Introduction

In the history of the sacramental practice of the Church, the order of receiving the Eucharist and Confirmation has been a subject of theological reflection and liturgical variation. Traditionally, the sacrament of Confirmation has been administered before one’s first reception of the Eucharist, serving as a completion of Baptismal grace and a preparation for full participation in the Eucharistic feast. However, there are compelling theological arguments that support the reception of the Eucharist prior to Confirmation, aligning with the divine order of spiritual growth and the flexible sacramental economy articulated by some Church Fathers.

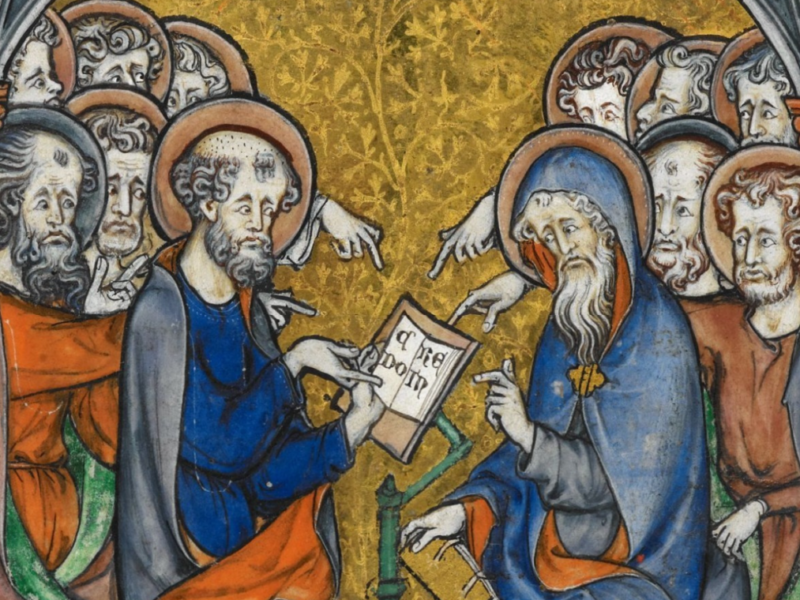

Drawing upon the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius in his “Ecclesiastical Hierarchy” and from St. Thomas Aquinas in his Summa, this article seeks to explore and justify the theological underpinnings of this practice. By examining the hierarchical stages of purification, illumination, and perfection, we find a framework that not only accommodates but indeed supports the reception of the Eucharist before Confirmation. Additionally, I will examine an order of it as presented in the scriptures. This approach seeks to emphasize the Eucharist as an essential source of spiritual nourishment and enlightenment, preparing the regenerate for the subsequent completion and empowerment received in Confirmation.

Through a nuanced understanding of the sacraments and their interrelated roles in the life of the believer, we can appreciate the theological flexibility that allows for varying sequences. Ultimately, this exploration aims to demonstrate that receiving the Eucharist prior to Confirmation is not only acceptable but can be seen as a profound means of aligning with the divine economy and fostering deeper spiritual growth and union with God while also practicing paedocommunion.

The History of American Anglican Practice

The history of Anglicanism in North America can be traced back to the late 16th century, specifically to the voyages of English explorers. In 1579, Sir Francis Drake, during his circumnavigation of the globe, landed near what is now San Francisco Bay. There, he and his crew conducted a Communion service, marking the first recorded Anglican worship on the continent. Further attempts at colonization, such as Sir Walter Raleigh’s 1589 expedition to present-day North Carolina, likely included Anglican worship practices. However, it was not until the establishment of the Virginia Colony in 1607 that Anglican parishes were systematically founded. In Virginia, each county was outfitted with essential institutions, including a church, a minister, a vestry, magistrates, and a courthouse, all supported by public funds. This tradition of local governance played a significant role in shaping the founders of the American Republic as they developed the framework for a new nation.

The expansion of Anglicanism in the American colonies predominantly followed a south-to-north trajectory. After its robust establishment in Virginia, Anglicanism spread under the reign of Charles II (1660‒85) to Maryland and into several counties of New York. By the latter part of the 17th century, Anglican parishes began to appear in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Jersey. In Rhode Island, where there was no entrenched Puritan establishment, Anglicanism found an early and more welcoming environment. Nevertheless, the Church remained relatively weak in New England, relying heavily on the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, an organization founded in 1697 to bolster its efforts.

A significant impediment to the Church of England’s growth in the colonies was the lack of an episcopal presence. Puritan New Englanders and Whigs in England repeatedly blocked proposals to appoint a colonial bishop, first during Queen Anne’s reign (1702‒14) and later under George III in the 1760s. To address this deficiency, the Bishops of London appointed “Commissaries” to perform non-sacramental episcopal duties in the colonies. This stopgap measure offered some relief, but aspiring clergy were still required to travel to England for ordination, a perilous journey that claimed the lives of about 10% of those who attempted it. Consequently, confirmation was not practiced in the Colonial Church; individuals were admitted to communion once they had learned the catechism and were considered “ready and desirous” of confirmation by their minister. It wasn’t until the Lord blessed us with his grace Samuel Seabury, to build Christ’s church in America. It is on this background we should understand the ordering of the sacraments in situations like this.

St. Thomas Aquinas on the Order of the Sacraments

St. Thomas Aquinas argues that the sacraments were instituted for a twofold purpose: to perfect man in things pertaining to the worship of God and to remedy the defects caused by sin. Just as human life is perfected through various stages—birth, growth, nourishment, and healing—so too is the spiritual life perfected through the sacraments, each addressing different aspects of our spiritual journey.

Aquinas outlines a natural and logical order among the sacraments. Baptism, as the sacrament of spiritual birth, naturally comes first, initiating the individual into the Christian life. Confirmation follows, strengthening the baptized with the gifts of the Holy Spirit, much like growth fortifies the body. The Eucharist, which nourishes the soul with the body and blood of Christ, is essential for sustaining spiritual life.

Penance and Extreme Unction are sacraments of healing, addressing spiritual infirmities that arise after Baptism. Order and Matrimony, while serving the community and the Church’s continuity, follow the personal sacraments, as they pertain to the communal and social dimensions of human life. Among the sacraments, the Eucharist holds a place of preeminence. Aquinas asserts that the Eucharist is the greatest of all sacraments because it contains Christ Himself substantially. While other sacraments confer grace and mark significant stages of spiritual development, the Eucharist is the summit, offering the actual presence of Christ and thus the ultimate nourishment for the soul.

Eucharist Before Confirmation

Trying to work from a primarily Thomistic framework, the argument for administering the Eucharist before Confirmation finds theological justification. Aquinas explains that spiritual life mirrors physical life: just as nourishment is necessary for physical growth, so is the Eucharist essential for spiritual vitality. Confirmation, which strengthens the baptized, can logically follow the Eucharist if we consider the immediate need for spiritual sustenance. By receiving the Eucharist, children partake in the life-giving body and blood of Christ, which can support their spiritual growth until they receive the fortifying grace of Confirmation.

One might object that the traditional order—Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist—should be rigidly maintained. However, as Aquinas suggests, the sacraments, while ideally following a particular order, are ultimately flexible in their application, provided the underlying spiritual needs are met. The Eucharist’s role as spiritual nourishment can precede the strengthening of Confirmation without undermining the integrity of the sacramental order. The centrality of the Eucharist and the appropriate ordering of the sacraments play crucial roles in this structure, particularly concerning the sacrament of Confirmation and its relationship to the Eucharist.

The Central Role of the Eucharist in Sacramental Theology

In his Summa Theologica, Aquinas articulates a clear and deliberate order among the sacraments, reflecting their purposes and effects on the believer’s spiritual journey. This order underscores the progression from initiation to the culmination of spiritual life. Baptism, as the first sacrament, signifies spiritual rebirth and incorporation into the Church. Following Baptism is Confirmation, which imparts the Holy Spirit, granting strength and fortitude to the baptized. The Eucharist, then, is the pinnacle, where believers partake of Christ Himself, sustaining and perfecting their spiritual life.

Aquinas addresses the order of these sacraments in Article 2, replying to Objection 3. It reads:

Article 2. Whether the order of the sacraments, as given above, is becoming?

Objection 3: Further, the Eucharist is a spiritual food; while Confirmation is compared to growth. But food causes, and consequently precedes, growth. Therefore the Eucharist precedes Confirmation.

Reply to Objection 3: Nourishment both precedes growth, as its cause; and follows it, as maintaining the perfection of size and power in man. Consequently, the Eucharist *can* be placed before Confirmation, as Dionysius places it (Eccl. Hier. iii, iv), and can be placed after it, as the Master does (iv, 2,8).

He recognizes that nourishment (the Eucharist) both can precede and follows growth (Confirmation). This dual relationship emphasizes the central role of the Eucharist. While it might seem logical that spiritual nourishment should precede spiritual growth—since nourishment typically enables growth—Aquinas places the Eucharist after Confirmation in his order of sacraments. This reflects a theological understanding that Confirmation prepares the faithful to receive the Eucharist with the necessary spiritual maturity and strength.

Flexibility in Sacramental Order

This order, however, does not rigidly prevent the administration of the Eucharist before Confirmation. The Church’s pastoral decisions, reflecting particular contexts and needs, can prioritize the immediate spiritual nourishment that the Eucharist provides. Aquinas’ flexibility in sacramental ordering acknowledges the Eucharist’s unique position as both the end and the means of spiritual growth. As Dionysius notes, and Aquinas reiterates, nearly all sacraments find their culmination in the Eucharist, symbolizing the fullness of ecclesial and spiritual life.

Aquinas’ response to Objection 3 encapsulates this nuanced understanding. He asserts that nourishment can be seen as both preceding and following growth, maintaining that while Confirmation is typically seen as a preparation for the Eucharist, the Eucharist itself is fundamental for spiritual sustenance at any stage. This dynamic relationship reinforces the Eucharist’s centrality, suggesting that receiving the Eucharist can enhance and support the spiritual growth fostered by Confirmation.

Theologically, this approach aligns with the understanding that the Eucharist embodies the source and summit of Christian life. It holds a unique place as the sacrament that directly connects believers with the mystery of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection, thereby sustaining the spiritual vitality necessary for living out the Christian vocation. Thus, while Confirmation fortifies the believer, the Eucharist continuously nourishes and perfects the soul, making it the indispensable heart of the sacramental order.

Psuedo-Dyionisius’ Ecclesiastical Hierarchy:

Below, I will quote most of the third chapter of Ecclesiastical Hierarchy up to the section that Aquinas mentioned for contextual reference of interpretation:

But, inasmuch as the Divine Being is source of sacred order, within which the holy Minds regulate themselves, he, who recurs to the proper view of Nature, will see his proper self in what he was originally, and will acquire this, as the first holy gift, from his recovery to the light. Now he, who has well looked upon his own proper condition with unbiassed eyes, will depart from the gloomy recesses of ignorance, but being imperfect he will not, of his own accord, at once desire the most perfect union and participation of God, but little by little will be carried orderly and reverently through things present to things more forward, and through these to things foremost, and when perfected, to the supremely Divine summit. An illustration of this decorous and sacred order is the modesty of the proselyte, and his prudence in his own affairs in having the sponsor as leader of the way to the Hierarch. The Divine Blessedness receives the man, thus conducted, into communion with Itself, and imparts to him the proper light as a kind of sign, making him godly and sharer of the inheritance of the godly, and sacred ordering; of which things the Hierarch’s seal, given to the proselyte, and the saving enrolment of the priests are a sacred symbol, registering him amongst those who are being saved, and placing in the sacred memorials, beside himself also his sponsor,—-the one indeed, as a true lover of the life-giving way to truth and a companion of a godly guide, and the other, as an unerring conductor of his follower by the Divinely-taught directions.

Quote, Baptism:

But, inasmuch as the Divine Being is source of sacred order, within which the holy Minds regulate themselves, he, who recurs to the proper view of Nature, will see his proper self in what he was originally, and will acquire this, as the first holy gift, from his recovery to the light.

In this section, it is being elucidated that the initial step of the spiritual journey as the recognition of one’s true essence and the return to the divine light. This signifies the purification and enlightenment conferred through Baptism. Baptism is described as the “first holy gift,” guiding an individual out of the darkness of ignorance and into the illuminating embrace of divine wisdom and grace.

Quote, Eucharist:

Now he, who has well looked upon his own proper condition with unbiased eyes, will depart from the gloomy recesses of ignorance, but being imperfect he will not, of his own accord, at once desire the most perfect union and participation of God, but little by little will be carried orderly and reverently through things present to things more forward, and through these to things foremost, and when perfected, to the supremely Divine summit.

Following Baptism, the individual emerges from ignorance and embarks on a gradual ascent of spiritual growth. This journey, undertaken “little by little,” underscores the necessity for continual spiritual nourishment and enlightenment provided by the Eucharist. The Eucharist fortifies the individual, enabling them to progress from the present towards higher spiritual realms, thus fostering their steady advancement towards divine union.

Quote, Confirmation:

An illustration of this decorous and sacred order is the modesty of the proselyte, and his prudence in his own affairs in having the sponsor as leader of the way to the Hierarch. The Divine Blessedness receives the man, thus conducted, into communion with Itself, and imparts to him the proper light as a kind of sign, making him godly and sharer of the inheritance of the godly, and sacred ordering; of which things the Hierarch’s seal, given to the proselyte, and the saving enrolment of the priests are a sacred symbol, registering him amongst those who are being saved, and placing in the sacred memorials, beside himself also his sponsor,—-the one indeed, as a true lover of the life-giving way to truth and a companion of a godly guide, and the other, as an unerring conductor of his follower by the Divinely-taught directions.

This section articulates the final sacrament in the sequence: Confirmation (Chrismation). The proselyte, having been guided by a sponsor and advanced through Baptism and the Eucharist, is now prepared to be fully received into divine communion. The “Hierarch’s seal” symbolizes the sacrament of Confirmation, where the individual is indelibly marked and fortified by the Holy Spirit, thereby completing their initiation and fully integrating them into the sacred order of the Church.

Chiastic Structure

There is a chiastic structure that is inherently embedded with understanding the sacraments this way. To demonstrate the chiastic structure, we can map out the progression as follows:

A. Baptism

– Purification and Enlightenment

– Bringing the individual into the light

B. Eucharist

– Ongoing Nourishment and Enlightenment

– Supporting spiritual progression and union with God

A’. Confirmation (Chrismation)

– Final Sealing and Empowerment

– Fully integrating the individual into the sacred order

In this structure, the Eucharist (B) stands at the center, serving as the pivotal point around which the other sacraments (A and A’) revolve. This chiastic arrangement emphasizes the Eucharist’s crucial role in the spiritual journey, acting as the core sustenance that supports the transition from initial purification (Baptism) to final empowerment (Confirmation).

The progression in scripture

In the divine narrative of salvation, the sequence from Passover to Pentecost encapsulates a profound theological journey, symbolizing the transition from redemption through sacrifice to the empowerment for mission. The crucifixion of Christ, commemorated during Passover, marks the pivotal moment of atonement and liberation from sin, akin to the deliverance of Israel from Egypt. This event, where the Lamb of God offers Himself, sets the stage for a new covenant, inaugurated by His blood. Fifty days later, the feast of Pentecost heralds the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles, marking the birth of the Church and the fulfillment of Christ’s promise. This transformative outpouring empowers believers to proclaim the Gospel and carry forth the mission of the Church.

Within this liturgical and scriptural framework, the sacraments of Baptism, Eucharist, and Confirmation find their rightful place and sequence. Baptism mirrors the purification and initiation experienced during Passover, while the Eucharist provides the spiritual sustenance necessary for the journey. Finally, Confirmation embodies the empowerment and completion symbolized by Pentecost. Together, these sacraments delineate the Christian spiritual path, from the initial call to conversion and purification, through ongoing nourishment, to the fullness of life in the Spirit. Through this lens, we delve into the intricate connections and significance of these sacraments, tracing their divine order and purpose within the life of a Christian.

Baptism: The Foundation

The ministry of John the Baptist, who baptized in the Jordan River, heralded a call to repentance and purification in preparation for the Messiah (Matthew 3:1‒6, Mark 1:4‒5). This sets the stage for the Christian understanding of Baptism as a sacrament of initiation and purification. Jesus’ own baptism by John (Matthew 3:13‒17, Mark 1:9‒11, Luke 3:21‒22) sanctifies the waters of Baptism, establishing a divine precedent. As the heavens open and the Holy Spirit descends like a dove, we witness the transformative power of Baptism. Baptism gives a spiritual rebirth, cleansing individuals from original sin and incorporating them into the Body of Christ. It marks the commencement of the Christian life and entry into the covenant community. Through Baptism, the Holy Spirit begins to dwell within the baptized, initiating a life of grace and sanctification.

The Eucharist: Spiritual Nourishment

The institution of the Eucharist by Jesus during the Last Supper (Matthew 26:26‒29, Mark 14:22‒25, Luke 22:19‒20, 1 Corinthians 11:23‒26) transforms the Passover meal into the sacrament of His body and blood, serving as a perpetual memorial of His sacrifice. In John 6:53-58, Jesus emphasizes the necessity of partaking in His flesh and blood to attain eternal life, underscoring the Eucharist’s role in spiritual sustenance. The Eucharist transcends mere symbolism, offering a real participation in the body and blood of Christ. It is a means by which Christ’s sacrifice is made present and effective in the lives of believers. Analogous to physical sustenance, the Eucharist nourishes the soul, providing the grace necessary for spiritual growth and perseverance in the Christian life.

Confirmation (Pentecost): Empowerment and Completion

Fifty days after Passover, during Pentecost, the Holy Spirit descends upon the apostles (Acts 2:1‒4), empowering them to preach the Gospel and perform miracles. This event marks the birth of the Church and the apostles’ full initiation into their mission. Jesus promises the coming of the Holy Spirit (John 14:16‒17, 26; Acts 1:8), fulfilled at Pentecost, enabling the apostles to fulfill the Great Commission (Matthew 28:19‒20). Confirmation completes the grace of Baptism by imparting the fullness of the Holy Spirit. It seals the baptized, strengthening them to live out their faith boldly.

Just as the apostles were empowered at Pentecost to spread the Gospel, those confirmed are equipped to witness to their faith and actively participate in the Church’s mission.

The sequence of Baptism, Eucharist, and Confirmation mirrors the journey from purification and initiation, through ongoing nourishment, to the fullness of spiritual empowerment. Each sacrament builds upon the previous, creating a coherent and divinely ordered path for the Christian life. The transition from Baptism to Eucharist to Confirmation encapsulates the entirety of the believer’s spiritual maturation, guided by scriptural precedents and enriched by theological depth. This sacred sequence not only reflects individual growth but also the unfolding of God’s salvific plan, resonating through the history of salvation from the Old Covenant to the New.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I must clarify a few points. Firstly, it is not my assertion that the esteemed treatise “Ecclesiastical Hierarchies” advocates for the practice of administering Confirmation years subsequent to the reception of the Eucharist. Rather, it elucidates a certain ontological order of the sacraments. In the nascent Church, the sacraments of initiation were typically conferred concurrently; holy baptism and chrismation were bestowed together, and the deferment of Confirmation was hardly customary. Secondly, I do not endeavor to advance the cause of paedo-communion, although I hold it in favor. Thus, I do not seek to enlist St. Thomas Aquinas as a proponent of administering the Eucharist to infants, given his evident stance against the practice.

The principle aim of this discourse is to demonstrate that, in specific instances, it is both permissible and coherent to administer the Eucharist prior to confirmation. An example to illustrate this will follow from this 8th century text:

As the infants come up from the font the presbyter (priest) makes the sign of the cross out of chrism with his thumb on the crown of their head…. But if a bishop is present, they must be confirmed at once, and afterwards receive Communion. And if the bishop is not there, let them be given Communion by the presbyter, saying thus, “The body of our Lord Jesus Christ protect you for eternal life. Amen” (Supplement created by Benedict of Aniane for the Gregorian Hadrianum, Gregorian Sacramentary “Aniane” 1086‒9)

From the above, it is clear that the administration of the Eucharist prior to Confirmation was never forbidden but deemed acceptable, provided that Confirmation itself would duly follow. Moreover, let no one diminish the profound significance of the sacrament of Confirmation. It is a vital means of grace for the Christian, essential in the sacred endeavor to work out one’s salvation with fear and trembling, enabling the Holy Spirit to dwell within their hearts, crying, “Abba, Father.”

The aim herein is not to undermine the sacrament of Confirmation, but rather to cultivate a more nuanced understanding of the sacraments. It is to deepen our reverence and adoration for the body and blood of our Savior, acknowledging the sacred mysteries with ever-increasing devotion and clarity.

'On the Ordering of the Sacraments of Initiation' have 2 comments

October 1, 2024 @ 8:43 am August Napotnik

This document reads like lofty catholicism until you get to this line: “there are compelling theological arguments that support the reception of the Eucharist prior to Confirmation”.

And of course sources outside of Scripture are leaned on.

It really is a drag debating with Christians who don’t believe in Sola Scriptura whether it’s on Creation, the Sacraments of baptism communion and sabbath, Christian Nationalism…

Scripture isn’t intellectual enough. Is that it??

October 1, 2024 @ 1:32 pm Columba Silouan

That’s the entire point. Man’s Intellect, itself can become a trap and prison. Scripture can reign supreme in our lives without being “Sola” or alone.

The Letter Kills, But The Spirit Gives Life.

Says that right in the Holy Scriptures.

The Word Made Flesh and Dwelt Among Us.

The Word is both The Scriptures and Jesus Christ Himself.

So the Scriptures are NEVER alone by themselves, in spite of having supreme authority.

It’s a paradox. Get used to it. Our Faith is full of them, and full of Mysteries, which keep us Intellectually Humble and Dependent on God and not just our own puny brains.

Hold fast to the Tradition we passed along to you, whether by word of mouth, or by letter.

Again, right there in the Holy Scriptures.

If you fight and quarrel with The Tradition, you fight and quarrel with The Scriptures.

Be Blessed.