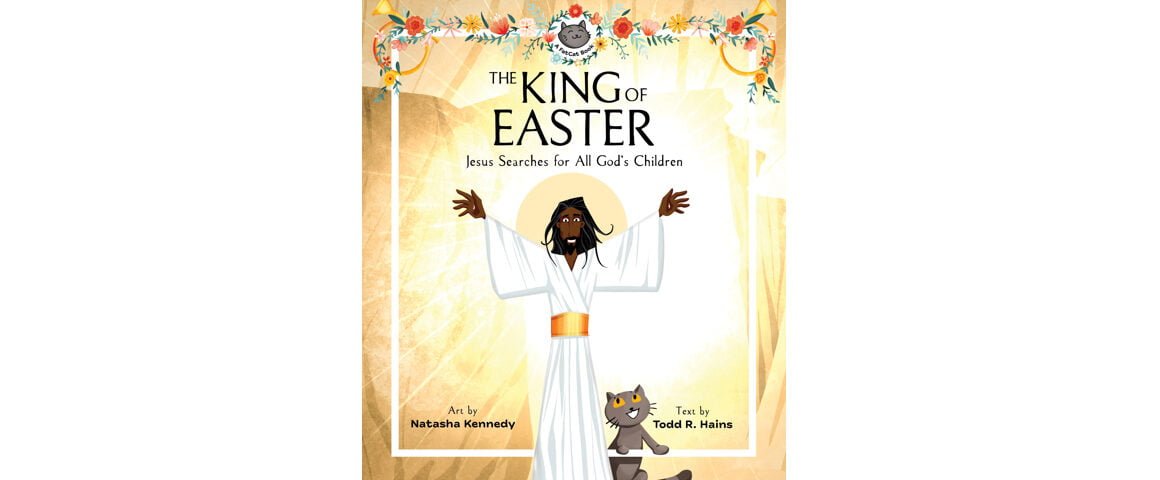

The King of Easter: Jesus Searches for All God’s Children. By Todd R. Hains. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2023. 56 pp. $17.99 (cloth).

My children look forward to different holidays as they approach on the calendar. How long until Christmas? When will it be Halloween again? As we march through the seasons of the Church Year I invite them to recall their significance. What is Advent about? Waiting for Jesus. What is Christmas about? The Son of God became the Son of Man that the sons of men might be sons of God. There are many ways to draw our children in to the faith, to explain it to them, to catechize them in the way that they should go, but what a support it is to have thoughtful, beautiful resources to aid us in this work. It is with great joy, then, that I can celebrate another Lexham Press release from the FatCat team, this time to celebrate the King of Easter, who seeks out the lost that he might save them.

The King of Easter begins with FatCat and Jesus together before an empty table, proclaiming that “Jesus is the King of Easter! He finds who is lost. Who is lost, he saves.” Clearly this table must be filled with guests, and so the book invites us to see just who Jesus seeks and saves.

The book begins with the incarnation and the salvation extended to Mary, who was full of grace and who, when hearing the angel’s word, believed and said, “Let it be unto me according to your word” (Luke 1:26‒38). With a page like this I can imagine parents taking the simple truth of the page, “His mother Mary, who believed the angel’s word – did the King of Easter find and save her? Yes!” (3) and expanding upon it. Mary, of course, serves as a type of the Church, that blessed company of the faithful over whom the Spirit hovers that Christ might dwell in our hearts (Eph 3:14‒19). Why was Mary saved? Why is the Church saved? Because we, like Mary, believe the word of the Lord and receive its consequences in meek obedience.

Following this we meet “Faithful Simeon and Anna, who waited for their Savior” (5). As we recently celebrated at the Presentation of Our Lord Jesus Christ in the Temple, so we see Joseph and Mary with two pigeons for their purification. Anna stands beside them, looking joyfully at Jesus, as Simeon receives and lifts the young Jesus in his arms, praising the Lord that his “eyes have seen your salvation” (Luke 2:30). Here there are calls to give thanks to God for the birth of a child (perhaps a newborn sibling), to discuss the poverty of Mary and Joseph (Lev 12:8), how God works through both men like Simeon and women like Anna, and how those who seek the Lord will find him (Isa 55:6‒7).

A couple pages later we find Jesus seeking out Matthew, who we are told “was hated by his people” (9). And yet, the King of Easter found and saved him. By now we have a small group that has gathered to follow Jesus: Mary, Joseph, John the Baptist, Anna, and Simeon. As Jesus approaches the tax collector we see Mary and Joseph smiling at the Savior’s welcome, but John has folded his arms and looks perturbed while Anna is shocked and Simeon is concerned. How easy it would have been to present the saved to be just as welcoming as Jesus, and yet the reality of our own uncertainties is reflected in the saints. Matthew? The tax collector? Surely Jesus is here to condemn him. No, he came to Matthew to find him and save him. Even if someone is unliked, a classmate, a neighbor, a cousin, or even our child, Jesus came to seek and to save the lost (Luke 19:10).

A bit later we see Jesus, shrouded in darkness and hanging from the cross. Above him we see the reason for his punishment: “Jesus the Nazarene, the King of the Jews” written in Hebrew, Latin, and Greek. His crowd of followers surround him at the foot of the cross, looking on as the one who has drawn all men to him (John 12:32) even now draws another with him into the Kingdom. On his left a thief stares off in anger, receiving the just recompense for his crime, but on Jesus’ right the penitent thief receives salvation. Nothing in his hand he brings, simply to the cross he clings, naked, come to him for dress, helpless looking to him for grace. Once again someone who seems unworthy is made worthy because he believes in the word of the Lord.

A few pages later we find “Our parents Adam and Eve, who disobeyed God’s command” (25). There, in the heart of the earth (Matt 12:40), we see Jesus extend his nail-pierced hands towards Adam and Eve as the ever-growing followers of Jesus rejoice to see the one who is free among the dead (Ps 88:5) set the captives free (Ps 68:18‒20). Above them waves a banner with the opening line of Psalm 118 inscribed in Hebrew, “Oh give thanks to the Lord, for he is good; for his steadfast love endures forever!” That love that even death cannot stop (Rom 8:38‒39) is reaching out for the first sinners. Leading the group we find the penitent thief, no longer naked, but clothed in a white robe (Rev 7:9) who now leads the people of God in joyful procession as the crucifer. Adam rejoices and Eve, with tear-filled eyes, receives the promise given from long ago, that her seed would bruise the head of the serpent (Gen 3:15), binding him (Matt 12:29), and delivering them from the one who has power over death (Heb 2:14‒15).

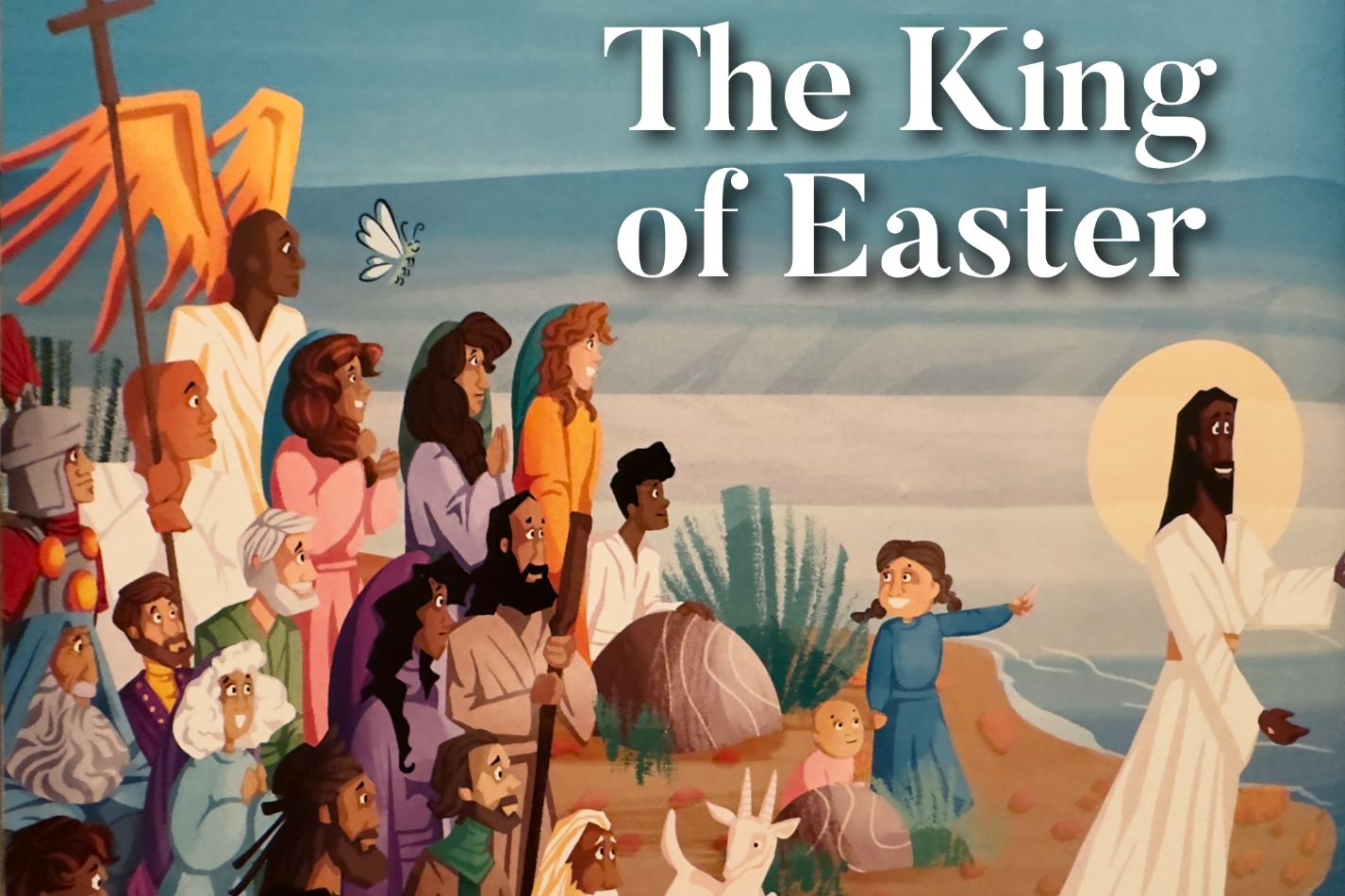

As Jesus exits his tomb, we find him surrounded by those whom he has saved, all shouting in praise with instruments in their hand to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus. A banner billows in the foreground, announcing the words that Zaccheus clung to: Salvation has come to this house (Luke 19:9). This house, this congregation, made up of the living and the dead, sings praise to the one who has conquered death and offers life to all, even to those who went down into the dust (Ps 22:22‒31).

As we continue through the book, we find Jesus still drawing others to himself. Those who were despondent at the death of Jesus he assures with his Word and Sacrament (Luke 24:13‒32). The one who doubted he receives, inviting him to feel the holes in his hands, feet, and side (John 20:24‒29). The one who denied Jesus leaps for joy into the sea in order to greet Jesus while FatCat pats at the fish roasting on the shore (John 21:1‒19), there to learn that Jesus would not only restore him but charge him to tend the lambs and the sheep.

In the end we find ourselves back at the table, no longer empty, but filled with those who waited for Jesus, who sought Jesus, whom Jesus sought, who denied Jesus, who disbelieved Jesus, who fought against Jesus, and who in the end were won over by his mercy and grace towards those who were willing to trust in him. Towards the end of the book a note to parents reminds us:

Some of the lost don’t seem very lost – the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist. Others seem too lost – the thief on the cross and Saul. Some are searching for Jesus – Simeon, Zaccheus, and Mary Magdalene. Others aren’t looking for Jesus at all – Matthew the tax collector, the centurion at the cross, and the travelers on the road to Emmaus. But they all are lost. “All we like sheep have gone astray” (Isaiah 53:6). They all need Jesus. “He is our God, the God from whom salvation comes; God is the LORD, by whom we escape death” (Psalm 68:20 BCP). When Jesus finds the lost, he brings them out of death and into life. He gives himself and all that he has to us. And that’s the story of Easter. On Easter Sunday, King Jesus rose from the grave, defeating sin, death, and the devil and bringing us forgiveness, life, and salvation. (49‒50)

I have only two qualms with this book, and they are minor. First, the teaching that the centurion who said, “Surely this man was the Son of God,” was saved. Perhaps he did come to believe in Jesus (Luke’s mention that he praised God, Luke 23:47, may be a hint in this direction), but it’s conjecture at best. Second, we are told that Saul “found and killed Jesus’ friends.” While Saul did breathe out murderous threats (Acts 9:1) and approved of Stephen’s murder (Acts 8:1), there is no evidence that he actually killed anyone himself. He was, of course, directly involved in the murder of Christians, so using “killed” in a very broad sense may be permissible. Qualms indeed.

What can I say? As parents with a young family (5, 3, and 1), my wife and I need help raising our kids in the faith. We need resources to aid us in the arduous task of taking wild animals and teaching them to be people who by God’s grace can dine at his table (Ps 23). The FatCat series of books continue to be such a treasure in this vocation of parenthood. Todd Hains’ writing is excellent, profound enough for a man to meditate upon and simple enough for a young child to understand and excitedly announce, “Yes!” to Jesus’ extension of mercy.

The art by Natasha Kennedy continues to be nothing short of remarkable. Her images invite deep contemplation of the story of our salvation and the ways in which God’s grace extends even into seemingly impossible circumstances. The invitation at the end of the book to search not only for FatCat but also for Jesus and his friends not only invites repeated readings, but investigation into the Scriptures for the origins of these characters. And Wormy! I’ll leave that as a surprise to discover when you go through the book yourself. I would be remiss not to celebrate Kennedy’s willingness to include original languages in the art. Many might shy away from such things because most children (and adults) cannot read Hebrew, Greek, or Latin, but herein we see the opportunity for devotion. When I was a pre-teen I drew the crucifixion over and over again, and one of the things I wanted to do was include the sign over Jesus’ head as it actually would have appeared in Aramaic, Greek, and Latin. This attention to detail invites children to explore the Biblical and Patristic languages, gives opportunity to talk about translation, and helps children recognize that they are part of something that may seem or feel foreign due to the original language barrier, but that has been brought near to them through the hard work of translation by those who follow Jesus.

Simply put, The King of Easter is a delight that I heartily recommend to families and churches as a resource to help our children celebrate the one who was born, lived, suffered, died, descended, rose again, ascended, and will return to reconcile God’s children to the Father.

'Book Review: “The King of Easter”' has 1 comment

March 19, 2023 @ 3:47 pm Seth

I also have very much enjoyed the FatCat series and look forward to this one. I hope they have a ten commandments book in the works, in keeping with the catechism approach.

I can’t help but find it off putting that the artist depicts Jesus as so dark-skinned. It’s natural for cultures to imagine Jesus through their own cultural lens, so I do not think there is underlying racism in old European depictions of “white Jesus” or any other inculturated depiction. Yet, we do know better today. We generally know what a 1st century Semitic man was most likely to look like. Jesus is not merely a reflection of our cultural and ethnic background. He had a face. He still does. So I find this book’s depiction of very dark skinned Jesus off-putting in the same way I find blonde haired, blue-eyed Jesus off-putting. There’s grace if that’s done from ignorance. But otherwise it seems like an intentional mis-portrayal of what our Lord was most likely to have looked like, which is especially confusing for the blossoming imagination of a young child.