I want to bring a text to our readers’ attention that will undoubtedly seem obscure, especially to those not already familiar with the sort of domestic piety, usually done in accordance with The Book of Common Prayer, that is found among the great (and even lesser so) English houses of the seventeenth century and onward. It was a personal interest in this longstanding tradition of utilizing the set liturgies of the established Church in various private settings, and a corresponding desire for the cultivation of a good and well-ordered home that led me to discover George Wheler’s 1690 book The Protestant Monastery. Wheler’s book presents an almost ideal historical alignment for studying this constellation of related concerns. In our modern age of anxiety over the secularizing forces that threaten to loosen and break the natural and spiritual bonds of family and religious life, it may prove instructive to look back on this early example of pastoral care for domestic life. The Protestant Monastery remains remarkably contemporary for all of its heartfelt wisdom and guidance.

Before looking at Wheler’s text though, I’d like to set the cultural stage for such an odd-seeming book to our modern eyes, with the hope of showing that its appearance was rather more of an inevitability than a strange accident of history. From the religious policies of Archbishop William Laud,[1] to the “Arminian Nunnery” of the Ferrar family at Little Gidding,[2] it will seem plain that the stage was indeed set for this pastoral pamphlet to emerge. First, though, I want to draw the reader’s attention to a more recent (but relevant) work of the nineteenth century, from the parochial writings of Washington Irving in his much beloved holiday classic “Old Christmas and Bracebridge Hall”:

I had scarcely dressed myself, when a servant appeared to invite me to family prayers. He showed me the way to a small chapel in the old wing of the house, where I found the principal part of the family already assembled in a kind of gallery, furnished with cushions, hassocks, and large prayer-books; the servants were seated on benches below. The old gentleman read prayers from a desk in front of the gallery, and Master Simon acted as clerk, and made the responses; and I must do him the justice to say that he acquitted himself with great gravity and decorum.

…

I afterwards understood that early morning service was read on every Sunday and saint’s day throughout the year, either by Mr. Bracebridge or by some member of the family. It was once almost universally the case at the seats of the nobility and gentry of England, and it is much to be regretted that the custom is fallen into neglect; for the dullest observer must be sensible of the order and serenity prevalent in those households, where the occasional exercise of a beautiful form of worship in the morning gives, as it were the key-note to every temper for the day, and attunes every spirit to harmony.[3]

“Master Simon Acted As Clerk” from “Old Christmas and Bracebridge Hall”

“Master Simon Acted As Clerk” from “Old Christmas and Bracebridge Hall”

❧

Laudianism: a Continuation of “Olde England”?

Washington Irving’s account of the devotional life of the noble family at Bracebridge Hall might very easily be discounted as mere legend or exaggeration by readers of a more skeptical inclination. In the same way, his accounts of the various other “country” traditions and observances[4] might be dismissed as typical of certain romantic attitudes about an ancient, but imagined merry “Olde England” prevalent at the time.

When it comes to stories of “Olde England,” an enchanted landscape of peculiar folk traditions and revelries begins to emerge, especially surrounding such ancient observances as holy days, so that it can be difficult to separate history from myth.[5] Many of these cultural observances were abolished in the early years of the English Reformation and continued to be opposed by those of a puritan conviction, only to be permitted again under the reign of King Charles I as part of the “traditional” religious program advocated both by himself and his Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. This “Laudian” change in policy struck home for many rural Englishmen in the form of the 1633 Declaration of Sports.[6] For a time the people of the English countryside didn’t have to choose between the established Church of England and the traditional games and observances they had enjoyed from time immemorial.[7] This union between merry Olde England and the protestant Church of England was to be short-lived though. Christmas itself, along with all other holy days and associated observances and traditions would soon be outlawed under the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell, who ruled England for a time after having defeated King Charles I in civil war and then beheading both Charles and Archbishop Laud.

From “Through Merrie England” illustrated by F.D. Bedford

From “Through Merrie England” illustrated by F.D. Bedford

Eventually, both monarchy and the Church of Archbishop Laud would return to England, and with it the final and current edition of The Book of Common Prayer (1662). The same prayerbook described above by Irving in the family prayers at Bracebridge Hall, and we have good reason to believe the scene he describes is an accurate account. A scene representing a tradition of family worship tracing back to before the English Civil War, but also very much active during the war, and long after it. This kind of piety, one based on using the authorized Anglican liturgy within the home, is described by theologian Martin Thornton in his classic work, English Spirituality:

To the seventeenth, or indeed nineteenth-century layman the Prayer Book was not a shiny volume to be borrowed from a church shelf on entering and carefully replaced on leaving. It was a beloved and battered personal possession, a life-long companion and guide, to be carried from the church to kitchen, to parlor, to bedside table; equally adaptable for liturgy, personal devotion, and family prayer: the symbol of a domestic spirituality—full homely divinitie.[8]

❧

Little Gidding: the Model Anglican Household

The most famous such household of devout Prayerbook worship was that of Nicholas Ferrar, which would later be immortalized by the poet T. S. Eliot. Long before Eliot penned his Four Quartets though, the house called “Little Gidding” already had a history of both controversy and hagiography, leading back to the same Laudian religious reforms already mentioned, and including a surprisingly intimate encounter with royalty during the English Civil War.[9]

St. John’s Church, Little Gidding

St. John’s Church, Little Gidding

Nicholas Ferrar was an ordained deacon in the Church of England and a prosperous merchant. He lived with his family in their stately manor house in the country, where the domestic chapel of St. John served as the center of a daily observance of Morning Prayer and Evensong according to the Anglican Prayerbook. Their piety was renown and seemed to be after the “old high-church,” religious temperament promoted by Archbishop Laud and his followers of the time. The Ferrar family became widely known both by its admirers and by its critics. A Puritan tract calling them “The Arminian Nunnery”[10] was distributed during Ferrar’s life which was highly critical of the ceremonial along with the supposed arminian theology celebrated there. Among friends and admirers though, the Ferrars had no less than the poet George Herbert and King Charles I to boast of. The King was said to have visited several times, and even to have sought refuge at Little Gidding once, upon his defeat on the field of battle, during the English Civil War.[11]

❧

George Wheler: Pastoring the Domestic “Monastery”

There can be no doubt that George Wheler would have been aware of such an exemplary model of family devotional life as the Ferrar household. He may very likely have had them in mind when he first began writing his “Protestant Monastery.” Little Gidding did not stand alone however, as an example of that rich integration of devotion based on The Book of Common Prayer, and the ordinary rhythm of a busy, household life. Wheler himself states in his introductory epistle that the system he recommends in his book is one which has been used in his own home for many years now.[12] We also have record of many other domestic chapels and house oratories, some of them still preserved or in use to this day, among the various manor houses which still stand on English soil, like proud monuments to a forgotten way of life. I have personally visited and even prayed in some such examples. To the American admirer these are places of ancient charm and deep wells of cultural memory.

It seems that there was a real desire and even a demand for such a manual of instruction as George Wheler chose to produce near the very end of the seventeenth century, but Wheler’s manual seems to stand out in the degree to which he integrates the natural and practical realities and concerns of domestic life with the spiritual. His insistence on referring to such life in monastic terms too, seems unusual for the time. He certainly goes to great lengths in order to justify the use of such a term in the opening epistle, attempting to clear himself of the worst possible accusation of his time, that of being a “crypto-papist.”

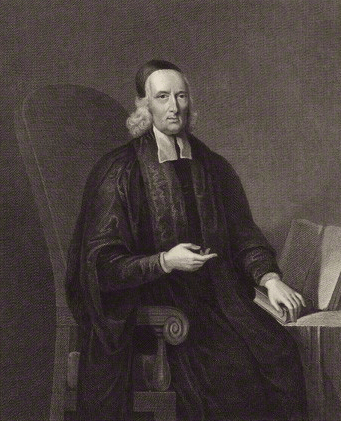

Sir. George Wheler (1651-1724)

Sir. George Wheler (1651-1724)

❧

Summary of the Text

Wheler begins his book with a short epistle to the reader, in which he explains the purpose for writing such a treatise, how the idea for it first came to him, and the beginnings of a defense and explanation for choosing to refer to the Christian home as the “protestant monastery.”

The first four chapters comprise of an extended discourse on the nature of monasticism (Of a Monastic Life in General Sacred and Profane), a historical account of it’s origins (Of the Beginning and Progress of Monasteries in the Christian Church), a defense and explanation for the dissolution of the monasteries in England (The just Censure of the Church of England: What they have done? and do allow), along with a recommendation of the benefits that might come from having vow-free convents (Of Monasteries for Women). What’s clear from this first portion of the book is that Wheler’s use of the term monastery is no mere nudge in the direction of Christain communitarianism. He has done a thorough study of Christian monasticism and has taken care to separate what is useful from the corrupt forms that he perceives to exist in the contemporary practices of the Church of Rome. Thus Wheler is prepared to recommend qualified examples of the monastic model for immediate use within a thoroughly Protestant and English context.

In the next few chapters, Wheler turns his attention to the task at hand (Of the Design of this Discourse), while he thinks a sort of Reformed monasticism would be useful to society at large his primary focus is to lift up the dignity of the domestic estate. He does so by detailing the various roles and duties of all the parties involved, the normal members of Christian households, suggesting that such ordinary vocations are every bit as God-honoring as any class of professional monks to be found in Europe.

The roles are each described in turn, beginning with the rights of the husband and father (Of Paternal Authority), but importantly, he also describes the obligations that go along with the leadership role (The Paternal Office). In the next chapter, he describes the domestic role of the wife (The Duty of the Wife), and those who are expecting to find “old-fashioned” views that denigrate the role of a woman in the traditional household may be surprised by Wheler here. Rather, this chapter opens with a remarkably fair, even contemporary-sounding evaluation of the balance between paternal and maternal power:

Next to the father or master, a wife is the first in degree, authority, and station in a family, and does in a great measure share with him in the government of it, as well as in the care; and therefore deserves the next, if not an equal share in the honor.

Wheler continues to extol the virtues and dignity of a worthy wife, but now in monastic terms:

And, as she may be enriched with virtue, and every excellent endowment, to make her husband and family happy, may better deserve the name and authority of an abbess, than any of the most richly endowed monasteries in Europe.

In the final two chapters, Wheler concludes his discussion of the well-ordered household by giving direction to children (The Duty of Children), and also to household servants (The Duty of Servants towards their Masters). Wheler may come across as old-fashioned here, but he is writing in a different time after all, and the reality is that many servants were needed to keep these old manor houses running. Which means they provided many opportunities for employment. Even so, Wheler comes across as fair-minded once again, showing genuine concern for the piety and spiritual well-being of the servants of a household and not only the family.

At this point we’ve reached the section of the book which Wheler has titled “The Application,” and it contains specific directions, prayers, hymns, and tunes to be used by a household at the various, appointed times during a typical day (following the model of the old monastic offices), and also for various occasions. Notably, one such occasion is that of a woman in labor of childbirth, for which Wheler has provided a short liturgy to be used by those present.

❧

Reflections and Further Study

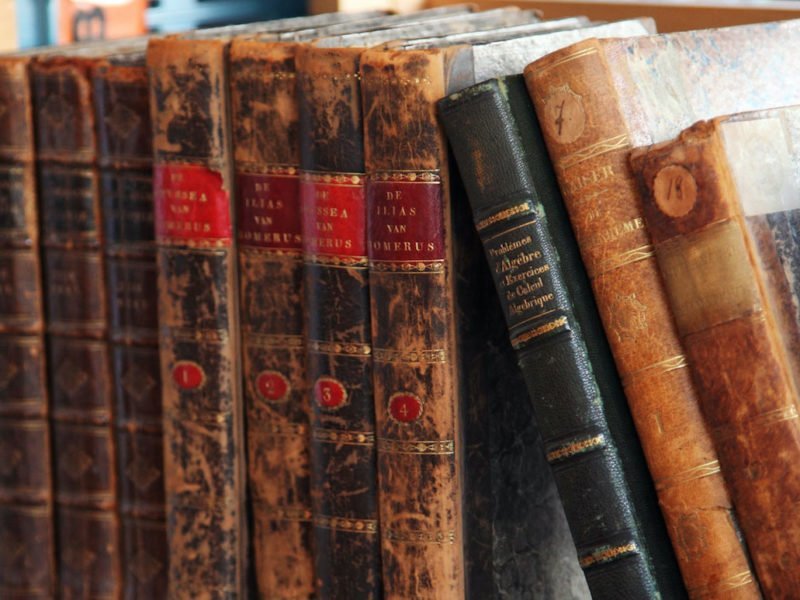

I have taken on the task of translating George Wheler’s text into a modern typeface, along with standardized capitalization, punctuation, and spelling, which has given me a greater familiarity with and appreciation for the technique and products of early modern printmaking. I can’t help but wonder when the “long S” went away, and who decided that it should? When did certain words adopt a standard spelling, and was this a gradual process? Do any of the old typefaces, like the one used in Wheler’s book, survive to this day? Which fonts are the modern inheritors of that style, and what kind of process was used to develop those? All of these questions keep cropping up in my head, as they do whenever I’m confronted by an old English text, and the charming and mysterious process by which such documents received their place in the historical record, let alone upon the library shelves of English houses.

The domestic use of the Anglican liturgy, especially The Book of Common Prayer, continues to be of interest to me. Certainly, there are other liturgies, other devotionals, and other helps and aids to prayer. Still, the fact that the same book used in the parish church for Sunday communion, and for Evensong that night in the local cathedral, also has a long history of being used under far more humble roofs, remains a compelling reality. It shows the prayerbook tradition exactly what it set out to be, it raises the common Christian layman to the level of “monk” in his own right, and it provides a method for prayer that touches every aspect of life. There’s nothing else like it in all of Christendom, and I think this makes the prayerbook an invaluable tool for the whole Church in our rootless, secular age.

Placing George Wheler’s book in the context of Laudian religious reforms, and their relation to the continuation of the traditional culture of “Olde England,” certainly paints a compelling picture of the spirit in which it was written and received. There is more research that could be done on this thesis of continuation, and I would be specifically interested in the diaries and other written records of persons belonging to the established Church. For now, I invite our readers to join me in taking up the challenge of Common Prayer in our own lives, and if it helps, to imagine our homes as “protestant monasteries” as Wheler did.

(I’m including a link to the opening epistle of Wheler’s book for your examination. I hope that it will give you a feel for the writer’s style and voice.)

Notes

- Alexandra Walsham, “The Parochial Roots of Laudianism Revisited: Catholics, Anti-Calvinists and ‘Parish Anglicans’ in Early Stuart England.” (Journal of Ecclesiastical History, vol. 49, no. 4, 1998): 620-51. ↑

- Kate Riley, “The Good Old Way Revisited: The Ferrar Family of Little Gidding c.1625-1637.” PhD diss., (University of Western Australia, 2007), 10. ↑

- Washington Irving, Old Christmas and Bracebridge Hall. (London: Macmillan and Co. and New York, 1886), 59-61. ↑

- See how the younger Bracebridge describes his father’s interest in such traditions, “He used to direct and superintend our games with the strictness that some parents do the studies of their children. He was very particular that we should play the old English games according to their original form ; and consulted old books for precedent and authority for every ‘merrie disport;’ yet I assure you there never was pedantry so delightful.” Irving, Old Christmas, 33. ↑

- See Irving, “for our men of fortune spend so much of their time in town, and fashion is carried so much into the country, that the strong rich peculiarities of ancient rural life are almost polished away.” In , Old Christmas, 29. ↑

- Walsham, “The Parochial Roots,” 628 ↑

- See Walsham, “Absorbed into the new order through apathy, inertia and the attrition of time, these conformists came to centre their religious worship on those rites and ceremonies sanctioned by the rubrics of the Book of Common Prayer which reminded them of the faith of their childhood. They insistedthat ministers wear the surplice, baptise with the sign of the cross, church women after childbirth, use wafers rather than bread when administering the eucharist and carry out funerals with fitting and old-fashioned solemnity – often hounding particularly recalcitrant vicars and curates into the local church courts.” In “The Parochial Roots,” 627. ↑

- Martin Thornton. “The Anglican Spiritual Tradition.” Akenside Press. Accessed May 4, 2019. http://akensidepress.com/2017/05/the-anglican-spiritual-tradition-part-1-of-2/ ↑

- Kate Riley, “The Good Old Ways Revisited: The Ferrar Family of Little Gidding c.1625-1637.” ↑

- Riley, “The Good Old Ways,” 10. ↑

- Riley, “The Good Old Ways,” 22. ↑

- George Wheler. The Protestant Monastery: or, Christian Oeconomics Containing Directions for the Religious Conduct of a Family. England, 1698. Accessed May 4, 2019. https://books.google.com/books?id=E3RjAAAAcAAJ&pg ↑

'George Wheler’s ‘Protestant Monastery’ and Olde England' has 1 comment

December 25, 2019 @ 7:42 pm Columba Silouan

This idea of “Protestant Monasticism” is great. Hopefully there is room in the ACNA for full-fledged Monasticism as well. Think of how strong allowing and following BOTH models might make conservative Anglicanism.