In part 1 of this article, we saw a brief history of the Matthew Bible, first published in 1537. It was the work of three Englishmen living in Antwerp: William Tyndale, who translated the New Testament and the first half of the Old from the Hebrew and Greek; Myles Coverdale, who translated the other Scriptures and the Apocryphal books, working mainly from the German Bibles that were newly available; and John Rogers, who compiled their work and oversaw printing and production.

The 1537 Matthew Bible is a uniquely Anglican Bible and proceeds of a sweet catholicity. It demonstrates what historian George Park Fisher called “that reverence for antiquity and the ‘Primitive Church,’ that interest in the fathers, and deference to patristic teaching, which had belonged to the English Reformation from the outset.”((George Park Fisher, History of Christian Doctrine (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1909), 355.)) In his commentaries, Rogers often referred to the teaching of the Church Fathers. He even went out of his way to defend the perpetual virginity of Mary.((Roger’s note on Matthew 1:25 says Jesus was called Mary’s first son “not because she had any after, but because she had none before.”)) His polemical notes were milder and fewer in number than has been falsely alleged (no more than a handful), and for the most part were confirmed in the Articles of Religion, such as those that argued against purgatory or defended salvation by grace alone.

The Matthew Bible contained the Church Calendar along with an Almanac to calculate the dates of moveable feasts for the years 1538-57. Rogers, as Coverdale and Tyndale had also done, simply assumed that life would be organized around the Calendar, as it had been for centuries. At the back of the volume was a “Table … Wherein ye shall find the Epistles and the Gospels after the use of Salisbury.” These features of the Matthew Bible, together with its calm though not dogmatic acceptance of episcopacy and the general tenor of its teaching, fit it well for the Church that Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell were attempting to build when the Mathew Bible first arrived in England.

But not everyone appreciated it. Like any good Anglican, the Matthew Bible found itself caught between the Roman Catholics and the Puritans.

The Roman Catholics objected to the notes

The Roman Catholics especially resented Rogers’ Protestant notes and commentaries. To appease them, Cromwell commissioned Coverdale as chief editor to work on a new Bible. The Matthew Scriptures were chosen as the base for a minor revision. Coverdale got to work with his usual dispatch, and in 1539 we received the Great Bible, which became the official version of the young CofE.

Although the Great Bible retained many or most of John Rogers’ chapter summaries, it contained no marginal notes.((I have not examined every page, but where I checked in my facsimile of the 1540 Great Bible I found that, except for the Psalms, Coverdale kept Rogers’ chapter summaries. These are a commentary of sorts.)) Coverdale would have liked to include some, but it was thought best to avoid occasion for controversy. However, as time would tell, this left a vacuum that the early Puritans, hostile to the CofE, were swift to fill with their controversial commentaries in the Geneva Bible. In fact, the unrest caused by their teachings, and their war against “Romish” and “idolatrous” traditions, were behind Queen Elizabeth’s decision to commission the Bishops’ Bible and, later, King James’ version. They each hoped to displace the troublesome Geneva Bible and diminish its influence.

The early Puritans

A note on terminology: when I use the term “Puritans” for the authors of the Geneva Bible, I mean it in its classic, original sense. It refers to those zealous men who felt called to “purify” the Church and restore it to its “true” state. They began with attacks on externals – vestment, ceremony, images, and so forth – but soon took aim at the CofE Prayer Book, governance, and Calendar. This was inextricably tied in with their postmillennial doctrine and their mission to grow the Church in power and glory.((See Nick Schoeneberger, “The Biblical Case for Puritan Postmillennialism,” for a brief summary of their doctrine: https://purelypresbyterian.com/2015/12/12/the-biblical-case-for-puritan-postmillennialism. Accessed May 2, 2018.))

The Oxford English Dictionary records the first written use of the term ‘Puritan’ in 1565,((Oxford English Dictionary online, s.v. ‘Puritan.’ The quotation: “1565 T. Stapleton Fortresse of Faith f. 134v ‘We know to weare in the church holy vestements, and to be apparailled priestlike semeth..absurde to the Puritans off our countre, to the zelous gospellers of Geneva.’” Accessed March 20, 2018.)) but it was certainly in use before that time. A nascent Puritan spirit was manifest as early as the 1540s in London, but grew in Geneva in the 1550s when the Protestants went into exile during the Marian persecutions. There can be no question about the Puritanism of the authors of the Geneva Bible. Condemnation of ceremony is frequent in their notes, and the groundwork is laid for a Presbyterian form of Church government, postmillennialism, and the rest of the Puritan platform. They may also be considered Calvinists because they were followers of John Calvin, and I have seen his influence in their commentaries. But it is as yet unclear to me (and not necessary to understand for my purpose here) the extent to which Calvin may have influenced their extremism. He died in 1564, so was certainly alive when they published, but it may be that they were more radical than he.

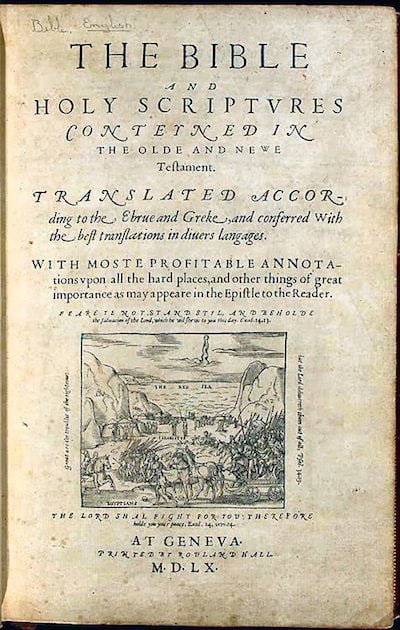

In any event, the complete Geneva Bible was published in 1560. There is no doubt in my mind that the major reason for its publication was to advance the Puritan cause. It was intended to assist in cleansing, restoring, and making converts for the “True Church.” Had the conservatives foreseen the difficulties it would cause, they might rather have tolerated Matthew’s version than suppressed it. It could have checked the Puritan influence. Rogers’ rare Zwinglian comments on the Sacraments((Rogers wrote in the Table of Principal Matters: “Baptym [sic] bringeth not grace with it / as appeareth by Symon the soth-sayer. Act.viii.d.” Such a comment would alienate both friends and foes of the Reformation. He took this from Pierre Olivetan’s 1535 French Bible.)) amount to nothing in comparison to the invective in the Geneva Bible. (Indeed, they can be of no real moment, since no man’s words can make or break the Sacraments; it is the word of the Lord that makes them.) But the Geneva commentaries chopped at the foundations.

The Geneva Bible attack on “outward things”

Ceremonies were an especial target of the Geneva notes. I did a computer search of the Psalms in the 1599 version and found notes to the effect that ceremonies are impure (note on Psalm 4:5), and do not belong in New Testament worship any more than candles or “lights” (33:2). They are nothing in respect of real spiritual service (40:6). Numerous comments disdain ceremonies and traditions as “outward” and hypocritical things. They stress that ceremonies were appointed for a time under the law, but under the gospel have been abolished (81:1, 138:2).

The Matthew Bible, on the other hand, accepts ceremonies without question. True, the Matthew men were concerned that ceremonies be rightly regarded and not abused: they must be meaningful and not overdone. But Tyndale expressly approved of ceremonies in the Church because, as he put it, they “preach” Christ visually, in a way that words cannot.((See for example William Tyndale, An Answer to Sir Thomas More’s Dialogue, ed. Henry Walter, Cambridge: Parker Society, 1850 (facsimile; Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 2006), 59-60 and 97.)) See Rogers’ simple acceptance of a Lenten tradition arising from the tearing of the temple veil when Jesus died:

Matthew Bible note upon Mark 15:37: This veil that tore in two pieces was a certain cloth that hung in the temple dividing the most holy place from the rest of the temple, as our cloth that is hung up during Lent divides the altar from the rest of the church. The tearing of this veil signified that the shadows of Moses’ law were to vanish away at the flourishing light of the gospel.

But consider how this vitriol in the Geneva Bible might have affected the people:

Geneva Bible summary of Psalm 50: Because the Church is always full of hypocrites which do imagine that God will be worshipped with outward ceremonies only without the heart: and especially the Jews were of this opinion, because of their figures and ceremonies of the Law, thinking that their sacrifices were sufficient. Therefore the Prophet doth reprove this gross error, and pronounceth the Name of God to be blasphemed where holiness is set in ceremonies. For he declareth the worship of God to be spiritual, whereof are two principal parts, invocation and thanksgiving.

By way of contrast, below is what Rogers wrote on this Psalm. He does not overlook the prophet’s condemnation of false self-righteousness, but note the difference in tone and emphasis. See also how he saw a promise of the gospel that was missing from the Geneva version:

Matthew Bible summary of Psalm 50: He prophesieth that God will call all nations of the earth unto him by the Gospel: And that he will require the confession and praising of his name, and not sacrifice. And how greatly he will abhor them which boast themselves to be religious and holy, and are in deed nothing less [no such thing].

Many Geneva notes also insist that musical instruments have no place in the Church. On Psalm 92:3, which calls for praise with harp and strings, there is a note, “These instruments were then permitted, but at Christ’s coming abolished.” At Psalm 150:3, which calls for praise with trumpet, viol, and harp, the note says, “Exhorting the people only to rejoice in praising God, he maketh mention of those instruments which by God’s commandment were appointed in the old Law, but under Christ the use thereof is abolished in the Church.” This teaching inflamed superstitious fears, and people began to attack and damage church organs. Irony reigned supreme during the Puritan Interregnum, when ordinances were made requiring organs to be destroyed as “Monuments of Idolatry and Superstition.”((A resistance to music in the Church was fomenting before the 1560 Geneva Bible was published, but in the 1570s it took off. It is difficult to imagine that the Geneva Bible did not contribute to the trouble. See http://soundsmedieval.org/library/130302-removal-of-organs-from-churches.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2018.))

However, music was never an issue in the Matthew Bible.

Puritan attacks on priests

The Puritans demonized anything that smacked of Rome, including the priestly office. Consider the 1560 commentary on Revelation 16:2, the noisome botch that fell upon people who had the mark of the beast:

1560 Geneva Bible note on Revelation 16:2 This was like the sixth plague of Egypt, which was sores and boils or pocks: and this reigneth commonly among Canons, monks, friars, nuns, priests, and such filthy vermin which bear the mark of the beast. [Note removed in 1599]

How might this have poisoned people against their priests? Rogers never indulged in such invective. True, he had a note protesting abuses of clerical office, but that is quite a different thing and should offend no sincere person:

Matthew Bible note on 1 Timothy 3:1, as updated in the October Testament: A bishop is as much as to say one who sees to things, who watches over: an overseer. When he desires to feed Christ’s flock with the food of health – that is, with his holy word, as the bishops did in Paul’s time – he desires a good work and the very office of a bishop. But he who desires honour, looks for personal advantage, is greedy for great revenues; who seeks preeminence, pomp, dominion; who wants more than enough of everything, rest and his heart’s ease, castles, parks, lordships, earldoms, etc. – such a man does not desire to work, much less to do good work, and is anything but a bishop as Saint Paul here understands a bishop.

Rogers’ note accepts Anglican polity. The objection against covetous clergy simply reflects the state of affairs at the start of the Reformation and is reasonable.

Therefore, Matthew’s Version might have served as a soft foil against the Puritan influence. But the Roman Catholics wanted none of it, and so it was replaced by the Great Bible. This appeared to satisfy the conservatives, but not so the Puritans.

Puritan attacks on the Scriptures

Moderns often assume the Geneva Bible was a close cousin to Matthew’s version, but nothing could be further from the truth. Its eschatology, ecclesiology, and much more, departed far from the beliefs of the Matthew men (and early Reformers such as Martin Luther). It taught a different form of “Protestantism.” Furthermore, it is also widely assumed nowadays that the Puritans were superior scholars, and that they improved and corrected Tyndale and Coverdale’s translations. Indeed, this is what they told us. This is what they wanted us to believe.

The Puritans entered onto the field after the battle was over and English Scriptures were established in the Church. They took up the soldiers’ work and claimed they could do a better job because they had superior knowledge of the biblical languages and a new revelation of “clear light” from God. Though Coverdale and Tyndale were of the same generation, and Coverdale was in fact still living, the Geneva revisers characterized their work as immature, or from “the infancy of those times.” In their 1560 preface they demeaned the original translations, saying they “required greatly to be perused and reformed” – that is, they must be reviewed and corrected by the Puritans:

Preface, 1560 Geneva Bible: We thought that we should bestow our labours and study in nothing which could be more acceptable to God and conformable to his Church than in the translating of the Holy Scriptures into our native tongue; the which thing, albeit that divers heretofore have endeavoured to achieve [i.e. Tyndale and Coverdale], yet considering the infancy of those times and imperfect knowledge of the tongues, in respect of this ripe age and clear light which God hath now revealed, the translations required greatly to be perused and reformed.((Preface to the 1560 Geneva Bible. (Reproduced in 1599 Geneva Bible, modern spelling Tolle Lege edition, beginning at p. xxvii.) Later in their preface they also demeaned Tyndale and Coverdale’s translations as “irreverent.” This is also discussed in The Story.))

Here are two justifications for “reforming” the original translations. One is their alleged infancy and imperfection. What temerity. Space does not allow for discussion of this,((The Puritans adopted an eccentric model of literalism , which I hope to examine in Part 2 of The Story of the Matthew Bible. They claimed this was more “reverent.”)) but I do not doubt that the real problem was that the existing Bibles did not assist the Puritans, and so they needed to find fault. They also needed to establish themselves as biblical authorities. And so they took in hand first Tyndale’s New Testament, and then the Old Testament of the Great Bible,((As to the Geneva sources, see S. L. Greenslade, “English Versions of the Bible,” The Cambridge History of the Bible, Vol. 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1963), 156-57; see also F. F. Bruce, The English Bible, A History of Translations (New York: Oxford University Press, 1961), 86, and Daniell, Bible in English, 284, 296. The Puritans published their revised New Testament in 1557, and a further revision of it along with the rest of the Scriptures and the Apocrypha in 1560.)) and “perused and reformed” them. On top of that, they added copious commentaries promulgating their doctrine.

To return one last time to the issue of ceremonies, and to illustrate how thoroughly the Puritans remade the Bible, observe how they took care even with page headers. Earlier Bible headers made generous mention of “Ceremonies” in the book of Leviticus, but the 1560 Geneva avoided this:

Page headers in the book of Leviticus:

| Bible version | ‘Ceremonies’ | ‘Sacrifices’ | Other or blank |

| 1535 Olivetan | 17 | 0 | 4 |

| 1537 & 1549 Matthew Bible | 23 | 0 | 2 |

| 1540 Great Bible | 15 | 2 | 8 |

| 1560 Geneva Bible | 5 | 8 | 15 |

The Puritan “light”

The second reason the Puritans gave for making their Bible was that they had received a revelation of “clear light” from God. And what was this light? They do not say, but the massive number of commentaries relating to prophecies of the Church – a theme that is nowhere to be found in the Matthew Bible, but which is everywhere in the Geneva version – tells me their new light was their postmillennial doctrine of the Church. This also explains why they went against Tyndale in the controversy about the translation of ‘ecclesia,’ and rendered it ‘Church’ instead of ‘congregation’ – thus ironically taking the Roman Catholic side.

Closely bound up with all this was the Puritan conviction that they were the prophets, “reformed” Protestants, who would restore the Church. With the sword of their mouth (and whatever else it might take((In their 1560 dedication to Queen Elizabeth, the Puritans exhorted her, by reference to Old Testament examples, even to “slay … whosever would not seek the Lord … whether he were small or great, man or woman.” Lest the Queen be reluctant to follow this counsel, they wrote, “If these zealous beginnings seem dangerous, and to breed disquietness in your dominions, yet by the story of King Asa, it is manifest that the quietness and peace of kingdoms standeth in the utter abolishing of idolatry, and in advancing of true religion.”))), they would destroy Antichrist; that is, the papacy. This the Reformation had failed to accomplish, but they would do it, and in a future millennium the True Church would be perfected.((Schoeneberger, “Puritan Postmillennialism.”)) They saw such prophecies everywhere in the Old Testament. Where Rogers saw Christ triumphant, they saw their Church triumphant – or at least, like any good Roman Catholic, could scarcely see Christ without their Church.((There are related issues in the Geneva Bible, also apparently the fruit of postmillennialism. One is that New Covenant promises are sometimes associated with the Lord’s second coming, not his first. Also, the “kingdom of Christ” refers not to his reign in the hearts and conscience of his faithful people, which was the pure Protestant teaching of the early Reformation, but to his reign in the Church, which is closer to Roman Catholicism.)) Below are only two examples from among hundreds:

Chapter summaries, Isaiah 2

Matthew Bible: Of the coming and death of Christ: and of the calling of the heathen.

Geneva Bible: The Church shall be restored by Christ, and the Gentiles called. The punishment of the rebellious and obstinate.

Chapter summaries, Psalm 87

Matthew Bible: He praiseth the heavenly Jerusalem, that is, the congregation of the faithful, unto which he prophesieth that very many shall come of [from] all nations.

Geneva Bible: The holy Ghost promiseth that the condition of the Church, which was in misery after the captivity of Babylon, should be restored to great excellency. So that there should be nothing more comfortable than to be numbered among the members thereof.

To restore the New Testament Church, now in Babylonian captivity under Rome, the Puritans believed that all things “Romish” must be overthrown – and that included the young CofE with its “popish dunghill” (the Book of Common Prayer),((The 1572 Puritan Admonition to the Parliament accused the prayer book as “an unperfecte booke, culled & picked out of that popishe dunghill, the Masse booke full of all abhominations.” Walter Howard Frere and C. E. Douglas, eds., Puritan Manifestoes: A Study of the Origin of the Puritan Revolt, London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1907 (facsimile; Delhi, India: Facsimile Publisher, 2013), 16.)) its idolatrous ceremonies, and its unenlightened Bibles.

Obviously, the purpose and teaching of the Geneva version were of a very different spirit. The Matthew men intended only to give us God’s word as plainly as they could. They were fighters for truth. The Puritans, however, were fighters for the True Church. Indeed, they were like the Roman Catholics in their zeal, except that now the holy war went from “Mother Church vs. Heretic” to “True Church vs. False Church.” And their Bible was an important weapon in their arsenal.

Thus Matthew’s version (along with its close cousin, the Great Bible) was caught in the middle, authored by Detestable Heretics for the False Church. Ironically, in the end it was the new Protestants who made the greatest inroads against it.

Conclusion

The Matthew Bible is essentially an Anglican book. Though, as Myles Coverdale said, “There is no man living that can see all things, neither hath God given any man to know everything,”((“Myles Coverdale unto the Christian Reader,” prologue to his 1535 Bible, Remains of Myles Coverdale, ed. George Pearson, Cambridge: The University Press, 1846 (facsimile; LaVergne, TN, USA: BiblioLife, LLC), 14.)) Rogers’ notes were (I contend) excellent, despite a few that I question or dispute. They were of a reasonable and reverent Christian spirit following the via media. The Scriptures are rich in spiritual food, Christ-centered, amillennial, and accord with the Prayer Book creeds. Further, though the translations are older than the KJV, they are easier to understand due to their plainer style, and are also free of the Puritan influence.

Under unrelenting pressure, however, and besieged on all sides, the Matthew Bible was squeezed out. Most modern academics are under the Geneva spell. They admire the Matthew men as heroic, but accept the Puritan condemnation of their work; their mantra is, “Geneva was humming with scholarship.” Coverdale is dismissed because he did not translate directly from the biblical languages (though he certainly had some knowledge of them). Instead, he used other men’s translations as his base; that is, he used German Bibles that he trusted.((Coverdale confirmed this in his preface to his Bible. He was not ignorant of the biblical languages. After all, he had worked closely with Tyndale and also worked on the Great Bible. However, his comments indicate that he respected Tyndale and Luther as the masters of direct translation.)) The manifold irony of this, however, is that the scholars who thus dismiss Coverdale have confirmed that the Puritans also used other men’s translations as their base: they used English translations that they condemned.((See note 11. Good scholars do not take someone else’s lousy work, patch it up, and then call it their masterpiece, like the Geneva revisers did. This is inconsistent with integrity and with real scholarship. But through this device, God has preserved much of the original translations.))

In the end, God will judge the Bibles that we have received – both the first, blood-bought translations and all the revisions. In the meantime, the original Scriptures were so preserved in the King James Version that the Holy Spirit has used them mightily. When that Bible is read in the Church, we are still hearing the voices of Tyndale and Coverdale as they spoke to us in Matthew’s version almost five centuries ago.

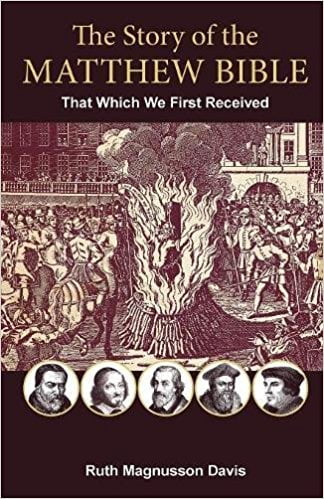

Learn the dramatic story of the blood-bought 1537 Mathew Bible, a story of courage and faith:

'The 1537 Matthew Bible: More Anglican than Not' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!