House of 49 Doors: Entries in a Life. By Laurie Klein. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2024. 114 pp. $14.00 (paper).

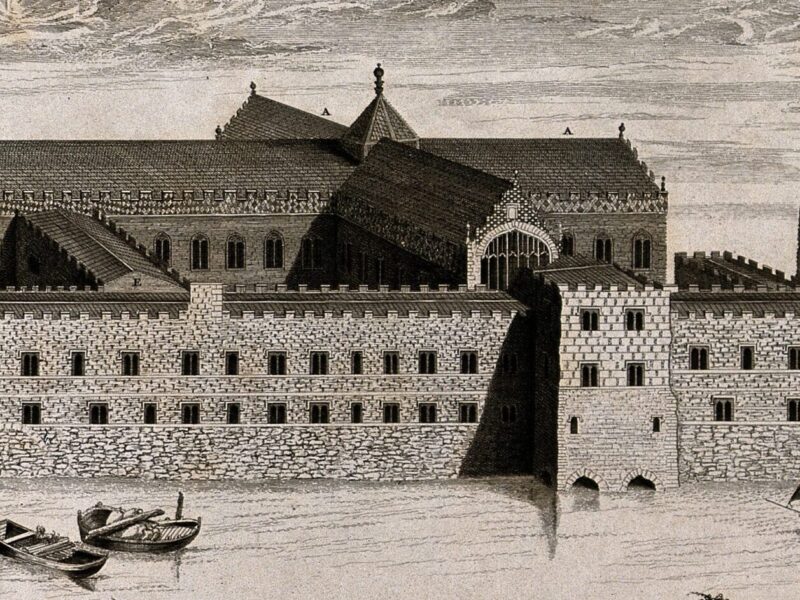

The prospect of entering a house ranged with 49 doors might seem perplexing, if not daunting, to the most intrepid explorer. One may expect that these primary architectural markers imply a grandiose construction that will appear asymmetrical and uneven. Anyone who has visited the Winchester House in San Jose, California or the Wexner Center for the Arts on the campus of Ohio State University knows the otherworldly feeling of surrealistic designs. Such spaces hover in the liminality between form and function: half-necessity, half-impressionistic, half-novelty, half-absurdity. To represent such oblong and labyrinthine spaces in words requires a finesse of grandeur elusive to most poets. Yet this is precisely the aim of Laurie Klein’s House of 49 Doors: Entries in a Life. Klein composes a collection of breadth and durability that recreates in words the meaning of her childhood home, Fowler House, and the personal histories of its inhabitants. The purposes of this book are, no doubt, many, but there are two that I think highlight the strengths of the poet and may humbly serve to recommend her art.

As an impressionistic volume, the poems rely heavily on sound—though the more onomatopoeic than, say the repetitive variety of alliteration. Surely the poet would find the grammar of rhyme and meter out of place in works so immersed in subjectivity. Many pieces are cut through with the sizzling of lightning, of fishlines and radiators, the snap of diving, and many other sounds that make up rural life. In addition to creating heightened sensations, these also serve as a reminder that poetry is first and foremost an aural medium, meant to nurture the ear as well as the eye. For the reader who may sometimes struggle to see the setting and characters as they are stretched out by time and space, these moments of intensification concentrate the experience to sharp points, bringing us continually back into the moment.

As an autobiographical volume, Klein leads her readers through the rooms, hallways, and stairways of the great house. These places become the physical and mental architecture lived in at various times by her two alter egos: the young child Larkin, playful and spritely, on the cusp of womanhood; and Eldergirl, the aged self who wanders the old building and longingly remembers the world when it was new. This is the blueprint with which the poet opens our vision. Through this tension we encounter the crux of this collection: the jarring disparity between present experience and past memory. For though we may step into the same river twice, we recall it differently than how we first experienced it. Many waters have passed since then, and many are the events that have shaped and reshaped us in the interim. Thus does Klein blur the contours of time and move the reader not merely to feel the past but to be aware of themselves and their own double consciousness as they move through it. This experience of reading can feel abrupt, even dislocating at times, but no more so than when we, like Eldergirl, come home after a long absence.

Klein’s poetic powers are at her zenith when she folds narrative into lyrical constructions. “Eldergirl, Between Tables,” for example, begins with a dining room antique as a touchpoint and then reaches across time to imagine how table fellowship might have been experienced by other historical figures. Love personified becomes the unlooked-for host who “[pulls] out / another chair, easing what seethes / among and within us. Bid us / enter the dear, collective Amen.” Even more poignantly, “Operation Spygirl” presents a perilous but ultimately touching picture of a pain-ridden father taking care of Larkin’s helpless mother after surgery. Fearful that such distances between them might lead to divorce, the child speaker watches her parents bridge the gap with selfless love. The bat in “Vesper Bat,” a figure who makes various appearances in several poems, is wrapped in the metaphorical conceit of a priest “briefly ordained for the care of souls.” Flying through the night, it “echolocates the scar, / enwrapping hurt in widening, / wordless arcs,” healing in ways that even poetry cannot serve. In Eldergirl’s vision of creation, even the oft-hated bat can not only be redeemed but can serve as God’s instrument to redeem others.

As Fowler House sits beside a lake, it is no surprise that water plays a prominent role in this volume from beginning to end, from its primeval foundations to its therapeutic revisiting. In one of the opening pieces, “Everything begins in water,” the speaker takes us to the lake, seeing it not just as a geographical marker near the ancestral home but as an ancestral vehicle for transporting life and souls. We move with her in memory, “Beyond this shore, / out where the light cascades / sheer and true.” Not all of these works are so hopeful. “Dam,” which seems, to me, one of the darkest of these poems in its subtext and undertones, finds her favorite Uncle Dunkel escorting Larkin across the water and losing control of the boat. But all is not lost, as in “Eldergirl Wakes, to Frost,” where she reminds us “all that was liquid, in the beginning, / resurfaces somewhere: / the rivers of Eden, the tears of Christ.” As noted, there is a prominent theme of redemption throughout the volume, where God can be seen working even in the shadows.

But redemption must come through suffering. All houses possess secrets absorbed into the walls and floorboards of time, and this House is no exception. Its most troubling whispers surround Uncle Dunkel, a silent casualty of the Korean War, who returns physically sound but mentally unwell. He haunts the home as an extra family member, performing odd jobs and taking Larkin out into nature. Each remembrance of Uncle Dunkel is tinged with love and sadness as she ponders what he must be thinking in response to every sudden sound. For instance, in “Boatman,” she asks if his schizophrenia hears the rush of the dam water as simply white noise or as the advance of the enemy. What is it like to be “a man,” she asks, “alone, enduring the tenacious roar”? In another work, Eldergirl sits in the kitchen, imagining what it might have been like for Dunkel’s fiancé to receive his breakup letter, wondering if his cruelty was an intentional kindness sparing her years of caring for a lunatic. In several poems, the poet contemplates a piece of barbed wire, and the twisted purpose it plays as both plot device and symbol. As part of the volume’s interest in subjectivity, the fourth wall dividing the fractured psyche of the speaker and the external impressionism of the audience is a thin membrane, and we are invited not only to watch but to create, to discover truth and to determine it for ourselves.

Hawthorne’s house with its seven gables causes the visitor to feel small, in awe at the grandeur and ineffable construction of the edifice. So, too, feels the reader of The House of 49 Doors. Much deeper are its recesses than can be explored in this review. The reader may open the book asking questions of the literal and figurative: Does the house truly have 49 doors? Or are they merely imaginative fixtures in a mental landscape? Is this history Klein depicts real? Or is it only the disjointed fragments of a half-remembered past? Perhaps such questions are irrelevant, as either way we are vicariously invited to experience its wraiths and shadows of life experienced and life remembered. And in the life of poetry do we see mirrored our own.

'Book Review: “House of 49 Doors”' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!