Sometime in the early 1980s, just about the time Bob Dylan was recording Infidels, a little girl in Shreveport got a plush toy as a gift from her dad. It was vaguely Easter themed—a plump oval, the bottom half a colorful sateen eggshell, the top half a fat, fuzzy chick. It was adorable, just the thing for a little girl to squeal a thank you over, and the most vivid memory I have of that moment is striving not to crumple into sobs, because I knew that it and all the other little treasures of my six-year-old heart were all going to burn up in a fire with the rest of the earth after we were raptured away.

Most critics saw Infidels as Dylan’s return to more “secular” music after the three albums comprising his born again phase. Among the many outtakes was a song he’d penned called “Death Is Not the End,” which didn’t actually appear until 1988’s Down in the Groove. In 1988 I wasn’t allowed anywhere near devilish rock music; my first exposure to the song was in my early twenties when I discovered Nick Cave and heard the weird, lilting, booze-soaked cover he sang with Kylie Minogue and Shane McGowan for Murder Ballads.

In my twenties I worried less about my stuffies suffering apocalyptic incineration and more about being raptured before I could, ahem, get married. The joys and desires of enfleshed existence seemed so real and pressing compared to that vague future state I couldn’t even really picture. I can remember stretching out my hand in front of me as I drifted off to sleep, thinking, I will miss this—this flesh, this body, this thing which feels so much like me—and tears starting again.

Somehow I had missed that Christians actually believe in and hope for the resurrection of the body. How thrilled I was to discover these words from N. T. Wright’s Surprised By Hope.

You are not oiling the wheels of a machine that’s about to roll over a cliff. You are not restoring a great painting that’s shortly going to be thrown on the fire. You are not planting roses in a garden that’s about to be dug up for a building site. You are—strange though it may seem, almost as hard to believe as the resurrection itself—accomplishing something that will become in due course part of God’s new world.

The promise of the resurrection is part of a larger hope that all things will be made new. Our bodies matter. Material creation matters. This life matters. Working to bless your neighbors and ease suffering and right wrongs and pursue Justice-with-a-capital-J matters. What an exhilarating message for a young person eager to Make a Difference and Do Important Things. In retrospect, the idea of being snatched away and leaving everything to perish now seemed escapist, justification for the abandonment of any attempt to do temporal good. My new perspective failed to account for all the “escapists” who ran crisis pregnancy centers, adopted orphans, and bought Christmas presents for kids they didn’t know, but no matter—I had a new framework for my lifelong preoccupation. It is a running joke in my marriage that my husband never has to ask what I’m thinking about, because the answer is always, “Death.” You can see how “Death Is Not the End” appealed to me.

On first listen, the song seems straightforward enough: when faced with sadness, isolation, disaster, disappointment, hopelessness, and death, we have this to comfort us, that death is not the end. Any Christian can recognize a message of hope. The promise of the resurrection means we can look forward to more, something beyond this sorrowful, broken old world.

When you’re sad and when you’re lonely, and you haven’t got a friend

Just remember that death is not the end

And all that you’ve held sacred falls down and does not mend

Just remember that death is not the end

Not the end, not the end

Just remember that death is not the end

On closer inspection, we begin to grow uncomfortable. The refrain is repeated so much that it begins to sound like either a “Don’t Fear the Reaper”–style invitation to suicide or, perhaps, a notice that remembering death isn’t the end rarely feels sufficient to address the suffering in front of us. Does it really help to tell yourself, when you’re friendless and in mourning, that death isn’t the end? Hope on the other side of it is all well and good, but what about all the years of suffering in between? Can any state of blessedness make up for all this loneliness, disillusionment, confusion, and despair?

“Remember, O Lord, against the Edomites the day of Jerusalem, how they said, ‘Lay it bare, lay it bare, down to its foundations!’” Psalm 137 cries out in lament over Israel’s exile and the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple. The city of David and the temple raised by his son have both been destroyed. The Psalmist wants an end to this suffering— but also articulates a longing for retribution: “O daughter of Babylon, doomed to be destroyed, blessed shall he be who repays you with what you have done to us! Blessed shall he be who takes your little ones and dashes them against the rock!” It seems that when we’ve been ripped from our home and seen our sacred places pulled down, we not only don’t want to hear how death isn’t the end, we want death for the end, the end of those who’ve wronged us.

When you’re standing on the crossroads that you cannot comprehend

Just remember that death is not the end

And all your dreams have vanished and you don’t know what’s up the bend

Just remember that death is not the end

Not the end, not the end

Just remember that death is not the end

When the storm clouds gather ’round you, and heavy rains descend

Just remember that death is not the end

And there’s no one there to comfort you, with a helpin’ hand to lend

Just remember that death is not the end

Not the end, not the end

Just remember that death is not the end

The rains descended on Noah and on all the rest of the earth, and it certainly seemed like death was the end for almost everybody. Job, sitting there covered in sores and ruin, impoverished of wealth and offspring, found another poverty of comfort from his friends. Who hasn’t read Job and thought, well, it’s nice he had some new kids but that doesn’t actually bring the old ones back? Dead’s dead. It seems like the height of callousness to say to someone who’s lost a child, “Chirk up! Death isn’t the end, you know.” Wouldn’t that just head us right back to escapism?

But we’re enlightened now. We are ever so much cleverer and less muddled than the fundamentalist rapture advocates. We’ve moved beyond the knee jerk pie-in-the-sky mentality where, as Wright himself caricatured it, “Any attempt to work for God’s justice on earth as in heaven is condemned as the sort of thing those wicked anti-supernatural liberals try to do.”

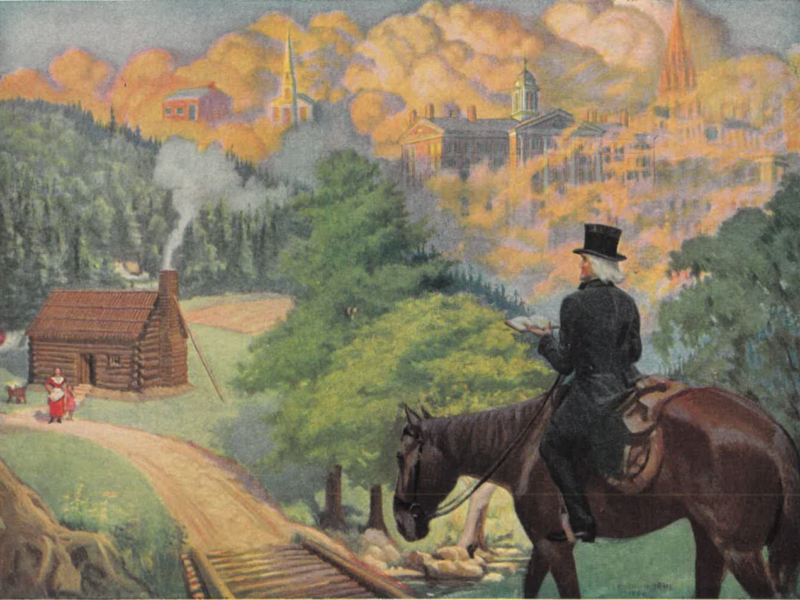

When the cities are on fire

With the burning flesh of men

Just remember that death is not the end

And you search in vain to find

Just one law-abiding citizen

Just remember that death is not the end

Not the end, not the end

Just remember that death is not the end

Blazing cities and burning flesh call up terrible natural disasters and the worst obliterations we’ve so far worked on one another: London, Dresden, Nagasaki. And there’s no reason to believe we won’t do more, and worse. The scale of horror is so huge we cannot comprehend it. It’s so huge that we might fear that nothing we can do will solve the problem. And to this we merely say, “Death is not the end”?

Or, if we’ve fallen into the opposite error, we proclaim that we will work for justice even harder, as if any amount of Doing the Work is going to be an ultimate fix for this mess. Gaze on the litany of horrors long enough, as the song so helpfully invites us to do, and we will come to the end of ourselves, and the good works we treasure look like one more stuffed toy tossed into the conflagration.

Ah, but a vain search for a law-abiding citizen reminds us of another flaming city. For ten righteous men God would have preserved Sodom and Gomorrah, but they weren’t there. They’re not here, either, because who among us can keep the law?

And that’s what we come to—we reel back from injustices seemingly impossible to rectify, but we can’t handle justice either, especially when it comes for us. We yearn for those bad people over there to be subject to judgment, but if we have any self-apprehension at all we fear judgment for ourselves. But regardless of our anticipation and dread, “our whole life is nothing but a race toward death,” as St. Augustine put it, and man “begins to die so soon as he begins to live.” How can we escape?

Oh, the tree of life is growing

Where the spirit never dies

And the bright light of salvation shines

In dark and empty skies

The dark and empty sky of the hopeless human mind is a starless void indeed. But from the garden where the tree of life stood, to the city where it will stand, is a record of faithfulness we can consult to find what it means for us that death is not the end. And in the oldest bit, Job, whose suffering we wanted to take so seriously, took his own suffering so seriously that he said

For I know that my Redeemer lives,

and at the last he will stand upon the earth.

And after my skin has been thus destroyed,

yet in my flesh I shall see God,

whom I shall see for myself,

and my eyes shall behold, and not another.

Oh.

In a 1984 interview in Rolling Stone, Dylan plainly says he does believe in some kind of afterlife. But he was at the time also on a slide out of whatever faith he had, so who knows what he meant. That opacity of meaning is also what gives the song its power—the more we contemplate it, the more we walk around humming the catchy refrain, the more we are pressed to consider its unspoken and unresolved questions. Whether honest statement of hope or searing sarcastic indictment, here we are, just like the song says, hemmed in behind and before by intolerable injustice and intolerable justice, the immutable fact of mortality growing closer with every breath. And who will deliver us from this body of death?

'Death Is Not the End' has 1 comment

April 25, 2022 @ 9:41 am Duncan Cary Palmer

Death?

Scarcely the beginning for Jesus’ many beloved:

https://hive.blog/story/@creatr/whispering-hope-forbidden-tales-from-your-bright-future