the significance of the use of the Apocrypha in Tillotson’s preaching

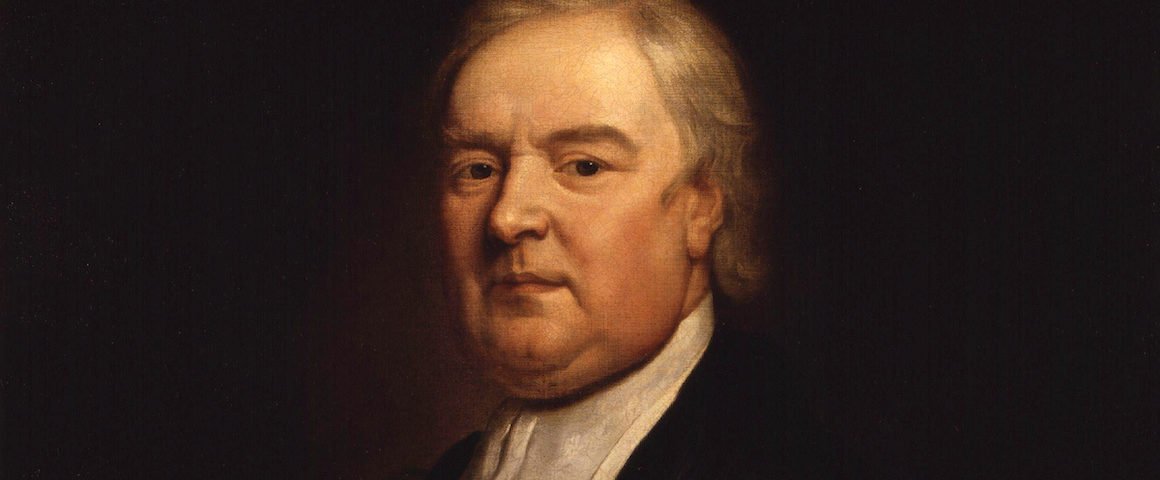

On September 13th, 1689, King William III appointed a commission of bishops and theologians “to prepare such alterations of the liturgy” as would enable “the reconciling, as much as is possible, of all differences among our good [Protestant] subjects.” On the same day, one of those appointed to the commission, John Tillotson, then Dean of Canterbury (1672-1691) and soon to be Archbishop of Canterbury (1691-1694), wrote to William’s advisor, the Earl of Portland, outlining the “concessions, which will probably be made by the church of England for the union of protestants.”[1]

Amongst the concessions Tillotson suggested, to “remove, as much as is possible, all ground of exception to any part of” the Book of Common Prayer, was “leaving out the apocryphal lessons.” The inclusion of the Apocrypha in the lectionary of the Book of Common Prayer had long provoked criticism[2] and had become one of the reasons offered by Non-Conformists for a refusal to accept the Prayer Book.

To achieve the comprehension desired by William, an aim shared by a significant part of the political and ecclesiastical elite, removing the lessons from the Apocrypha was an obvious proposal. It did indeed form part of the ‘Liturgy of Comprehension,’ the revision of the Prayer Book proposed by the commission of which Tillotson was a leading member. The ‘Liturgy of Comprehension,’ however, was reluctantly abandoned in the face of rebellious High Church clergy in the Lower House of Convocation and Tories prepared to politically exploit the issue in Parliament.[3]

As a vocal supporter of comprehension, a contributor to the proposed 1689 revision of the Prayer Book,’ and one of those divines termed by opponents ‘Latitudinarians,’ we might understandably speculate that Tillotson’s preaching – and his sermons were widely admired at the time, continuing to exercise influence throughout the 18th century – would have avoided the Apocrypha. This, however, is not the case.

The Church doth read

In the ten volumes of the 1820 edition of the Works of Tillotson, there are 255 sermons. Despite the Scripture index for these volumes not including the Apocrypha, amongst the sermons there are 46 explicit references to the Apocrypha. There is only one volume (Volume Ten) without any such reference. Of the 255 sermons, 32 – more than 1-in-10 – have references to the Apocrypha. Of the 23 sermons in Volume Two, 5 refer to the Apocrypha. In Volume Three’s 23 sermons, 9 sermons have such references, with Sermon XLII quoting from the Apocrypha on 6 occasions.

These figures alone are suggestive of the Apocrypha significantly present in Tillotson’s preaching. What, however, can we say of how the Apocrypha was used in the sermons? Of the 46 explicit references, the vast majority – 38 – are from two of the ‘wisdom’ books, Ecclesiasticus and the Wisdom of Solomon. Alongside these are a much smaller number from the Books of Maccabees (5) and Tobit (2).

It is immediately obvious that the wisdom literature in the Apocrypha has a particular relevance for Tillotson. The possible theological meaning of this will be addressed below, but at this stage we might note that the emphasis on the Apocrypha’s wisdom books reflects how the 1662 daily lectionary approaches the Apocrypha. 1662 provided for books from the Apocrypha to be read as the first lesson from Evensong on September 27th until Mattins on November 23rd. While these readings included Tobit, Baruch, and the additional material associated with the Book of Daniel, the focus was firmly on Ecclesiasticus and the Wisdom of Solomon, read continuously from October 13th until November 19th.[4]

A similar focus was also to be found in the Book of Homilies. While 30 references to 9 other books of the Apocrypha are scattered throughout the Homilies, there are 68 references to Ecclesiasticus and the Wisdom of Solomon. The 1662 lectionary and the Book of Homilies, then, suggest that an emphasis on the two wisdom books of the Apocrypha was embedded in the formularies of the Church of England.[5]

We also see this pattern reflected in other Church of England divines of the era. The ‘Index of Passages of Scripture’ in Heber’s 15 volumes of The Whole Works of Taylor lists 63 references to 6 books of the Apocrypha, of which 53 are to Ecclesiasticus and the Wisdom of Solomon.[6] The ‘Scriptural Index’ provided for the nine volumes of the 1858 Works of Symon Patrick (Bishop of Chichester then of Ely, 1689-1707) indicates the same emphasis.[7] Of the 103 references to 10 books of the Apocrypha in Patrick’s Works, 66 are to Ecclesiasticus and the Wisdom of Solomon. This points to the pattern in Tillotson’s sermons, a heavy emphasis on the wisdom books of the Apocrypha, reflecting a wider understanding of the Church of England’s use of the Apocrypha.

For example of life and instruction of manners

Tilltson’s references to the Apocrypha in his sermons are explicit: he consistently referred to the books by name. For example, quotations from Ecclesiasticus are invariably prefaced by comments such as “excellent counsel of the son of Sirach,”[8] “the wise son of Sirach,”[9] “that excellent counsel of the son of Sirach.”[10] Likewise, passages from the Wisdom of Solomon a re introduced by phrases emphasising the value of the work: “it is very well expressed in the Wisdom of Solomon,”[11] “excellently said in the Wisdom of Solomon,”[12] and “the wiseman of the Wisdom of Solomon.”[13] Such language quite clearly commended these books of the Apocrypha to hearers and readers of the sermons as cohereing with Scripture.

Only on a single occasion does Tillotson alert his hearers to an Apocryphal book not having the same status as the Canonical books. Referring to the martyrdom of the seven brothers in II Maccabees, he notes “though this history of Maccabees be not canonical.”[14] Despite this, however, Tillotson describes the passage as referring to the hope of the resurrection in Daniel 12:2 and also being referenced in Hebrews 11:35: “the apostle hath warranted the truth of it to us, at least in this particular.” In an earlier sermon Tillotson also referred to the martyrdom of the seven brothers “in the history of the Maccabees,” placing it directly alongside the account of the martyrdom of Saint Stephen in the Acts of the Apostles. A later sermon again refers to the II Maccabees account and reiterates that this is what is being described in Hebrews 11:35: “of these it is the apostle certainly speaks.”[15] In other words, even on the one occasion when Tillotson mentions to his hearers that the book of the Apocrypha he is quoting is not canonical, he emphasizes both then and in his other usages of the passage that it coheres with canonical Scripture.

Nor is this a solitary case of Tillotson illustrating New Testament use of the Apocrypha. He also says of the teaching of Tobit 4:8 on almsgiving “the apostle seems plainly to allude to that passage,” in 1 Timothy 6:17-19.[16] This, of course, provides apostolic precedent for use of the Apocrypha in the Church’s preaching.[17]

The understanding that references from books of the Apocrypha cohere with canonical Scripture is particularly evident when Tillotson uses the Apocrypha to amplify or expound Scripture. He invokes Wisdom 1:11 to illustrate the meaning of James 1:26 and 1 Corinthians 6:10 on the sin of speaking evil of others: “To which I will add the counsel given us by the wise man.”[18] Ecclesiasticus 28:7 is used to expound Romans 2:4 on the patience of God:

[S]ays the son of Sirach. The patience of God aims at the cure and recovery of those who are not desperately and resolutely wicked.[19]

After quoting Lamentations 3:33 – “as the prophet tells us” – he immediately points to “as it is in the Wisdom of Solomon, (chap. i.12, 13.),” explaining affliction and suffering as the “ill use of our own liberty, and free choice.”[20] Similarly, Tillotson follows references to 2 Peter 3:9 and Psalm 90:4, on God’s patience before the last judgement, with “And the son of Sirach likewise,” referring to Ecclesiasticus 18:10.[21] Examples in Scripture of fathers not chastising wayward sons, as was the case with Samuel with his two priestly sons and David with Adonijah, are contrasted with Ecclesiasticus 30:2: “on the contrary, the wise son of Sirach tells us, that ‘he that chastiseth his son shall have joy of him.’”[22] Saint Paul’s declaration in Romans 6:22 that the baptized are called to “have your fruit unto holiness” is amplified by Tillotson quoting Wisdom 6:18-19:

[T]he keeping of God’s commandments is the assurance of immortality, and immortality makes us like to God.[23]

Another way in which the books of the Apocrypha are presented as cohering with Scripture is through Tillotson concluding sermons with such references. There are at least 5 such examples, all referring to either Ecclesiasticus or the Wisdom of Solomon:

I will conclude all with these excellent sayings of the son of Sirach (followed by an extensive quotation of verses from Ecclesiasticus 5, 16 and 18);[24]

I would conclude all with those excellent sayings of the Son of Sirach (Ecclesiasticus 23:9-10);[25]

I will conclude this whole discourse with those weighty and pungent sayings of the wise son of Sirach (Ecclesiasticus 28:1-4);[26]

I will conclude all with the counsel of the wise man (Wisdom 1:12, 13, 16);[27]

I will conclude all with that excellent passage in the Wisdom of Solomon (Wisdom 6:17-18).[28]

Concluding sermons in such a manner certainly emphasized Tillotson’s use of the Apocrypha, with references from the books of Apocrypha used to summarise the teaching of Scripture on the matters addressed by the sermons.

The purpose of Tillotson’s use of the Apocrypha is chiefly, as has been seen, to expound the moral structure of the Christian life. The wisdom of individual charity and almsgiving is illustrated by Ecclesiasticus 29:11-12,[29] while Ecclesiasticus 29:13 is used to demonstrate the importance of charity to national flourishing:

[T]he public charity of a nation hath many times proved its best safeguard and shield.[30]

The importance of the religious and moral formation of children is listed first by “the son of Sirach, among several things for which he reckons a man happy,” Ecclesiasticus 25:7.[31] The need for gratitude towards the Creator “is excellently said in the Wisdom of Solomon: (chap. xi. 23, 24).”[32] A fundamental equality before God, rather than “all those differences and distinctions of men, which make such a noise in this world,” undermines the false claims of wealth:

[A]nd those who were wont to look down with so much scorn upon others, as so infinitely below them, shall find themselves upon an equal level with the poorest and most abject part of mankind, and shall be ready to say, with the wise man in the Wisdom of Solomon, (chap. v.8.) ‘What hath pride profited us, or what hath riches with our vaunting brought us? All these things are passed away as a shadow, and as a post that hasteth by.’[33]

So strict a connexion commonly is there between a man’s thoughts and words, and between his words and actions, that they are generally presumed to be all of a piece, and agreeable to one another”. There is, therefore, a need for wisdom in our speech, avoiding foolish and immodest talk, as seen in the teaching of “the wise son of Sirach: (Ecclus. xxvii. 6, 7).”[34]

For Tillotson, the Apocrypha – as Article VI indicated – was a rich source for illustrating the moral architecture of the life of faith.

Yet doth it not apply them to establish any doctrine

There are other uses of the Apocrypha in the sermons which might at first sight be regarded as sitting uneasily with the constraints of Article VI, addressing doctrinal rather than moral concerns. In a sermon addressing God’s nature and sovereignty, affirming that God is “good and righteous, not only from choice, but from a necessity of nature,” Tillotson says that this is so “according to the reasoning of the author of the book of Wisdom,” quoting Wisdom 12:15-16 before turning to James 1:13.[35]

The above-noted conclusion to a sermon quoting Wisdom 6:17-18 is also significant in this context as the sermon addressed the doctrine of sanctification: “the real renovation of our hearts and lives.” This, Tillotson emphasizes, is a salvific matter:

Faith, considered abstractedly from the fruits of holiness and obedience, of goodness and charity, will bring no man into the favour of God … This must be repaired in us, before ever we can hope to be restored to the grace and favour of God, or to be capable of the reward of eternal life.[36]

A passage from Ecclesiasticus (34:25-26) is also used to illustrate the nature of authentic repentance:

Let us not deceive ourselves; there is one plain way to heaven, by sincere repentance and a holy life, and there is no getting thither by tricks. And without this change of our lives, all our sorrow, and fasting, and humiliation for sin, which at this season we make profession of, will signify nothing.[37]

A sermon celebrating the example of the humility of the Incarnate Lord – “Here is a pattern for us” – points to Ecclesiasticus 10:18 to unfold the significance of such humility:

[I]t does not become us, and yet it is the fashion; we know that we have no cause to be proud, and yet we know not how to be humble. Let the example of our Lord’s humility bring down the haughtiness of men.[38]

In a sermon on the Lord’s Passion, Tillotson provided an extensive quotation from Wisdom 2: 12-20, suggesting that it could be interpreted as prophecy:

This is so exact a character of our blessed Saviour, both in respect of the holiness and innocency of his life, and of the reproaches and sufferings which be met with … that whoever reads this passage can hardly forbear to think it a prophetical description of the innocency and sufferings of the blessed Jesus.

Even if not prophecy, he continues, it was an expression of Jewish theological wisdom:

Or if this was not a prediction concerning our blessed Saviour, yet thus much at least may be concluded from it, that in the judgment of the wisest among the Jews, it was not unworthy of the goodness and wisdom of the Divine Providence to permit the best man to be so ill treated by wicked men.

In each of these examples, Tillotson uses the Apocrypha not to establish doctrine but to reinforce what had become well-established doctrinal positions in the post-1662 Church of England.[39] Each of the sermons has a text from the canonical Scriptures, and makes extensive use of Scriptural quotations throughout. The Apocrypha, then, is not establishing any of the doctrinal issues under consideration. While such usage was illustrative, it nevertheless indicates how – within the boundaries established by Article 6 – the Apocrypha could be used to expound doctrine, drawing out meaning and implications.

Tillotson’s use of the Apocrypha also adhered to Hooker’s defense of its public reading as “profitable instruction … for the better understanding of scripture”:

For the people’s more plain instruction (as the ancient use hath been) we read in our Churches certain books besides the scripture, yet as the scripture we read them not.[40]

Hooker quotes from the Prologue to Ecclesiasticus – in which the author presents the work as an exposition of “the law, and the prophets, and other books of our fathers” – to illustrate how the reading of the Apocrypha is a form of “public instruction” in the Scriptures: “Their end in writing and ours in reading them is the same.”[41]

The Apocrypha and renewing sapiential preaching

Rather than explicitly locating Tillotson within a ‘Latitudinarian’ tradition – mindful that the meaningfulness of the category ‘Latitudinarian’ has increasingly been convincingly challenged[42] – we might suggest that Tillotson’s use of the Apocrypha, with its emphasis on the Wisdom books, stands within a tradition of sapiential theology in the post-Reformation Church of England, derived from Hooker, sustained by the Cambridge Platonists, and then becoming a defining feature of Anglican life from 1660 to 1832, promoted by ‘Latitudinarian’ and High Church alike. Torrance Kirby has said of Hooker, noting the influence of the Book of Wisdom:

Hooker’s appeal to the principles of sapiential theology with their defining emphasis on the yoking together of wisdom, both natural and revealed, constitutes the mainstay of his apologetic throughout his great treatise … the grand cosmic scheme of laws set out in Book I is intended to place the particulars of the controversy within the foundational context of a sapiential theology.[43]

Williams likewise describes Hooker as “manifestly a sapiential’ theologian.”[44] He states of Hooker’s words at the close of Books I of the Laws – “her seat is the bosom of God, her voice the harmony of the world” – they are “very close to those of the great hymns to Wisdom in the sapiential books.” Williams continues:

The sudden transition here to the feminine pronoun would alert any scripturally literate reader to the parallel with the divine Sophia of Proverbs, Job and (most particularly) the Wisdom of Solomon.

Tillotson, inheriting this tradition from the Cambridge Platonists,[45] embodied it to the extent that, as Nockles notes, the “ethical and prudential tone” of both (to use rather imprecise terms) High and Broad Church in the late 18th and early 19th centuries “has been called ‘Tillotsonian.’”[46] Such sapiential theology was not a proto-liberalism,[47] and “much less” the precursor of “the Age of Reason than traditionally has been supposed.”[48] As W.M. Spellman has said of the role of those, like Tillotson, whom he terms “the moderate churchmen”:

If the appeal to reason be a measure of an affinity with Deism, then the moderate churchmen can no more be identified as the sole progenitors of that hostile force than the medieval successors to Aquinas.[49]

This is suggestive of how Tillotson’s use of the Apocrypha, with its pronounced emphasis on the Wisdom of Solomon and Ecclesiasticus, points to a Hookerian Thomism,[50] in which reason and wisdom, rather than being anticipations of Enlightenment accounts, flow from and give expression to a natural order “drenched-with Deity.”[51] For Tillotson’s preaching, this took particular expression in how reason and wisdom should shape the Christian moral life, providing the practical exposition of one of his most often quoted verses of Scripture (appearing 43 times in the sermons), Titus 2:12: “Teaching us that, denying ungodliness and worldly lusts, we should live soberly, righteously, and godly, in this present world.”

Tillotson’s use of the Apocrypha, and the theological context from which it arose, is suggestive of the need for contemporary sapiential theology and preaching to attend to the Apocrypha, particularly to its Wisdom books. Ecclesiasticus and the Wisdom of Solomon act as a commentary on the Canon’s wisdom teaching, bringing us to discern its extent and implications. Both books are rooted – albeit in different ways – in the teaching of Israel, again reminding the Church of its fundamental dependence upon “the good olive tree” unto which we have been grafted.[52] As David A. deSilva notes, Ecclesiasticus emerged from the scribal traditions in Jerusalem “at a time when tensions concerning assimilation to the dominant culture of Hellenism were mounting,” while the Wisdom of Solomon was “a product of Alexandrian Judaism.”[53] They therefore offer different (but not incompatible), enriching readings of Israel’s wisdom tradition.

Christian attentiveness to Ecclesiasticus and the Wisdom of Solomon was a practice of the early Church. Wisdom had a “most pervasive influence” on Saint Paul, says de Silva, and a similarly “pervasive influence” on patristic theologies, particularly Augustine.[54] Ecclesiasticus “had a thorough and profound impact on the authors of the New Testament,” while its “formative influence … on Christian ethics” was “very strong from the beginning.”[55] We should, therefore, heed Article VI: “the Church doth read” these books for good reason, after the example of Israel, in communion with the writers of the New Testament, and following the pattern of the primitive Church. In doing so, we are drawn to discern the reason, truth, and light of the Canon’s wisdom teaching, allowing it to more fully shape the Church’s proclamation and the Christian life.

In a recent article addressing the challenges of life during the Covid-19 pandemic, a secular commentator in the United Kingdom stated:

Like millions of other faithless people, I have not even the flimsiest of narratives to project on to what has happened, nor any real vocabulary with which to talk about the profundities of life and death … For many of us, life without God has turned out to be life without fellowship and shared meaning – and in the midst of the most disorientating, debilitating crisis most of us have ever known.[56]

Tillotson, I accept, may be an unlikely figure for contemporary Anglicans to consider: his humane, urbane Protestantism would be rather quickly dismissed by devotees of both Alpha and Radical Orthodoxy. The use of the Apocrypha in his preaching, however, does offer us an example of why “the Church doth read” those wisdom books. It shows how this can contribute to the Church offering a moral vision capable of addressing “the profundities of life and death” in light of the wisdom of the Scriptures, setting forth a “shared meaning” rooted in the One in whom we live, and move, and have our being.

- See the 1754 ‘Life of Tillotson’ by Thomas Birch in The Works of Dr. John Tillotson (1820), Volume I, p.cxviii-cxxi. All references to Tillotson’s works in this essay are to the 1820 edition. ↑

- The 1571 ‘Admonition to Parliament’ rejected the provision for lessons from the Apocrypha on the grounds that “nothing else but the voice of God and holy Scriptures, in which only are contained all fullness and sufficiency to decide controversies, must sound in his church”. In 1641 a group of anti-Laudian divines appointed by Parliament urged consideration to be given to “Whether Lessons of Canonical Scripture should be put into the Kalendar instead of Apocrypha”: see A copie of the proceedings of some worthy and learned divines, appointed by the Lords to meet at the Bishop of Lincolnes in Westminster touching innovations in the doctrine and discipline of the Church of England. Together with considerations upon the Common prayer book (1641). ↑

- Details of the proposed revision and a short account of the opposition of the Lower House of Convocation can be found in Procter and Frere A New History of the Book of Common Prayer, Chapter VIII. ↑

- See the discussion of the 1662 lectionary in Drew Keane ‘The Annual Cycles of Bible Reading in the Prayer Book, Pt.1’, North American Anglican, 9th March 2020. ↑

- As noted in the ‘Index of Texts of Scripture’, Book of Homilies (1859/2008), John Griffith ed., p.604-605. ↑

- Reginald Heber, The Whole Works of the Right Rev. Jeremy Taylor (1829), Volume I, p.203-4. ↑

- Alexander Taylor, The Works of Symon Patrick (1858), Volume IX, p.689. ↑

- Volume II, Sermon XVIII ↑

- Volume III, Sermon XLII, p.262. ↑

- Volume VI, Sermon CCXVI, p.212. ↑

- Volume IV, Sermon LXXV, p.408. ↑

- Volume V, Sermon XCIX, p.251. ↑

- Volume VIII, Sermon CLXXIX, p64. ↑

- Volume VIII, Sermon CLXXVI, p.11. ↑

- Volume IX, Sermon CCXIV, p.104. ↑

- Volume II, Sermon XXIII, p.334. ↑

- We might note that Tillotson here contradicts Burnet on Article VI. In An Exposition of the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (1699), Burnet declares of the books of the Apocrypha: “None of the Writers of the New Testament cite or mention them”. ↑

- Volume III, Sermon XLII, p.264. ↑

- Volume VII, Sermon CXLIX, p.96. ↑

- Volume VII, Sermon CXLV, p.24. ↑

- Volume VII, Sermon CXLVIII, p.77. ↑

- Volume III, Sermon LII, p.513. ↑

- Volume VIII, Sermon CLXXXV, p.172. ↑

- Volume II, Sermon X, p.35. ↑

- Volume II, Sermon XXII, p.308. ↑

- Volume III, Sermon XXXIII, p.54. ↑

- Volume III, Sermon XXXV, p97. ↑

- Volume IV, Sermon CIX, p.425. ↑

- Volume II, Sermon XVIII, p.210. ↑

- Volume III, Sermon XXXIX, p.193. ↑

- Volume III, Sermon LIII, p.543. ↑

- Volume V, Sermon XIC, p.251. ↑

- Volume VIII, Sermon CLXXIX, p.64. ↑

- Volume IX, Sermon CCXIV, p.104. ↑

- Volume IV, Sermon LXXXIII, p.545. This issue had particular relevance to debates over predestination. Tillotson was here echoing Cambridge Platonist Ralph Cudworth’s 1647 Sermon before the House of Commons: “I may be bold to add that God is therefore God, because he is the highest and most perfect good, and good is not therefore good because God out of an arbitrary will of his would have it so”. See Charles Taliaferro and Alison J. Teply, Cambridge Platonist Spirituality (2004). p.69. ↑

- Volume IV, Sermon CIX, p.425. ↑

- Volume II, Sermon X, p.31. ↑

- Volume VIII, Sermon CLXXXVIII, p.242. ↑

- As Stephen Hampton has shown in Anti-Arminians: The Anglican Reformed Tradition from Charles II to George I (2008), while a vibrant Reformed tendency continued to exist in the post-1662 Church of England, it was a minority in a mostly anti-Calvinist, ‘Arminian’ Church. Thus Tillotson’s teachings on the sovereignty of God and the relationship between faith and works, while they would have been questioned by the Reformed minority, would have been uncontroversial to the majority. Hampton notes, for example, that “the extent of the overlap” between the increasingly dominant teaching of George Bull of faith and works and that of Tillotson was “truly remarkable” (p.63). ↑

- Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity V.20.1 & 8. ↑

- V.20.11. ↑

- See, for example, John Marshall ‘The Ecclesiology of the Latitude-men 1660–1689: Stillingfleet, Tillotson and Hobbism’ in The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Volume 36, Issue 3, July 1985, pp.407-427 and John Spurr ‘Latitudinarianism’ and the Restoration Church’ in The Historical Journal, Volume 31, Issue 1, March 1988, pp.61-82. ↑

- Torrance Kirby, ‘The ‘sundrie waies of Wisdom: Richard Hooker on the Authority of Scripture and Reason’ in The Oxford Handbook of the Bible in Early Modern England, c.1530-1700, pp.165 & 166. Kirby points to Hooker’s famous declaration that “The bounds of wisdom are large, and within them much is contained” (II.1.4) as relying on Wisdom 11:20: “thou hast ordered all things in measure and number and weight”. ↑

- Rowan Williams ‘Richard Hooker: Philosopher, Anglican, Contemporary’ in Anglican Identities (2004), p.40ff. ↑

- The 1753 ‘Life of Tillotson’ by Thomas Birch provides a roll-call of the Cambridge Platonists in describing their influence on Tillotson: “As he got into a new method of study, so he entered into friendships with some great men, which contributed not a little to the perfecting his own mind. There was then a set of as extraordinary persons in the university, where he was formed, as perhaps any age has produced ; Dr. Ralph Cudworth, master of Christ’s College; Dr. Benjamin Whichcot, provost of King’s; Dr. Henry More, and Dr. George Rust, fellows of Christ’s, and the latter afterwards Bishop of Dromore, in Ireland; Dr. John Worthington master of Jesus; and Mr. John Smith , fellow of Queen’s College”, Volume I,p.iv. Tillotson preached at the funeral of Whichcote, describing him as “a great encourager and kind director of young divines”. The sermon can be found in Volume II, p.351ff. ↑

- Peter B. Nockles, The Oxford Movement in Context: Anglican High Churchmanship 1760-1857 (1994), p.185. ↑

- See, for example, Nathaniel Culverwell: “One light does not oppose another – ‘the lights of faith and reason’ may both shine together, though with far different brightness; ‘the candle of the Lord’ is not impatient of a superior light, it would both ‘bear an equal and a superior’. Taliaferro and Teply, op. cit., p.138. Also W.M. Spellman The Latitudinarians and the Church of England, 1660-1700 (1993), p.10, notes of the ‘Latitudinarians’ that they “had a view of human nature which had very little in common with the more confident assumptions rightly associated with the Age of Reason”. ↑

- Spellman op.cit., p.6. ↑

- Ibid., p.158. ↑

- See Jared Tomlinson, ‘Richard Hooker and Thomas Aquinas’, North American Anglican, April 24 2020, in which Hooker’s relationship with Aquinas is described as one “of critical and creative dependence”. ↑

- The term is taken from C.S. Lewis’ description of Hooker’s vision in English Literature in the Sixteenth-Century (1954). ↑

- Romans 11:24. ↑

- David A. deSilva Introducing the Apocrypha: Message, Context, and Significance (2002), p.127 and p.153. ↑

- Ibid., p.150 and p.152. ↑

- Ibid., p.193 and p.197. ↑

- John Harris ‘How do faithless people like me make sense of this past year of Covid?’, The Observer, 28th March 2021. ↑

'Listening to the wise son of Sirach' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!