flesh cannot please God” (v. 8). But he then goes on to say, “If the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised Christ Jesus from the dead will also give life to your mortal bodies through his Spirit who dwells in you” (v 11; emphasis mine).

When Paul talks of “the flesh,” then, he cannot be referring to the physical body. Drawing from Celtic Christian and Kabbalistic Jewish theology, J. Philip Newell argues,

When St. Paul teaches that we are to live “according to the spirit” rather than “according to the flesh,” he is not suggesting that we should not live according to the body. It is precisely in our bodies that we are to live according to the spirit, rather than allowing ourselves, including our bodies, to be dictated to by what is opposed to our inmost being.[4]

That is, the sin that causes the body to be spiritually dead flesh.

A breastplate of prayer

If actions of the body are the work of the soul, the body becomes an integral part of the Christian life. This is one of Paul’s assumptions as he writes to the Ephesians. Paul spends the first half of his letter casting a vision of how God has “broken down in his flesh the dividing wall of hostility” between different peoples and made one body which is indwelt by one Spirit through one baptism uniting each person to one hope and faith in one God and Father of all (Eph. 4:4–5). Notice that the image of unity here is a human body. The rest of his letter is spent detailing what it looks like to “walk in a manner worthy of the calling to which you have been called” (v. 1). That is, given that there are no spiritual walls of hostility between souls in the church, these are the appropriate bodily actions for that sort of soul: not speaking falsehood but truth (v. 25); not stealing but being generous with the things God has given (v. 28); not being drunk but singing praise and practicing gratitude (5:18–20). Further, he describes how Christians ought to order relationships with one another by what they do with their bodies (5:21–6:9). This way of life he purports to be oriented toward the goal of imitating God by imitating the love which Christ demonstrates in his own bodily action (see 5:1–2).

All this leads to an admonition to “Finally be strong in the Lord and in the strength of his might. Put on the whole armor of God” (Eph. 6:10). Clinton E. Arnold argues that in this final portion of his letter, Paul is warning the Ephesians that there are powerful spiritual forces at work in the world that will make following God in the aforementioned ways very difficult. In fact, the union with each other and with God in the church is meant to hold firm against such spiritual opposition.[5] This passage also alludes to Isaiah 59 when, in the face of injustice, God himself “put on righteousness as a breastplate, and a helmet of salvation on his head” (Isa. 59:14–17).[6] And yet Paul admonishes us to put on God’s armor, which includes the same “breastplate of righteousness” and “helmet of salvation” (Eph. 6:14, 17). This clearly seems to be something that happens spiritually and invisibly; Christians do not generally go around wearing breastplates and helmets. Praying with the armor of God in mind is often termed “spiritual warfare.” So, what has it to do with the body?

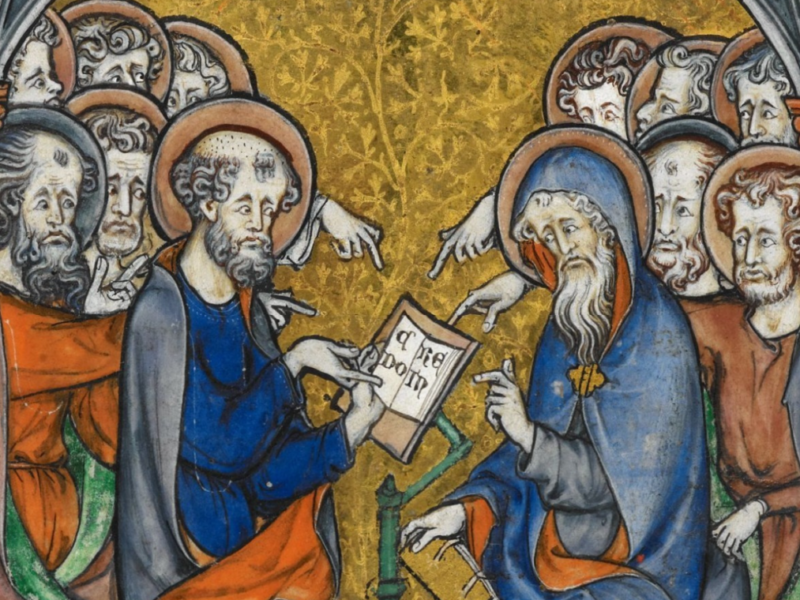

In the Celtic Christian tradition, a series of loricae, or “breastplate prayers” like the one attributed to St. Patrick, became a popular style in Ireland and Britain. This style involved praying over the body and all aspects of life. The breastplate style, which originated as early as the fifth century in the monastic application of Ephesians 6:11–18, seems to be intended for use in the morning upon waking.[7] These prayers began showing up in prayer books by the late eighth century. Oliver Davies, a historian who has written extensively on Celtic and Welsh Christianity, comments, “The intention of these devotional songs is often to consecrate the whole of human life.”[8] The armor of God surrounding the one praying was the necessary bodily protection by which one could go about one’s day following the triune God, including both prayer and acts of charity. Even if “we do not wrestle against flesh and blood,” we still fight with (i.e., use) our bodies in prayer. The armor, then, is prayer, “at all times in the Spirit” (Eph. 6:18). The following examples of Celtic prayer demonstrate this connection between prayer for the body and the body’s work in the world.

The Breastplate of Laidcenn can be dated to before AD 661, when Laidcenn of Clonfert died.[9] It begins with a cry for help from the triune God. Much like the Hebrew Psalms, Laidcenn describes himself to be “as if in peril on the great sea” (cf. Ps. 69:1–3). But the most remarkable thing about this prayer is not only the list of all the heavenly and earthly powers, the whole company of heaven, but also the comprehensive list of the parts of the body—possibly every part Laidcenn could think of—that may need divine protection and upholding. Laidcenn is desperate for comprehensive divine protection, “[s]o the foul demons shall not hurl their darts into my side, as is their wont.”[10] This hearkens back to Ephesians 6:16: “In all circumstances take up the shield of faith, with which you can extinguish all the flaming darts of the evil one.” Though demonic forces are spiritual, Laidcenn follows Paul in understanding that their schemes can cause havoc in the physical world.

It may be pointed out that the prayer ends “So that leaving the flesh I may escape the depths, and be able to fly to the heights, and by the mercy of God be borne with joy to be made new in his kingdom on high. Amen.”[11] Although this may seem to lend itself toward a denial of the importance of the body, the rest of the prayer shows that Laidcenn clearly thinks of the body as important. The context of the prayer suggests that Laidcenn actually desires a lengthening of life, until he grows old. In fact, the benefit of growing old is that he would have an opportunity to further “expunge [his] sins with good deeds.”[12] Admittedly, to the popular Protestant mind, this immediately smacks of works-righteousness. While Laidcenn may have unfortunately been influenced theologically by the earlier British theologian Pelagius, there is a danger of missing Laidcenn’s heart: His goal in this prayer is that by the protection of his body, he may have greater opportunity while on earth to do the will of God.

Much more well known, and arguably more orthodox, than Laidcenn’s prayer is St. Patrick’s Breastplate.[13] Traditionally, this prayer is prayed upon waking as preparation for the day ahead—six times a new set of petitions begins with “I rise today …”[14] Like Laidcenn, Patrick begins by invoking the triune God himself, followed closely by the whole company of heaven, the saints, and the forces of creation, from the highest to the lowest. In each set of petitions, the rhythm of each line wraps the petitioner layer by layer in the power of God and those who are for him. So enfolded, Patrick names the enemies that may harm “the body and soul,” both malicious and accidental, “so that I may have abundant reward.”[15] This reward is the climax petition:

Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me;

Christ within me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me;

Christ to right of me, Christ to left of me;

Christ in my lying, Christ in my sitting, Christ in my rising;

Christ in the heart of all who think of me,

Christ on the tongue of all who speak to me,

Christ in the eye of all who see me,

Christ in the ear of all who hear me.

This glorious section shows that it is not actually this prayer that is the breastplate: Christ himself is our divine armor! It is Christ who surrounds and protects the petitioner. So, Paul says, “For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ” (Gal. 3:27; emphasis mine). We put on Christ as our armor so that “[s]in will have no dominion over” us (Rom. 6:14). But Patrick goes further: Not only is Christ to cover our bodies like armor, but he ought to be found in those we minister to, that is to say, in paraphrase, “May Christ be so deeply ingrained in my body that all those who know me know Christ.” Thus the fulfillment of John Scotus Eriugena’s claim: If our souls are truly the image of God—if we are conformed to Christ, the true Image, and if he dwells this deeply in us—then our bodies will be the images of those Christ-shaped souls.

The evangelization of the body

If the body matters this much to our spirituality, as the Celtic prayer tradition highlights, then the healing and protection of the body can and should be a part of our daily prayer in the church and part of our evangelistic ministry. This latter is what Jesus, the apostles, and countless others throughout the history of the church have done to draw people to the kingdom of God. There is a pattern where, when the body is healed by the power of the Holy Spirit, the soul is drawn with the body into the healing power of the gospel (e.g., John 9:1–41; Acts 3:1–10; Jas. 5:13–18).

Jesus claims that his ministry, anointed by the Spirit, is precisely one of “proclaim[ing] good news to the poor, … liberty to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, [setting] at liberty those who are oppressed [and proclaiming] the year of the Lord’s favor” (Luke 4:18–19; cf. Isa. 61:1–2). All of these actions require a body of, at the minimum, those who receive this ministry.

Each of Jesus’ instructions in the Great Commission must be done by embodied souls: baptizing, discipling, teaching (Matt. 28:19). Prayer for our bodies and for the bodies of others in ministry is expected and integral in the Christian life. This does not mean that all Christian’s bodies will be healed and protected from every malady or danger in this life: Some sufferings are for our own growth.[16] And God’s providence remains a mystery. Even so, we should expect that even in this life the gospel will not only touch our souls, but that our bodies will need evangelization as well, that we might be healed entirely. Which is to say, God’s own entirely.

Notes

- Oliver Davies and Thomas O’Loughlin, eds. and trans., Celtic Spirituality, The Classics of Western Spirituality (Paulist Press, 1999), 46. ↑

- John Scotus Eriugena, Periphhyseon (The Division of Nature), quoted in J. Philip Newell, Echo of the Soul: The Sacredness of the Human Body (Morehouse Publishing, 2000), xi. ↑

- It should be clarified here that this says nothing about the relation between Persons of the Trinity, but that, in the relationship between the Incarnate Christ and the Godhead, the invisible is perceived in what is visible. ↑

- Newell, Echo of the Soul, xiii. Cf. Rom 8:10. ↑

- For this discussion, see Clinton E. Arnold, ed., Ephesians, Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament 10 (Zondervan, 2010), 435–37. ↑

- I am grateful to Bishop Stewart E. Ruch III for pointing out this connection in a sermon preached on November 24, 2024. ↑

- Davies and O’Loughlin, Celtic Spirituality, 46. ↑

- Davies and O’Loughlin, Celtic Spirituality, 46. ↑

- Davies and O’Loughlin, Celtic Spirituality, 46. For the sake of discussion, I will assume the attribution of authorship to be authentic. ↑

- “The Breastplate of Laidcenn,” in Davies and O’Loughlin, Celtic Spirituality, 292. ↑

- “Breastplate of Laidcenn,” 290. ↑

- “Breastplate of Laidcenn,” 292. ↑

- John Bagnell Bury makes a strong argument for the Patrician authorship, which would date the prayer to the fifth century. See John B. Bury, The Life of St. Patrick and His Place in History (Cambridge University Press, 2019), 246. ↑

- “Patrick’s Breastplate,” in Davies and O’Loughlin, Celtic Spirituality, 118–20. ↑

- “Patrick’s Breastplate,” 119–20. ↑

- For an excellent treatment of the importance of praying for bodily healing alongside a recognition that suffering will be a part of a Christian’s life in this world, see Francis MacNutt, Healing (Ave Maria Press, 1999), 49–70. ↑